January 15, 2016 – Our 1st attempt driving to Veracruz, lead by Bruce & Marian, was unsuccessful as shortly after our departure we came to halt and a 5 hour lineup because of protest blockade. The locals were protesting the state of the road, Highway 180 north to Tampico, we are definitely in solidarity with them as we had recently driven it. The group took everything in stride, before you knew it vendors arrived, we did some shopping in the village of Casitas and Roland entertained some the locals roadside. We met a local performer (they hang by their feet and fly around a pole) and a young bus driver, good conversation on many Mexican topics. Once the logjam started to move about 1pm we returned to Sun Beach Campground to the avoid chaos when protest over.

Turns out we were now back on schedule and the next day before 8am we continued south bound. The road was good to ok from Costa Esmeralda to Boca Del Rio (south of Veracruz). It is always interesting driving thru villages, we purchased Oranges, Crayfish and Tamales. The group found a spot to pull over and I jumped in Rafael & Eileen’s RV to scout out Rancho La Condesa in Church’s book. We decided to stay here at $200 pesos per night, partial services, close to town and well-kept grounds on the river with peacocks and iguanas in the trees. After getting settled we headed out for supplies at Chedraui, next to the Liverpool, what a store and mall.

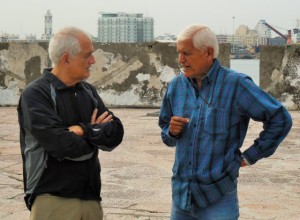

Mike & Kelly had arranged a group tour in Veracruz, we met at Hilton in Boca del Rio. We had an extensive tour of Fort San Jaun de Ulua by a very knowledgeable and stopped at the “El Gran Café de la Parraquoia” for coffee and lunch. Back at the campground Roland gave everyone a lesson on how to prepare and eat crawdads, lots of fun and tasty too. We returned into town on the 2nd day to see more of historic Veracruz, dropped the gang off at the square (Plaza de las Armas), adjacent to the Municipal Palace, Virgen de la Asuncion Cathedral. Fortunately I was able to park nearby on the street by using 2 meters, 6 pesos for 2 hours, very inexpensive for sure. During out walkabout Lisa and I were caught on the Google Street View Car, 2nd time for Lisa.

Returned to Rancho La Condesa just after lunch and headed back out in search of fresh potable water. Only a few blocks away we found a couple of roadside “aqua purificada” stands, 10 pesos for 20 liters, 5 pesos for 10 liters and1 pesos for 1 liter. On return the sun had really come out so many were reading or having a siesta. Later some of the group headed back into town for dancing in the historic Zocalo.

This morning we continued our southward journey Catemaco, lead by Mike & Kelly. Catemeco is a tourist destination with its main attractions being the lake, remnants of the region’s rainforest and a tradition of sorcery/witchcraft that has its roots in the pre-Hispanic period and mostly practiced by men. We arrived at our destination before lunch and settled the RVs into the Tetpeteoan RV Park, very nice with all the amenities and very reasonably priced at $250 pesos per night. 1st order of business was to find a lavandaria to take care of the dirty laundry. We found Juanita’s, 16 pesos per kilo and they would deliver it to the park before we left, who could beat that eh?

Tomorrow we explore what Catemaco has to offer.

Did you know?

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (Spanish pronunciation: [anˈtonjo ˈlopes ðe sant(a)ˈana]; 24 February 1794 – 21 June 1876), often known as Santa Anna or López de Santa Anna and sometimes called “the Napoleon of the West”, was a Mexican politician and general who greatly influenced early Mexican politics and government. Santa Anna first opposed the movement for Mexican independence from Spain, but then fought in support of it. Though not the first caudillo (military leader) of modern Mexico, he was among the earliest.

Santa Anna had great power in the independent country; he served as general and president several times during a turbulent 40-year career, including eleven non-consecutive presidential terms over a period of 22 years. A wealthy landowner, he built a firm political base in the major port city of Veracruz. He was perceived as a hero by his troops; he sought glory for himself and his army, and repeatedly rebuilt it after major losses. A skillful soldier and cunning politician, he dominated Mexican history of that era to such an extent that historians often refer to it as the “Age of Santa Anna.”

However, historians also rank him as perhaps the principal inhabitant even today of Mexico’s pantheon of “those who failed the nation.” His centralist rhetoric and military failures resulted in Mexico losing just over half its territory, beginning with the Texas Revolution of 1836, and culminating with the Mexican Cession of 1848 following its defeat by the United States in the Mexican-American War.

Early years

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón was born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Nueva España (New Spain), on 24 February 1794. He and his family came from a respected Spanish colonial family; he and his parents, Antonio López de Santa Anna and Manuela Pérez de Lebrón, belonged to the criollo high class (criollos were persons of primarily European descent and born in the Americas). His father served for a time as a sub-delegate for the Spanish province of Veracruz. Santa Anna’s parents were wealthy enough to send their son to school. In June 1810, the 16-year-old Santa Anna joined the Fijo de Veracruz infantry regiment as a cadet against the wishes of his parents, who wanted him to pursue a career in commerce.

Military career

In 1810, the same year that Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla started Mexico’s first attempt to gain independence from Spain, Santa Anna joined the colonial Spanish Army under José Joaquín de Arredondo. He taught him much about dealing with Mexican nationalist rebels. In 1811, Santa Anna was wounded in the left hand by an arrow during the campaign under Col. Arredondo in the town of Amoladeras, in the state of San Luis Potosí. In 1813, Santa Anna served in Texas against the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition, and at the Battle of Medina, in which he was cited for bravery. He was promoted quickly; he became a second lieutenant in February 1812 and first lieutenant before the end of that year. In the aftermath of the rebellion, the young officer witnessed Arredondo’s fierce counter-insurgency policy of mass executions.

During the next few years, in which the war for independence reached a stalemate, Santa Anna erected villages for displaced citizens near the city of Veracruz. He also pursued gambling, a vice that would follow him all through his life. In 1816, Santa Anna was promoted to captain. He conducted occasional campaigns to suppress Native Americans or to restore order after a tumult had begun. In 1821, he declared his loyalty to El Libertador (The Liberator): the future Emperor of Mexico, Agustín de Iturbide. He rose to prominence by quickly driving Spanish forces out of the vital port city of Veracruz that same year. Iturbide rewarded him with the rank of general. Santa Anna exploited his situation for personal gain. He acquired a large hacienda and at the same time continued gambling.

The era of coups

After Mexico gained independence from Spain, Santa Anna was ambivalent in support of Iturbide, who was never popular and needed the military to maintain his power. Santa Anna usually allied with his class of the wealthy and privileged, but his immediate concern was to be on the winning side in any battle. Switching allegiances never troubled him. Santa Anna declared himself retired, “unless my country needs me”.

In 1822, Santa Anna went over to the camp of military leaders supporting the plan to overthrow Iturbide. In December 1822 Santa Anna and General Guadalupe Victoria signed the Plan de Casa Mata to abolish the monarchy and transform Mexico into a republic. In May 1823, following Iturbide’s resignation, Victoria became the first president of Mexico. Santa Anna’s role in the overthrow of Iturbide gained support from other leaders, although they knew of his propensity for switching sides in an opportunistic manner. By 1824, Vicente Guerrero appointed Santa Anna as governor of the Mexican state of Yucatán. On his own initiative, Santa Anna prepared to invade Cuba, which remained under Spanish rule, but he possessed neither the funds nor sufficient support for such a venture.

In 1828, Santa Anna, Vicente Guerrero, another early leader; Lorenzo de Zavala, and other politicians staged a coup against the elected President Manuel Gómez Pedraza. He had supported the rebels as legitimate forces in the nation. On 3 December 1828, the army shelled the National Palace; the election results were annulled, and Guerrero took over as president. In 1829, Spain made a final attempt to retake Mexico, invading Tampico with a force of 2,600 soldiers. Santa Anna marched against the Barradas Expedition with a much smaller force and defeated the Spaniards, many of whom were suffering from yellow fever. The defeat of the Spanish army not only increased Santa Anna’s popularity but also consolidated the independence of the new Mexican republic. Santa Anna was declared a hero. From then on, he styled himself “The Victor of Tampico” and “The Savior of the Motherland”. His main act of self-promotion was to call himself “The Napoleon of the West.”

In a December 1829 coup, Vice-President Anastasio Bustamante rebelled against President Guerrero, had him executed, and on 1 January 1830 took over the presidency. In 1832 a rebellion started against Bustamante, which was intended to install Manuel Gómez Pedraza (who had been elected in 1828 and unseated in a coup that year.) The rebels offered the command to Gen. Santa Anna. In August 1832, Bustamante temporarily appointed Melchor Múzquiz to the post of president. He moved against the rebels and defeated them at Gallinero. Forces from Dolores Hidalgo, Guanajuato, and Puebla marched to meet the forces of Santa Anna, who were approaching the town of Puebla. After two more battles, Bustamante, Pedraza, and Santa Anna signed the Agreement of Zavaleta (21–23 December 1832) to install Pedraza as president. Bustamante went into exile. Santa Anna accompanied the new president on 3 January 1833 and joined him in the capital.

At the pinnacle of power

President Pedraza convened the Congress of Mexico, and he elected Santa Anna as president on 1 April, 1833. President Santa Anna appointed Valentín Gómez Farías as Vice-President and largely left the governing of the nation to him. Farías began to implement liberal reforms, chiefly directed at the army and the Catholic Church, which was the state religion in Mexico. Such reforms as abolishing tithing as a legal obligation, and the seizure of church property and finances, caused concern among Mexican conservatives. Farías also sought to extend these reforms to the frontier province of Alta California. Farías promoted legislation to secularize the Franciscan missions there. In 1833 he organized the Híjar-Padrés colony to bolster non-mission settlement. A secondary goal of the colony was to help defend Alta California against perceived Russian colonial ambitions from the trading post at Fort Ross.

In May 1834, Santa Anna ordered disarmament of the civic militia. He suggested to Congress that they should abolish the controversial Ley del Caso, under which the liberals’ opponents had been sent into exile. The Plan of Cuernavaca, published on 25 May 1834, called for repeal of the liberal reforms. On 12 June, Santa Anna dissolved Congress and announced his decision to adopt the Plan of Cuernavaca. Santa Anna formed a new Catholic, centralist, conservative government. In 1835 it replaced the 1824 constitution with the new constitutional document known as the “Siete Leyes” (“The Seven Laws”). Santa Anna dissolved the Congress and began centralizing power. His regime became a dictatorship backed by the military.

Several states openly rebelled against the changes: Coahuila y Tejas (the northern part of which would become the Republic of Texas), San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, Durango, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Yucatán, Jalisco, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas. Several of these states formed their own governments: the Republic of the Rio Grande, the Republic of Yucatan, and the Republic of Texas. Only the Texans defeated Santa Anna and retained their independence. Their fierce resistance was possibly fueled by reprisals Santa Anna committed against his defeated enemies. The New York Post editorialized that “had [Santa Anna] treated the vanquished with moderation and generosity, it would have been difficult if not impossible to awaken that general sympathy for the people of Texas which now impels so many adventurous and ardent spirits to throng to the aid of their brethren.”

The Zacatecan militia, the largest and best supplied of the Mexican states, led by Francisco García, was well armed with .753 caliber British ‘Brown Bess’ muskets and Baker .61 rifles. But, after two hours of combat on 12 May 1835, Santa Anna’s “Army of Operations” defeated the Zacatecan militia and took almost 3,000 prisoners. Santa Anna allowed his army to loot Zacatecas for forty-eight hours. After defeating Zacatecas, he planned to move on to Coahuila y Tejas to quell the rebellion there, which was being supported by settlers from the United States (aka Texians).

Texas Revolution

Like other states discontented with the central Mexican authorities, the Texas department of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas rebelled in late 1835 and declared itself independent on 2 March 1836. The northeastern part of the state had been settled by numerous American immigrants, beginning with Stephen Austin and his party, who had been welcomed by earlier governments. Santa Anna marched north to bring Texas back under Mexican control by a show of brute merciless force. His expedition posed challenges of manpower, logistics, supply, and strategy far beyond what he was prepared for, and it ended in disaster. To fund, organize, and equip his army he relied, as he often did, on forcing wealthy men to provide loans. He recruited hastily, sweeping up many derelicts and ex-convicts, as well as Indians who could not understand Spanish commands.

His army expected tropical weather and suffered from the cold as well as shortages of traditional foods. Stretching a supply line far longer than ever before, he lacked horses, mules, cattle, and wagons, and thus had too little food and feed. The medical facilities were minimal. Morale sank as soldiers realized there were not enough chaplains to properly bury their bodies. Regional Indians attacked military stragglers; water sources were polluted and many men sick. Because of his weak staff system, Santa Anna was oblivious to the challenges, and was totally confident that a show of force and a few massacres (as at the Alamo and Goliad) would have the rebels begging for mercy.

On 6 March 1836, at the Battle of the Alamo, Santa Anna’s forces killed 189 Texian defenders and later executed more than 342 Texian prisoners, including James Fannin at the Goliad Massacre (27 March 1836). These executions were conducted in a manner similar to the executions he witnessed of Mexican rebels in the 1810s as a young soldier. However, the defeat at the Alamo bought time for General Sam Houston and his Texas forces. During the siege of the Alamo, the Texas Navy had more time to plunder ports along the Gulf of Mexico and the Texian Army gained more weapons and ammunition. Despite Sam Houston’s lack of ability to maintain strict control of the Texian Army, they defeated Santa Anna’s much larger army at the Battle of San Jacinto on 21 April 1836. The Texans shouted, “Remember Goliad, Remember the Alamo!” The day after the battle, a small Texan force led by James Austin Sylvester captured Santa Anna. They found the general dressed in a dragoon private’s uniform and hiding in a marsh.

López de Santa Anna rode double into Sam Houston’s camp on the horse of Joel Walter Robison, a soldier in most of the revolutionary battles and later a member of the Texas House of Representatives from Fayette County. Acting Texas president David G. Burnet and López de Santa Anna signed the Treaties of Velasco, stating that “in his official character as chief of the Mexican nation, he acknowledged the full, entire, and perfect Independence of the Republic of Texas.” In exchange, Burnet and the Texas government guaranteed Santa Anna’s safety and transport to Veracruz. In Mexico City, however, a new government declared that Santa Anna was no longer president and that the treaty he made with Texas was null and void.

While captive in Texas, Joel Roberts Poinsett — U.S. minister to Mexico in 1824 — offered a harsh assessment of General Santa Anna’s situation: “Say to General Santa Anna that when I remember how ardent an advocate he was of liberty ten years ago, I have no sympathy for him now, that he has gotten what he deserves.” Santa Anna replied: “Say to Mr. Poinsett that it is very true that I threw up my cap for liberty with great ardor, and perfect sincerity, but very soon found the folly of it. A hundred years to come my people will not be fit for liberty. They do not know what it is, unenlightened as they are, and under the influence of a Catholic clergy, a despotism is the proper government for them, but there is no reason why it should not be a wise and virtuous one.”

After some time in exile in the U.S., and after meeting with U.S. president Andrew Jackson in 1837, Santa Anna was allowed to return to Mexico. He was transported aboard the USS Pioneer to retire to his hacienda in Veracruz, called Manga de Clavo. In 1838, Santa Anna had a chance for redemption from the loss of Texas. After Mexico rejected French demands for financial compensation for losses suffered by French citizens, France sent forces that landed in Veracruz in the Pastry War. The Mexican government gave Santa Anna control of the army and ordered him to defend the nation by any means necessary. He engaged the French at Veracruz. During the Mexican retreat after a failed assault, Santa Anna was hit in the left leg and hand by cannon fire. His shattered ankle required amputation of much of his leg, which he ordered buried with full military honors. Despite Mexico’s final capitulation to French demands, Santa Anna used his war service to re-enter Mexican politics as a hero. He never allowed Mexico to forget him and his sacrifice in defending the fatherland.

Santa Anna used a prosthetic cork leg; during the later Mexican-American War, it was captured and kept by American troops. The cork leg is displayed at the Illinois State Military Museum in Springfield. The Mexican government has repeatedly asked for its return. Santa Anna had a replacement leg made which is displayed at the Museo Nacional de Historia in Mexico City. A second leg, a peg, was also captured and is displayed at the home of Richard J. Oglesby in Decatur, Illinois.

Soon after, as Anastasio Bustamante’s presidency turned chaotic, supporters asked Santa Anna to take control of the provisional government. Santa Anna was made president for the fifth time, taking over a nation with an empty treasury. The war with France had weakened Mexico, and the people were discontented. Also, a rebel army led by Generals José Urrea and José Antonio Mexía was marching towards the capital in opposition to Santa Anna. Commanding the army, Santa Anna crushed the rebellion in Puebla. Santa Anna ruled in a more dictatorial way than during his first administration. His government banned anti-Santanista newspapers and jailed dissidents to suppress opposition. In 1842, he directed a military expedition into Texas. It committed numerous casualties with no political gain; but Texans began to be persuaded of the potential benefits of annexation by the more powerful U.S. Santa Anna was unable to control the Mexican congressional elections of 1842. The new congress was composed of men of principles who vigorously opposed the autocratic leader.

Trying to restore the treasury, Santa Anna raised taxes, but this aroused resistance. Several Mexican states stopped dealing with the central government, and Yucatán and Laredo declared themselves independent republics. With resentment growing, Santa Anna stepped down from power. Fearing for his life, he tried to elude capture, but in January 1845 he was apprehended by a group of Indians near Xico, Veracruz. They turned him over to authorities, and Santa Anna was imprisoned. His life was spared, but the dictator was exiled to Cuba.

Mexican–American War

In 1846, Mexico again invaded Texas, hoping to regain Texas; the United States then declared war on Mexico, hoping to extinguish the weak Mexican land claims to western Indian lands that Mexico had inherited from the Spanish. The Indians never recognized Spanish land claims, and had driven the Spanish and Mexicans from Texas, Arizona, and most of New Mexico. While the Spanish had taken possession of some Indian land in California, California was not bound to Mexico by economic ties. It was closer bound to the USA. Santa Anna wrote to Mexico City saying he had no aspirations to the presidency, but would eagerly use his military experience to fight off the foreign invasion of Mexico as he had in the past. President Valentín Gómez Farías was desperate enough to accept the offer and allowed Santa Anna to return. Meanwhile, Santa Anna had secretly been dealing with representatives of the U.S., pledging that if he were allowed back in Mexico through the U.S. naval blockades, he would work to sell all contested territory to the U.S. at a reasonable price. Once back in Mexico at the head of an army, Santa Anna reneged on both of these agreements. Santa Anna declared himself president again and unsuccessfully tried to fight off the U.S. invasion. (His leadership was said to inspire the sea shanty “Santianna”.)

President for the last time

Following defeat in the Mexican-American War in 1848, Santa Anna went into exile in Kingston, Jamaica. Two years later, he moved to Turbaco,Colombia. In April 1853, he was invited back by rebellious conservatives with whom he succeeded in re-taking the government. This administration was no more successful than his earlier ones. He funneled government funds to his own pockets, sold more territory to the U.S. with the Gadsden Purchase, and declared himself dictator-for-life with the title “Most Serene Highness.” The Plan of Ayutla of 1854 removed Santa Anna from power. Despite his generous payoffs to the military for loyalty, by 1855 even conservative allies had seen enough of Santa Anna. That year a group of liberals led by Benito Juárez andIgnacio Comonfort overthrew Santa Anna, and he fled back to Cuba. As the extent of his corruption became known, he was tried in absentia for treason; all his estates were confiscated by the government.

Post Presidency

From 1848 to 1874, Santa Anna lived in exile in Cuba, the United States, Colombia, and the then Danish island of Saint Thomas. In 1865 he attempted to return and offer his services during the French Invasion posing once again as the country’s defender and savior, only to be refused by Juarez who was well aware of Santa Anna’s character. In 1869, the 74-year-old Santa Anna was living in exile in Staten Island, New York and was trying to raise money for an army to return and take over Mexico City. During his time living in New York City, he is credited with bringing in the first shipments of chicle, the base of chewing gum. He failed to profit from this, since his plan was to use the chicle to replace rubber in carriage tires, which was tried without success. Thomas Adams, the American assigned to aid Santa Anna while he was in the U.S., experimented with chicle in an attempt to use it as a substitute for rubber. He bought one ton of the substance from Santa Anna, but his experiments proved unsuccessful. Instead, Adams helped to found the chewing gum industry with a product that he called “chiclets“. During his many years in exile, Santa Anna was a passionate fan of the sport of cockfighting. He would invite breeders from all over the world for matches and is known to have spent tens of thousands of dollars on prize roosters.

Personal life

Santa Anna was a devoted collector of Napoleonic artifacts, and adopted the nickname the “Napoleon of the West” after the Telegraph and Texas Register referred to him as such. His other nickname was “The Eagle.” Santa Anna married Inés García in 1825 and fathered four children: María de Guadalupe, María del Carmen, Manuel, and Antonio López de Santa Anna y García. Two months after García’s death in 1844, the 50-year-old Santa Anna married 16-year-old María de los Dolores de Tosta. The couple rarely lived together; de Tosta resided primarily in Mexico City and Santa Anna’s political and military activities took him around the country. They had no children, leading biographer Will Fowler to speculate that the marriage was either primarily platonic or that de Tosta was infertile. Several women claimed to have borne Santa Anna illegitimate children. In his will, Santa Anna acknowledged and made provisions for four: Paula, María de la Merced, Petra, and José López de Santa Anna. Biographers have identified three more: Pedro López de Santa Anna, and Ángel and Augustina Rosa López de Santa Anna.

In 1874, he took advantage of a general amnesty and returned to Mexico. Crippled and almost blind from cataracts, he was ignored by the Mexican government that same year at the anniversary of the Battle of Churubusco. Two years later, Santa Anna died at his home in Mexico City on 21 June 1876 at age 82. He was buried in Panteón del Tepeyac Cemetery.