November 20, 2016 – We arrived in Loreto from Playa Santispac before lunch on November 18th, a beautiful, short and uneventful drive, the best kind. Everyone enjoyed our beach time at Playa Santipac as calm seas, warm water, sunny skies, hot temperatures and little wind made the experience as good as it gets. Interesting the new fence along the beach, 20 meters (yards) from the high tide mark. This is an official Federal Zone the sign states, no parking or driving a newly designated protected area. Rumour is the Ejido has not paid the Federal Tax due for access to the property so now they cannot let RVers camp there. This makes sense as we visited eight (8) other beaches and saw no fences in place. Oh well, everyone still liked their seaside view and beautiful sunrises.

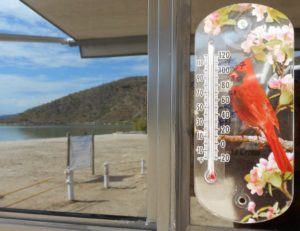

The gang spent lots of time in the water with no sting rays in sight. We also said goodbye to Larry & Linda on arrival, they were off to their digs at Playa Burro. They will be picking up on the January tour return. Larry is set to perform as the lead guitar player for the local gringo band, Fast Eddy and the Slow Learners. On Day 2 at Santispac it was hot, summer hot, well over 100F (38C), we had one (1) night of difficult sleeping. The group spent most of the daylight hours either swimming, chair floating, paddle boarding or kayaking, some folks all of the above. Bruce and Marian had collected lots of firewood for our fire, enough for two (2) fires. The Pot Luck dinner was a big hit as always, great cooks and terrific food. Some went out with a local fisherman and guide for a tour of Bahia Concepcion and to find a Whale Shark which they did find. Lots of great memories made on this beach and everyone looks forward to the return trip.

The day we headed to San Ignacio the group headed off to the Salt tour, the first tour of the season for Malarrimo. By all accounts well worth the $12 fee. On the drive from Guerrero Negro to Vizcaino Wayne & Anke bumped mirrors with another vehicle so at our body break we replaced the glass and carried on. We arrived in San Igancio late in the afternoon, made are way into the square where date pies and cakes were popular. On our return to Rice & Beans we had a big turnout for dinner and as expected the Margaritas’ were a big hit. Next day we were up early and off to the beach (Playa Santispac).

Our time in Loreto has been busy, today is a free day except for the dinner tonight at the Giggling Dolphin. First day we spent resupplying and getting water. The next day we headed up to San Javier, always my favourite drive. On our return we collected folks and went to Del Borracho for lunch. Latter in the afternoon we headed back to downtown for the Art Walk and caught a wedding to boot. We dropped by Marv & Shel’s house for a short visit and also ran into Dan & Gail who have a spot in Loreto Shores and much to our surprise, Afrain, Vivianne and their daughter (from the Blanket Factory in Pescadero). I also dropped into Kathy’s shop, Gecko’s Curios, and had a good chin wag.

Today is Revolution Day, we are looking for a Parade on the main drag.

Did you know? – Porfirio Part 1

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori (Spanish pronunciation: [porˈfiɾjo ði.as]; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915) was a Mexican soldier and politician, former president who served seven terms as President of Mexico; a total of three and a half decades from 1876 to 1911. A veteran of the Reform War and the French intervention in Mexico, Díaz rose to the rank of General, leading republican troops against the French-imposed Emperor Maximilian. Seizing power in a coup in 1876, Díaz and his allies ruled Mexico for the next thirty-five years, a period known as the Porfiriato, the best period of industrial and economic prosperity it has known in Mexico, was the only occasion when the Mexican peso was worth one US dollar and where external debt was paid in full. Diaz resigned as president before the latent Mexican Revolution and spent his last years in Paris where the French government, with honors offered him political asylum.

Díaz is a controversial figure in Mexican history, he was seen as a villain among the revolutionaries who overthrew him, and as a hero of capitalism in Latin America in the business community. The Porfiriato was marked by corruption and bloodshed of unprecedented scale in Mexican history. Economic growth mainly benefited Díaz’ close allies such as small political groups, family and accomplices’ government posts such as heads of army units, Mexican states as well as foreigners which included the likes of the Rockefellers, Hearsts and Guggenheims of the time. Díaz in turn would require a percentage of their tax earnings, amassing a large personal fortune. His preference for heavy investment in mining and railways from American and British business follow the same purpose of corruption.

However, Díaz’s regime grew unpopular due to civil repression and political stagnation. His economic policies furthermore helped a few wealthy estate owning hacendados acquire huge areas of land, leaving rural campesinos unable to make a living; thus creating the most repressive and longest institutionalized regime ever to plague Latin America with subsistence wages for the Mexican peasantry. The main result was the institutionalized slavery system and corruption that marked the country for decades. This directly precipitated the Mexican Revolution, in which Díaz fell from power after he imprisoned his electoral rival and declared himself the winner of an eighth term in office. Díaz fled to France, where he died in exile four years later. He is buried in Montparnasse cemetery in Paris.

Early years

Porfirio Díaz was the sixth of seven children, baptized on 15 September 1830, in Oaxaca, Mexico, but his actual date of birth is unknown. September 15 is an important date in Mexican history, the eve of the date hero of independence Miguel Hidalgo issued his call for independence in 1810; when Díaz became president, the independence anniversary was commemorated on September 15 rather than the 16th, a practice that continues to the present era. Díaz was a castizo (mostly european with some indigenous). His mother, Petrona Mori (or Mory) was the daughter of a man whose father had immigrated from Spain and Tecla Cortés, an indigenous woman; Díaz’s father was a Criollo. There is confusion about his father’s name, which is listed on the baptismal certificate as José de la Cruz Díaz, but is also known as José Faustino Díaz, who was a modest innkeeper and died of cholera when his son was three. Despite the family’s difficult circumstances following Díaz’s father’s death in 1833, Díaz was sent to school at age 6. In the early independence period, the choice of professions was narrow: lawyer, priest, physician, military.

The Díaz family was devoutly religious, and Díaz began training for the priesthood at the age of fifteen when his mother, María Petrona Mori Cortés, sent him to the Colegio Seminario Conciliar de Oaxaca. He was offered a post as a priest in 1846, but important national events intervened. Seminary students volunteered as soldiers to repel the U.S. invasion during the Mexican–American War. Despite not seeing action, Díaz decided his future was in the military, not the priesthood. Also in 1846, Díaz came into contact with a leading Oaxaca liberal, Marcos Pérez, who taught at the secular Institute of Arts and Sciences in Oaxaca. Another student there was had been Benito Juárez, who became governor of Oaxaca in 1847. Díaz met Juárez that year. In 1849, over family objections Díaz abandoned his ecclesiastical career and entered the Instituto de Ciencias and studied law. When Antonio López de Santa Anna returned to power via coup d’état in 1853, he suspended the 1824 constitution and persecuted liberals. At this point, Díaz had aligned himself with radical liberals (rojos), such as Benito Juárez. Juárez was forced into exile in New Orleans; Díaz supported the liberal Plan de Ayutla that called for the ouster of Santa Anna. Díaz evaded an arrest warrant and fled to the mountains of northern Oaxaca, where he joined the rebellion of Juan Álvarez. In 1855, Díaz joined a band of liberal guerrillas who were fighting Santa Anna’s government. After the ousting and exile of Santa Anna, Díaz was rewarded with a post in Ixtlán, Oaxaca that gave him valuable practical experience as an administrator.

Life as a military man and path to the presidency

Díaz’s military career is most noted for his service in the Reform War and the struggle against the French. By the time of the Battle of Puebla (5 May 1862), Mexico’s great victory over the French when they first invaded, General Díaz had become the general in charge of an infantry brigade. During the Battle of Puebla, his brigade was placed in the center between the forts of Loreto and Guadalupe. From there, he successfully repelled a French infantry attack that was sent as a diversion to distract the Mexican commanders’ attention from the forts that were the main target of the French army. In violation of the orders of General Ignacio Zaragoza, General Díaz and his unit fought off a larger French force and then chased after them. Despite Díaz’s inability to share control, General Zaragoza commended the actions of General Díaz during the battle as “brave and notable”.

In 1863, Díaz was captured by the French Army. He escaped and was offered by President Benito Juárez the positions of secretary of defense or army commander in chief. He declined both, but took an appointment as commander of the Central Army. That same year, he was promoted to the position of Division General. Colonel Porfirio Díaz, 1861. At this time, Díaz was a Federal Deputy and had participated in two wars, namely the Revolution of Ayutla (1854–55) and the War of the Reform (1857–1861). In 1864, the conservatives supporting Emperor Maximilian asked him to join the Imperial cause. Díaz declined the offer. In 1865, he was captured by the Imperial forces in Oaxaca. He escaped and fought the battles of Tehuitzingo, Piaxtla, Tulcingo and Comitlipa.

In 1866, Díaz formally declared loyalty. That same year, he earned victories in Nochixtlán, Miahuatlán, and La Carbonera, and once again captured Oaxaca. He was then promoted to general. Also in 1866, Marshal Bazaine, commander of the Imperial forces, offered to surrender Mexico City to Díaz if he withdrew support of Juárez. Díaz declined the offer. In 1867, Emperor Maximilian offered Díaz the command of the army and the imperial rendition to the liberal cause. Díaz refused both. Finally, on 2 April 1867, he went on to win the final battle for Puebla. Five days later, Díaz married Delfina Ortega Díaz (1845–1880), the daughter of his sister Manuela Josefa Díaz Mori (1824–1856). Díaz and his niece would have seven children, but Delfina died due to complications of her seventh delivery.

When Juárez became the president of Mexico in 1868 and began to restore peace, Díaz resigned his military command and went home to Oaxaca. However, it did not take long before the energetic Díaz became unhappy with the Juárez administration. In 1871, Díaz led a revolt against the re-election of Juárez. In March 1872, Díaz’s forces were defeated in the battle of La Bufa in Zacatecas. Following Juárez’s death on 9 July of that year, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada assumed the presidency and offered amnesty to the rebels. Díaz accepted in October and “retired” to the Hacienda de la Candelaria in Tlacotalpan, Veracruz. However, he remained very popular among the people of Mexico.

In 1874, he was elected to Congress from Veracruz. That year, Lerdo de Tejada’s government faced civil and military unrest, and offered Díaz the position of ambassador to Germany, which he refused. In 1875, Díaz traveled to New Orleans and Brownsville, Texas to plan a rebellion, which was launched in Ojitlan, Oaxaca, on 10 January 1876 as the “Plan de Tuxtepec”. Díaz continued to be an outspoken citizen and led a second revolt against Lerdo de Tejada in 1876. This attempt also failed and Díaz fled to the United States of America. His fight, however, was far from over. Several months later, in November 1876, Díaz returned to Mexico and fought the Battle of Tecoac, where he defeated the government forces once and for all (on 16 November). Finally, on 12 May 1877, Díaz was elected president of Mexico for the first time. His campaign of “no re-election”, however, came to define his control over the state for more than thirty years.

Although the liberals had defeated the conservatives in the War of the Reform, the conservatives had been powerful enough still in the early 1860s to aid the imperial project of France that put Maximilian Habsburg as emperor of Mexico. With the fall of Maximilian, Mexican conservatives were cast as collaborators with foreign imperialists. With the return of the liberals under Benito Juárez, and following his death, liberals held power, but basic liberal goals of democracy, rule of law, and economic development were not reached. Díaz saw his task in his term as president to create internal order so that economic development could be possible. As a military hero and astute politician, Díaz’s eventual successful establishment of that peace (Pax Porfiriana) became “one of [Díaz’s] principal achievements, and it became the main justification for successive re-elections after 1884.”

During his first term in office, Díaz developed a pragmatic and personalist approach to solve political conflicts. Although a political liberal who had stood with radical liberals in Oaxaca (rojos), he was not a liberal ideologue, preferring pragmatic approaches to issues. He was explicit about his pragmatism. He maintained control through generous patronage to political allies. Although he was an authoritarian ruler, he maintained the structure of elections, so that there was the façade of liberal democracy. His administration became famous for their suppression of civil society and public revolts. One of the catch phrases of his later terms in office was the choice between “pan o palo”, (“bread or the bludgeon”) – that is, “benevolence or repression.” To secure U.S. government recognition of the Díaz regime, which had come to power by coup despite the later niceties of an election after Lerdo went into exile, Mexico paid $300,000 to settle claims by the U.S. In 1878, the U.S. government recognized the Díaz regime and former U.S. president and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant visited Mexico. Díaz initially served only one term—having staunchly stood against Lerdo’s re-election policy. Instead of running for a second term, he handpicked his successor, Manuel González, one of his trustworthy companions. This side-step maneuver, however, did not mean that Díaz was stepping down from his powerful position. The four-year period that followed was marked by corruption and official incompetence, so that when Díaz stepped up in the election of 1884, he was welcomed by his people with open arms. More importantly, very few people remembered his “No re-election” slogan that defined his previous campaign. During this period the Mexican underground political newspapers spread the new ironic slogan for the Porfirian times, based on the slogan “Sufragio Efectivo, No Reelección” and changed it to “Sufragio Efectivo No, Reelección”. In any case, Díaz had the constitution amended, first to allow two terms in office, and then to remove all restrictions on re-election.

Political career

Having created a band of military brothers, Díaz went on to construct a broad coalition. He was a cunning politician and knew very well how to manipulate people to his advantage. Over the next twenty-six years as president, Díaz created a systematic and methodical regime with a staunch military mindset. His first goal was to establish peace throughout Mexico. According to the late UCLA Spanish professor John A. Crow, Díaz “set out to establish a good strong paz porfiriana, or Porfirian peace, of such scope and firmness that it would redeem the country in the eyes of the world for its sixty-five years of revolution and anarchy.” His second goal was outlined in his motto – “little of politics and plenty of administration.” In reality, he started a Mexican revolution; however, his fight for profits, control, and progress kept his people in a constant state of uncertainty. Díaz managed to dissolve all local authorities and all aspects of federalism that once existed. Not long after he became president, the leaders of Mexico were answering directly to him. Those who held high positions of power, such as members of the legislature, were almost entirely his closest and most loyal friends. In his quest for even more political control, Díaz suppressed the media and controlled the court system.

In order to secure his power, Díaz engaged in various forms of co-optation and coercion. He played his people like a board game – catering to the private desires of different interest groups and playing off one interest against another. In order to satisfy any competing forces, such as the Mestizos and wealthier indigenous people, he gave them political positions of power that they could not refuse. He did the same thing with the elite Creole society by not interfering with their wealth and haciendas. Covering both pro and anti-clerical elements, Díaz was both the head of the Freemasons in Mexico and an important advisor to the Catholic bishops. Díaz proved to be a different kind of Liberal than those of the past. He neither assaulted the Church (like most liberals) nor protected the Church. As for the Native American population, who were historically repressed, they were almost completely depoliticized; neither put on a pedestal as the core of Mexican society nor suppressed, and were largely left to advance via their own means. In giving different groups with potential power a taste of what they wanted, Díaz created the illusion of democracy and quelled almost all competing forces. Díaz knew that it was crucial for him to suppress banditry; he expanded the guardias rurales (countryside police), although it guarded chiefly only transport routes to major cities. Díaz thus worked to enhance his control over the military and the police. From 1892 onwards, Díaz’s perennial opponent was the eccentric Nicolás Zúñiga y Miranda, who lost every election but always claimed fraud and considered himself to be the legitimately elected president of Mexico.

Where is Richard & Dale?