September 13, 2012 –Although many in Canada and most in the United States recall the battle between Texian Militia, lead by co-commanders James Bowie and William B. Travis and the Mexican Army under under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna, (Remember the Alamo) not many know about the equally pivotal Battle of Chapultepec Castle 165 years ago and the bravery of six Mexican teenage military cadets on September 13, 1847 during the Mexican-American War.

The Mexican-American War was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas and the continued interest of the American government to expand westward. The conflict included the American President ordering the army under General Winfield Scott, which was transported to the port of Veracruz by sea, to begin an invasion of the Mexican heartland with 8500 troops. Scott led the first major amphibious landing in the history of the U.S. in preparation for the Siege of Veracruz. Many future American Civil War notables participated in this invading force including Robert E. Lee, George Meade, Ulysses S. Grant and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. After landing the American force in Veracruz Scott advanced on Mexico City.

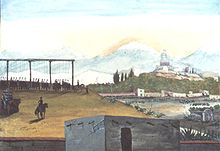

General Antonio López de Santa Anna was in command of the army at Mexico City and understood that Chapultepec Castle was an important position for the defense of the city. The castle sat atop a 200-foot (60 m) tall hill which in recent years was being used as the Mexican Military Academy. General Nicolás Bravo, however, had fewer than 1,000 men, including about 200 cadets from the military academy, some as young as 13 years old with which to defend the castle. On September 8, 1847, in the costly Battle of Molino del Rey, U.S. forces had managed to drive other Mexicans troops from their positions near the base of Chapultepec Castle guarding Mexico City from the west.

The Americans began an artillery barrage against Chapultepec Castle at dawn on September 12, 1847 was halted at sunset and resumed at first light the next day, September 13. At 08:00, the bombardment was halted and Winfield Scott ordered the charge. The greatly outnumbered defenders battled General Scott’s troops for about two hours before General Bravo ordered retreat, however the six Niños Héroes refused to fall back and fought to the death. Legend has it that the last of the six, Juan Escutia, leapt from Chapultepec Castle wrapped in the Mexican flag to prevent the flag from being taken by the enemy. According to the later account of an unidentified US officer, “about a hundred” cadets between the ages of 10 and 16 were among the “crowds” of prisoners taken after the Castle’s capture. In the course of the fighting at the Battle of Chapultepec, Scott suffered around 860 casualties while Mexican losses are estimated at around 1,800 with an additional 823 captured.

A little known fact is 30 men from the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, a group of former United States Army soldiers who joined the Mexican side, were executed en masse during the battle. They had been previously captured at the Battle of Churubusco and were hanged with Chapultepec in view and that the precise moment of their death was to occur when the U.S. flag replaced the Mexican tricolor atop the citadel.

With the city’s defenses breached, Mexican commander General Antonio López de Santa Anna elected to abandon the capital that night. The following morning, Scott’s American forces entered the city shortly thereafter, large-scale fighting effectively ended with Mexico City’s fall and Scott later became military governor of the occupied Mexico City. Entering into negotiations, the conflict was ended by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in early 1848. The most important consequences of the war for the United States were the Mexican terms of surrender in which the Mexican territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México were ceded to the United States. In Mexico, the enormous loss of territory following the war encouraged its government to enact policies to colonize its remaining northern territories as a hedge against further losses.

Few know the efforts of the U.S. Marines in this battle and subsequent occupation of Mexico City are memorialized by the opening lines of the Marines’ Hymn, “From the Halls of Montezuma…” and tradition maintains that the red stripe worn on the trousers of the Blue Dress uniform, commonly known as the blood stripe, commemorates those Marine NCOs who died storming the castle of Chapultepec in 1847.

In 1947, the year of the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Chapultepec, U.S. President Harry S. Truman placed a wreath at the monument commemorating the Cadets and stood for a few moments of silent reverence. Asked by American reporters why he had gone to the monument, Truman said, “Brave men don’t belong to any one country. I respect bravery wherever I see it.”

The Niños Héroes aged 13-19 years old were:

- Juan de la Barrera

- Juan Escutia

- Francisco Márquez

- Agustín Melgar

- Fernando Montes de Oca

- Vicente Suárez