February 11, 2017 – Today is Day 1 on our February tour which Lisa and I are leading. Larry & Janet are four days ahead of us. Baja Amigos has 3 groups with over 20 RVs on Baja this month. February is very busy for Baja RV Caravans, 9 operating this month with a total 5 different companies.

We have a great group, all Canadians from BC and Alberta. This will be my only Blog on this tour as we have Rob Tellier on the tour who has agreed to be the featured guest Blogger. Rob operates GR8 Travel Tips, see: http://gr8traveltips.com/about/ his posts will be circulated to our contact list as the tour proceeds.

January on Baja was different for us as we did not lead our only January tour as we focused on managing the business. Our times included 7 days on Playa Santispac, 5 days at the Hotel Serenidad and 11 days at Rivera del Mar in Loreto. We were on the beach when the Baja Amigos Caravan arrived on Santispac. The beach was busy as there was 3 Caravans on the beach over a few days, over 75 RVs at one point for a first time in many years a 2nd row formed. Our beach experience included noisy and annoying generators. We are not talking about an hour here or there, but continuous use. We had a Class “A” Motorhome with the Baja Winters Caravan roll up beside us an immediately after parking turned on the generator. The water was calm, the sky was blue, the sun bright and no wind, just a serene beautiful Baja day except for the generator next door. Why you ask? The Motorhome was facing the bay, had the front blinds closed and was watching TV, over 3 days they hardly came out of the RV. Why the hell did you come to Baja?

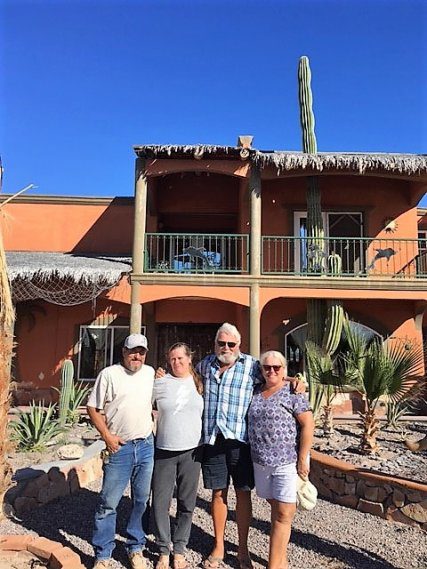

Good news I got lots of time in the Kayak, many sunrises on the water, you just cannot beat this experience. We were camped with our Kansas friends, Mike & Kelly and Roland & Janice. We were also able to spend time with Bruce & Marian (Vancouver Island), Steve & Dale and Gary & Linda (Placerville, CA). Bruce & Marian took us out to see the Whale Sharks, we found them not far off the beach at Playa Coyote, this was a fantastic experience. After the beach we headed south to Loreto, as it turned out for most of our time in January. We had planned to return to Playa Santispac but the wind came up and we decided to stay put. The first few days we camped with our Kansas friends before they headed further south. During our time we connected with Luis & Cindy at their house on the beach north of Loreto. We joined Luis & Cindy and their neighbours at a “Happy Hour” at the Mision Hotel (5 Star Hotel in a 3 Star Town) on the Loreto Malecon. What a great deal; I had 2 Negro Modelo Draft, Lisa had 2 Pacifico Light, total was $75 Pesos ($3.75 USD). We then joined the group for dinner at “Super Burro”, a bit windy and cold, but great food at a very reasonable price ($235 Pesos-$11.75 USD), reminded us of “La Pasadita” in Pescadero, just a larger scale. We also joined Roland & Janice at the Oasis Hotel Restaurant on the beach at the south end of town, very nice. Of course a stop in Loreto means lunch at “Del Boracho”, staff is still great and food good, lots of opinions about the new owners.

We then made the decision it was time to head north to prepare for our February tour. We were not sure what would happen with another increase in the gas price, possibly on February 1st. We made Mario’s in Guerrero Negro after leaving Loreto, arrived before 3PM. Headed off early and arrived before 3PM at the Baja Fiesta Restaurant in Vicente Guerrero. On the last 30 km or so before arrival, we noticed some jerking and banging, we thought from the Trailer. After getting set at Baja Fiesta we asked Cecilla to call a Mechanic, our Spring Link Brackets were worn out and needed replacing, fortunately we had some spares. We also found out all the wheel bearings, replaced in September by an RV Shop in Surrey, were loose, clearly a sloppy installation. Back on the road the next morning continuing our journey north and the jerking and banging continued.

Within an hour we thought it may be the transmission, we were stunned as it had been replaced less than 50,000 km earlier in October of 2015. We made the decision to head directly to the border and see if we could make it, fortunately we did. During this time an wrench light appeared on the dash that indicated a different issue. We dropped the Trailer at Oak Creek, the Van at El Cajon Ford. At first it was uncertain if the warranty applied and how quickly it could be repaired. Good news, we still had 300 km left on the Warranty, the repair should be finished on Tuesday, February 7. Just in time for us to meet our group for the February 10th tour in Potrero.

The repaired Transmission comes with a 1 year, 12,000 mile warranty, we just hope we can finish our Baja season.

Did you know?

Mezcal (or mescal) (i/mɛsˈkæl/) is a distilled alcoholic beverage made from any type of agave plant native to Mexico. The word mezcal comes from Nahuatl mexcalli [meʃˈkalːi] metl [met͡ɬ] and ixcalli [iʃˈkalːi] which means “oven-cooked agave”. The agave grows in many parts of Mexico, though most mezcal is made in Oaxaca. It can also be made in Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Zacatecas, Michoacan and the recently approved Puebla. A saying attributed to Oaxaca regarding the drink is: “Para todo mal, mezcal, y para todo bien, también.” (“For every ill, Mezcal, and for every good as well.”).

The agave was one of the most sacred plants in pre-Spanish Mexico, and had a privileged position in religious rituals, mythology and the economy. Cooking of the “piña” or heart of the agave and fermenting its juice was practiced. The origin of this drink has a myth. It is said that a lightning bolt struck an agave plant, cooking and opening it, releasing its juice. For this reason, the liquid is called the “elixir of the gods”. However, it is not certain whether the native peoples of Mexico had any distilled liquors prior to the Spanish Conquest.

The Spanish had known distillation processes since the eighth century and had been used to drinking hard liquor. They brought a supply with them from Europe, but when this ran out, they began to look for a substitute. They had been introduced to pulque and other drinks based on the agave or agave plant, so they began experimenting to find a way to make a product with a higher alcohol content. Soon, the conquistadors began to make a distillable fermented mash. The result was mezcal. Today, mezcal is still made from the heart of the agave plant, called the piña, much the same way it was 200 years ago, in most places. The drinking of alcoholic beverages such as pulque was strongly restricted in the pre-Hispanic period. Taboos against drinking to excess fell away after the conquest, resulting in problems with public drunkenness and disorder. This conflicted with the government’s need for the tax revenue generated by sales, leading to long intervals promoting manufacturing and consumption, punctuated by brief periods of severe restrictions and outright prohibition.

Travelers during the colonial period of Mexico frequently mention mezcal, usually with an admonition as to its potency. Alexander von Humboldt mentions it in his Political Treatise on the Kingdom of New Spain (1803), noting that a very strong version of mezcal was being manufactured clandestinely in the districts of Valladolid (Morelia), Mexico State, Durango and Nuevo León. He mistakenly observed that mezcal was obtained by distilling pulque, contributing to its myth and mystique. Spanish authorities, though, treated pulque and mezcal as separate products for regulatory purposes.

Edward S. Curtis described in his seminal work The North American Indian the preparation and consumption of mezcal by the Mescalero Apache Indians: “Another intoxicant, more effective than túlapai, is made from the mescal–not from the sap, according to the Mexican method, but from the cooked plant, which is placed in a heated pit and left until fermentation begins. It is then ground, mixed with water, roots added, and the whole boiled and set aside to complete fermentation. The Indians say its taste is sharp, like whiskey. A small quantity readily produces intoxication.”. This tradition has recently been revived in the Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

The agave plant is part of the Agavaceae family, which has almost 200 subspecies. The mezcal agave has very large, thick leaves with points at the ends. When it is mature, it forms a “piña” or heart in the center from which juice is extracted to convert into mescal . It takes between seven and fifteen years for the plant to mature, depending on the species and whether it is cultivated or wild. Agave fields are a common sight in the semi-desert areas of Oaxaca state and other parts of Mexico.

Mezcal is made from over 30 agave species, varietals, and subvarietals, by contrast with tequila, which is made only with blue agave; of these, seven are particularly notable. There is no exhaustive list, as the regulations allow any agaves, provided that they are not used as the primary material in other governmental Denominations of Origin. Notably, this regulation means that mezcal cannot be made from blue agave. The term silvestre “wild” is sometimes found, but simply means that the agaves are wild (foraged, not cultivated); it is not a separate varietal. Most commonly used is espadín “smallsword” (Agave angustifolia (Haw.), var. espadín), the predominant agave in Oaxaca. The next most important are arroqueño (Agave americana (L.) var. oaxacensis, sub-varietal arroqueño), cirial (Agave Karwinskii (Zucc.)), barril (Agave rodacantha (Zucc.) var. barril), mexicano (Agave macroacantha or Agave rhodacantha var. mexicano, also called dobadaan)[a] and cincoañero (Agave canatala roxb). The most famous wild agave is tobalá (Agave potatorum (Zucc.)). Others include madrecuixe, and tepeztate. Various other varietals of Agave karwinskii are also used, such as bicuixe and madrecuixe.

Traditionally, mezcal is handcrafted by small-scale producers. A village can contain dozens of production houses, called fábricas or palenques, each using methods that have been passed down from generation to generation, some using the same techniques practiced 200 years ago. The process begins by harvesting the plants, which can weigh 40 kg each, extracting the piña, or heart, by cutting off the plant’s leaves and roots. The piñas are then cooked for about three days, often in pit ovens, which are earthen mounds over pits of hot rocks. This underground roasting gives mezcal its intense and distinctive smoky flavor. They are then crushed and mashed (traditionally by a stone wheel turned by a horse) and then left to ferment in large vats or barrels with water added.

The mash is allowed to ferment, the resulting liquid collected and distilled in either clay or copper pots which will further modify the flavor of the final product. The distilled product is then bottled and sold. Unaged mezcal is referred to as joven, or young. Some of the distilled product is left to age in barrels between one month and four years, but some can be aged for as long as 12 years. Mezcal can reach an alcohol content of 55%. Like tequila, mezcal is distilled twice. The first distillation is known as punta, and comes out at around 75 proof (37.5% alcohol by volume). The liquid must then be distilled a second time to raise the alcohol percentage.

Mezcal is highly varied, depending on the species of agave used, the fruits and herbs added during fermentation and the distillation process employed, creating subtypes with names such as de gusano, tobalá, pechuga, blanco, minero, cedrón, de alacran, creme de café and more. A special recipe for a specific mezcal type known as pechuga uses cinnamon, apple, plums, cloves, and other spices that is then distilled through chicken, duck, or turkey breast. It is made when the specific fruits used in the recipe are available, usually during November or December. Other variations flavor the mash with cinnamon, pineapple slices, red bananas, and sugar, each imparting a particular character to the mezcal. Most mezcal, however, is left untouched, allowing the flavors of the agave used to come forward.

Not all bottles of mezcal contain a “worm” (actually the larva of a moth, Hypopta agavis that can infest agave plants), but if added, it is added during the bottling process. There are conflicting stories as to why such would be added. Some state that it is a marketing ploy. Others state that it is there to prove that the mezcal is fit to drink, and still others state that the larva is there to impart flavor. The two types of mezcal are those made of 100% agave and those mixed with other ingredients, with at least 80% agave. Both types have four categories. White mezcal is clear and hardly aged. Dorado (golden) is not aged but a coloring agent is added. This is more often done with a mixed mezcal. Reposado or añejado (aged) is placed in wood barrels from two to nine months. This can be done with 100% agave or mixed mezcals. Añejo is aged in barrels for a minimum of 12 months. The best of this type are generally aged from 18 months to three years. If the añejo is of 100% agave, it is usually aged for about four years.

Mexico has about 330,000 hectares cultivating agave for mezcal, owned by 9,000 producers. Over 6 million liters are produced in Mexico annually, with more than 150 brand names. The industry generates about 29,000 jobs directly and indirectly. Certified production amounts to more than 2 million liters; 434,000 liters are exported, generating 21 million dollars in income. To truly be called mezcal, the liquor must come from certain areas. States that have certified mezcal agave growing areas with production facilities are Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas. About 30 species of agave are certified for use in the production of mezcal. Oaxaca has 570 of the 625 mezcal production facilities in Mexico, but some in-demand mezcals come from Guerrero, as well. In Tamaulipas, 11 municipalities have received authorization to produce authentic mezcal with the hopes of competing for a piece of both the Mexican national and international markets. The agave used here is agave Americano, agave verde or maguey de la Sierra, which are native to the state.

In Mexico, mezcal is generally drunk straight, not mixed in a cocktail. Mezcal is generally not mixed with any other liquids, but is often accompanied with sliced oranges sprinkled with a mixture of ground fried larvae, ground chili peppers, and salt called sal de gusano, which literally translates as “worm salt”. In the last decade or so, mezcal, especially from Oaxaca, has been exported. Exportation has been on the increase and government agencies have been helping smaller-scale producers obtain the equipment and techniques needed to produce higher quantities and qualities for export. The National Program of Certification of the Quality of Mezcal certifies places of origin for export products. Mezcal is sold in 27 countries on three continents. The two countries that import the most are the United States and Japan. In the United States, a number of entrepreneurs have teamed up with Mexican producers to sell their products in the country, by promoting its handcrafted quality, as well as the Oaxacan culture strongly associated with it.

The state of Oaxaca sponsors the International Mezcal Festival every year in the capital city, Oaxaca de Juárez. There, locals and tourists can sample and buy a large variety of mezcals made in the state. Mezcals from other states, such as Guerrero, Guanajuato, and Zacatecas also participate. This festival was started in 1997 to accompany the yearly Guelaguetza festival. In 2009, the festival had over 50,000 visitors, and brought in 4 million pesos to the economy.