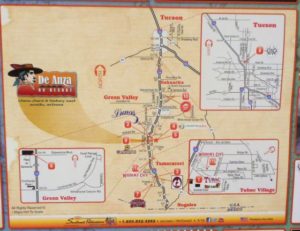

October 25, 2018 – We have finally arrived at the De Anza RV Resort in Amado, AZ. This is where we will meet our 45 Day Mexico Mainland group heading to Mexico City and back with many memorable stops in between. We actually leave this RV Park on October 31 as a group and meet up with Paul Beddows in Nogales, AZ. We will cross with Paul and a couple of others early on November 1st and make our way to KM 21 to process all the paperwork required for this next Mexican Adventure.

October 25, 2018 – We have finally arrived at the De Anza RV Resort in Amado, AZ. This is where we will meet our 45 Day Mexico Mainland group heading to Mexico City and back with many memorable stops in between. We actually leave this RV Park on October 31 as a group and meet up with Paul Beddows in Nogales, AZ. We will cross with Paul and a couple of others early on November 1st and make our way to KM 21 to process all the paperwork required for this next Mexican Adventure.

I must say our southbound journey starting on Sunday, October 14 has been memorable and includes “the Good, the Bad and the Ugly”. Definitely the “Good” has been the sunny skies with little wind. Departure day saw 6C for a low and 17C for a high on our arrival in Yakima. Taking Hwy 2 east at Everett, WA, thru Stevens Pass, Leavenworth into the US Okanagan was wonderful with stunning fall colours everywhere. We arrived in Yakima at about 3pm and parked at the Walmart for our usual shop on arrival to the US. This Walmart has permitted overnight RV parking since it was built, but no longer. Before you say “VISA or Master Card” we were told to leave, thankfully the Security Guard sent us to the nearby “Legends” Yakama Indian Casino (488 km day). We signed up for a Players Card and won a “Free Buffet” each! Free dinner, free stay and we did not gamble (to tired). Overnight we went down to 1C, it and it kept getting colder the further south we went.

I must say our southbound journey starting on Sunday, October 14 has been memorable and includes “the Good, the Bad and the Ugly”. Definitely the “Good” has been the sunny skies with little wind. Departure day saw 6C for a low and 17C for a high on our arrival in Yakima. Taking Hwy 2 east at Everett, WA, thru Stevens Pass, Leavenworth into the US Okanagan was wonderful with stunning fall colours everywhere. We arrived in Yakima at about 3pm and parked at the Walmart for our usual shop on arrival to the US. This Walmart has permitted overnight RV parking since it was built, but no longer. Before you say “VISA or Master Card” we were told to leave, thankfully the Security Guard sent us to the nearby “Legends” Yakama Indian Casino (488 km day). We signed up for a Players Card and won a “Free Buffet” each! Free dinner, free stay and we did not gamble (to tired). Overnight we went down to 1C, it and it kept getting colder the further south we went.

Monday we were off to Idaho and landed in Boise at the Hi Valley RV Park on the southeast side of town, this was a long day (566 km day). Easy in, easy out, $32 for the night however the Wi-Fi did not work in the Trailer. We used Lisa’s Hot Spot on her smart phone to check messages. 15C was our high, 0C was our low, more to come.

Tuesday we continued our journey south bound, our destination today was Wells, Nevada and landed at the Angel Lake RV Park. However this would be a shorter day (406 km day). No lake to be seen at Angel Lake, but easy to find, pull thru sights, clean washrooms and plenty of hot water in the showers, Wi-fi worked well too. What is the aversion to making level sites in a gravel parking lot? How hard can it be? We had to put the trailer on blocks and disconnect the trailer to level it. We actually had considered staying longer in the north as we had the time, but it was to darn cold. We struggled to 13C for a high and overnight it dropped to -2C, brrrr (we were at 5600′). Sometime over night the furnace shut off, looks like the gas ran out, this was “Bad”. I switched tanks but to no avail. We sorted the gas was to cold, near liquid and we could not get the furnace started. We plugged in the electric heater to take the frost off then headed south again. This time to Las Vegas where it was warmer for sure.

It was a very long day but we made Las Vegas and booked into the Road Runner RV Park, thank goodness (675 km day). We had noticed for a while that Lulu was drinking a lot and peeing a lot, off to the Vet it was. Then it got “Ugly” turns out Lulu has diabetes, very treatable but expensive, with tests, vet visits, meds, needles and special food we are almost at $1000 USD and much more to come, ouch! But we love our Lulu, however the 5K USD for potential cataracts are a none starter, we will get her sunglasses. When we left Las Vegas after 3 days the low was 17C and the high 31C, much better.

Next we were off to Buckeye, AZ and the Leaf Verde RV resort for some much needed pool time and perhaps some pickle ball (448 km day). Not so fast! Less an hour out from our destination we picked up a rock in the windshield, bang, just as the truck hit 10,000 km. First of order on arrival was to find someone to make the windshield repair. Did that, got set up, had a beer (not many these days) and enjoyed the breeze outside at 34C (84F). Election night back home (Saturday, October 20) and am still interested in outcomes and local races. No Wi-Fi across the RV Park, only the Office building. No problem, the RV Park offered AireBeam Broadband Wi-Fi at $8.95 USD for 3 days, that should be easy? Not so fast; signed up, paid, created a Username and Password and good to go? Nope! 12 hours later, 8 contacts to the support line by email and phone and still no help or Wi-Fi. I was calmer the next day but still am very frustrated. I stopped into the Office when it opened the next morning and Connie was very helpful including calling the Owner. Within 20 minutes everything was resolved, easy fix, I had written down the Username wrong. I am sure the owner will ask his support staff what they have been doing for 18 hours. Good thing we went to the top, the rep we phoned phone us near 5pm, the support center almost 24 hours after our first call for help. Our stay at Leaf Verde included some good pool time and local shopping. Jason from USA Replacement Auto Glass arrived on schedule and replaced the windshield for $200 cash, very happy!

Wednesday we continued our southern direction heading to the Desert Diamond Casino (281 km) for the complimentary buffet free RV parking. We arrived after lunch (and a visit to Camping World) and set up with many other RVs. After an all important “Siesta” we headed for the Buffet, after the $10 discount coupon and 2 for 1 option, dinner was free, no complaints for sure. We lost a few dollars then headed to the Arctic Fox to retire for the evening. 13C for an overnight low, the high was 30C.

Today we left early and continued south, stopping at the big Ms and the Bank of America to order some pesos for the tour. We arrived at the De Anza RV Resort (51 km) early and were welcomed by the owners, Amy & Bob. Looks like a wonderful facility with lots of amenities and we will try out the restaurant tonight (it was fabulous). Mike & Susan H. arrived yesterday and the rest will be here by Monday. Our adventure has almost began and we are very excited!

Did you know?

I have always wondered how many 1st Americans were present in North, Central and South America before the Europeans arrived. Not surprising the answer is not a simple one and the population figure indigenous peoples in the Americas before the 1492 voyage of Christopher Columbus have proven difficult to establish. Scholars rely on archaeological data and written records from settlers from Europe. Most scholars writing at the end of the 19th century estimated that the pre-Columbian population was as low as 10 million; by the end of the 20th century most scholars gravitated to a middle estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more. As we know contact with the Europeans led to the European colonization of the Americas, in which millions of immigrants from Europe eventually settled in the Americas.

The fact is as the population of African and Eurasian peoples in the Americas grew steadily, the indigenous population plummeted. Eurasian diseases such as influenza, bubonic plague and pneumonic plagues, yellow fever, smallpox, and malaria devastated the Native Americans, who did not have immunity to them. Conflict and outright warfare with Western European newcomers and other American tribes further reduced populations and disrupted traditional societies. The extent and causes of the decline have long been a subject of academic debate, along with its characterization as a genocide.

Population overview

Given the fragmentary nature of the evidence, even semi-accurate pre-Columbian population figures are impossible to obtain. Scholars have varied widely on the estimated size of the indigenous populations prior to colonization and on the effects of European contact. Estimates are made by extrapolations from small bits of data. In 1976, geographer William Denevan used the existing estimates to derive a “consensus count” of about 54 million people. Nonetheless, more recent estimates still range widely which means there is a lot of guessing going on.

Using an estimate of approximately 37 million people in Mexico, Central and South America in 1492 (including 6 million in the Aztec Empire, 5-10 million in the Mayan States, 11 million in what is now Brazil, and 12 million in the Inca Empire), the lowest estimates give a death toll due from disease of 90% by the end of the 17th century (nine million people in 1650). Latin America would match its 15th-century population early in the 19th century; it numbered 17 million in 1800, 30 million in 1850, 61 million in 1900, 105 million in 1930, 218 million in 1960, 361 million in 1980, and 563 million in 2005. In the last three decades of the 16th century, the population of present-day Mexico dropped to about one million people. The Maya population is today estimated at six (6) million, which is about the same as at the end of the 15th century, according to some estimates. In what is now Brazil, the indigenous population declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated four (4) million to some 300,000.

While it is difficult to determine exactly how many Natives lived in North America before Columbus, estimates range from a low of 2.1 million to 7 million people to a high of 18 million.

The aboriginal population of Canada during the late 15th century is estimated to have been between 200,000 and two (2) million, with a figure of 500,000 currently accepted by Canada’s Royal Commission on Aboriginal Health. Repeated outbreaks of Old-World infectious diseases such as influenza, measles and smallpox (to which they had no natural immunity), were the main cause of depopulation. This combined with other factors such as dispossession from European/Canadian settlements and numerous violent conflicts resulted in a forty- to eighty-percent aboriginal population decrease after contact. For example, during the late 1630s, smallpox killed over half of the Wyandot (Huron), who controlled most of the early North American fur trade in what became Canada. They were reduced to fewer than 10,000 people.

Historian David Henige has argued that many population figures are the result of arbitrary formulas selectively applied to numbers from unreliable historical sources. He believes this is a weakness unrecognized by several contributors to the field and insists there is not sufficient evidence to produce population numbers that have any real meaning. He characterizes the modern trend of high estimates as “pseudo-scientific number-crunching.” Henige does not advocate a low population estimate but argues that the scanty and unreliable nature of the evidence renders broad estimates inevitably suspect, saying “high counters” (as he calls them) have been particularly flagrant in their misuse of sources. Many population studies acknowledge the inherent difficulties in producing reliable statistics, given the scarcity of hard data. I would agree.

The population debate has often had ideological underpinnings. Low estimates were sometimes reflective of European notions of cultural and racial superiority (aka racism). Historian Francis Jennings argued, “Scholarly wisdom long held that Indians were so inferior in mind and works that they could not possibly have created or sustained large populations.” It is also important to remember that the indigenous population of the Americas in 1492 was not necessarily at a high point and may actually have been in decline in some areas. Indigenous populations in most areas of the Americas reached a low point by the early 20th century. In most cases, populations have since begun to climb.

According to Noble David Cook, a community of scholars have recently, albeit slowly, “been quietly accumulating piece by piece data on early epidemics in the Americas and their relation to subjugation of native peoples.” They now believe that widespread epidemic disease, to which the natives had no prior exposure or resistance, was the primary cause of the massive population decline of the Native Americans. Earlier explanations for the population decline of the American natives include the European immigrants’ accounts of the brutal practices of the Spanish conquistadores, as recorded by the Spaniards themselves. This was applied through the encomienda, which was a system ostensibly set up to protect people from warring tribes as well as to teach them the Spanish language and the Catholic religion, but in practice was tantamount to serfdom and slavery. The most notable account was that of the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, whose writings vividly depict Spanish atrocities committed in particular against the Taínos. It took five years for the Taíno rebellion to be quelled by both the Real Audiencia—through diplomatic sabotage, and through the Indian auxiliaries fighting with the Spanish. After Emperor Charles V personally eradicated the notion of the encomienda system as a use for slave labour, there were not enough Spanish to have caused such a large population decline. The second European explanation was a perceived divine approval, in which God removed the natives as part of His “divine plan” to make way for a new Christian civilization (convenient eh?). Many Native Americans also viewed their troubles in terms of religious or supernatural causes within their own belief systems.

Soon after Europeans and enslaved Africans arrived in the New World, bringing with them the infectious diseases of Europe and Africa, observers noted immense numbers of indigenous Americans began to die from these diseases. One reason this death toll was overlooked is that once introduced, the diseases raced ahead of European immigration in many areas. Disease killed a sizable portion of the populations before European written records were made. After the epidemics had already killed massive numbers of natives, many newer European immigrants assumed that there had always been relatively few indigenous peoples. The scope of the epidemics over the years was tremendous, killing millions of people—possibly in excess of 90% of the population in the hardest hit areas—and creating one of “the greatest human catastrophe in history, far exceeding even the disaster of the Black Death of medieval Europe”, which had killed up to one-third of the people in Europe and Asia between 1347 and 1351.

One of the most devastating diseases was smallpox, but other deadly diseases included typhus, measles, influenza, bubonic plague, cholera, malaria, tuberculosis, mumps, yellow fever and pertussis, which were chronic in Eurasia. This transfer of disease between the Old and New Worlds was later studied as part of what has been labeled the “Columbian Exchange”. The epidemics had very different effects in different regions of the Americas. The most vulnerable groups were those with a relatively small population and few built-up immunities. Many island-based groups were annihilated. The Caribs and Arawaks of the Caribbean nearly ceased to exist, as did the Beothuks of Newfoundland. While disease raged swiftly through the densely populated empires of Mesoamerica, the more scattered populations of North America saw a slower spread.

Virulence and mortality

Viral and bacterial diseases that kill victims before the illnesses spread to others tend to flare up and then die out. A more resilient disease would establish an equilibrium; if its victims lived beyond infection, the disease would spread further. The evolutionary process selects against quick lethality, with the most immediately fatal diseases being the most short-lived. A similar evolutionary pressure acts upon victim populations, as those lacking genetic resistance to common diseases die and do not leave descendants, whereas those who are resistant procreate and pass resistant genes to their offspring. For example, in the first fifty years of the sixteenth century, an unusually strong strain of syphilis killed a high proportion of infected Europeans within a few months; over time, however, the disease has become much less virulent.

Thus both infectious diseases and populations tend to evolve towards an equilibrium in which the common diseases are non-symptomatic, mild or manageably chronic. When a population that has been relatively isolated is exposed to new diseases, it has no resistance to the new diseases (the population is “biologically naive”). These people die at a much higher rate, resulting in what is known as a “virgin soil” epidemic. Before the European arrival, the Americas had been isolated from the Eurasian-African landmass. The peoples of the Old World had had thousands of years for their populations to accommodate to their common diseases.

The fact that all members of an immunologically naive population are exposed to a new disease simultaneously increases the fatalities. In populations where the disease is endemic, generations of individuals acquired immunity; most adults had exposure to the disease at a young age. Because they were resistant to reinfection, they are able to care for individuals who caught the disease for the first time, including the next generation of children. With proper care, many of these “childhood diseases” are often survivable. In a naive population, all age groups are affected at once, leaving few or no healthy caregivers to nurse the sick. With no resistant individuals healthy enough to tend to the ill, a disease may have higher fatalities.

The natives of the Americas were faced with several new diseases at once creating a situation where some who successfully resisted one disease might die from another. Multiple simultaneous infections (e.g., smallpox and typhus at the same time) or in close succession (e.g., smallpox in an individual who was still weak from a recent bout of typhus) are deadlier than just the sum of the individual diseases. In this scenario, death rates can also be elevated by combinations of new and familiar diseases: smallpox in combination with American strains of yaws, for example.

Other contributing factors:

Native American medical treatments such as sweat baths and cold water immersion (practiced in some areas) weakened some patients and probably increased mortality rates.

Europeans brought many diseases with them because they had many more domesticated animals than the Native Americans. Domestication usually means close and frequent contact between animals and people, which allows diseases of domestic animals to migrate into the human population when the necessary mutations occur.

The Eurasian landmass extends many thousands of miles along an east–west axis. Climate zones also extend for thousands of miles, which facilitated the spread of agriculture, domestication of animals, and the diseases associated with domestication. The Americas extend mainly north and south, which, according to the environmental determinist theory popularized by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, meant that it was much harder for cultivated plant species, domesticated animals, and diseases to migrate.

Biological warfare

Biological warfare

When Old World diseases were first carried to the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century, they spread throughout the southern and northern hemispheres, leaving the indigenous populations in near ruins. No evidence has been discovered that the earliest Spanish colonists and missionaries deliberately attempted to infect the American natives, and some effort was actually made to limit the devastating effects of disease before it killed off what remained of their forced slave labor under their encomienda system (which we plenty of on Baja). The cattle introduced by the Spanish contaminated various water reserves which Native Americans dug in the fields to accumulate rain water. In response, the Franciscans and Dominicans created public fountains and aqueducts to guarantee access to drinking water. But when the Franciscans lost their privileges in 1572, many of these fountains were not guarded any more and deliberate well poisoning may have happened. Although no proof of such poisoning has been found, some historians believe the decrease of the population correlates with the end of religious orders’ control of the water.

In the centuries that followed, accusations and discussions of biological warfare were common. Well-documented accounts of incidents involving both threats and acts of deliberate infection are very rare, but may have occurred more frequently than scholars have previously acknowledged. Many of the instances likely went unreported, and it is possible that documents relating to such acts were deliberately destroyed, or sanitized. By the middle of the 18th century, colonists had the knowledge and technology to attempt biological warfare with the smallpox virus. They well understood the concept of quarantine, and that contact with the sick could infect the healthy with smallpox, and those who survived the illness would not be infected again. Whether the threats were carried out, or how effective individual attempts were, is uncertain.

One such threat was delivered by fur trader James McDougall, who is quoted as saying to a gathering of local chiefs, “You know the smallpox. Listen: I am the smallpox chief. In this bottle I have it confined. All I have to do is to pull the cork, send it forth among you, and you are dead men. But this is for my enemies and not my friends.” Likewise, another fur trader threatened Pawnee Indians that if they didn’t agree to certain conditions, “he would let the smallpox out of a bottle and destroy them.” The Reverend Isaac McCoy was quoted in his History of Baptist Indian Missions as saying that the white men had deliberately spread smallpox among the Indians of the southwest, including the Pawnee tribe, and the havoc it made was reported to General Clark and the Secretary of War Artist and writer George Catlin observed that Native Americans were also suspicious of vaccination, “They see white men urging the operation so earnestly they decide that it must be some new mode or trick of the pale face by which they hope to gain some new advantage over them.” So great was the distrust of the settlers that the Mandan chief Four Bears denounced the white man, whom he had previously treated as brothers, for deliberately bringing the disease to his people.

During the Seven Years’ War, British militia took blankets from their smallpox hospital and gave them as gifts to two neutral Lenape Indian dignitaries during a peace settlement negotiation, according to the entry in the Captain’s ledger, “To convey the Smallpox to the Indians”. In the following weeks, the high commander of the British forces in North America conspired with his Colonel to “Extirpate this Execreble Race” of Native Americans, writing, “Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them.” His Colonel agreed to try. Most scholars have asserted that the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic was “started among the tribes of the upper Missouri River by failure to quarantine steam boats on the river”, and Captain Pratt of the St. Peter “was guilty of contributing to the deaths of thousands of innocent people. The law calls his offense criminal negligence. Yet in light of all the deaths, the almost complete annihilation of the Mandans, and the terrible suffering the region endured, the label criminal negligence is benign, hardly befitting an action that had such horrendous consequences.” However, some sources attribute the 1836–40 epidemic to the deliberate communication of smallpox to Native Americans, with historian Ann F. Ramenofsky writing, “Variola Major can be transmitted through contaminated articles such as clothing or blankets. In the nineteenth century, the U. S. Army sent contaminated blankets to Native Americans, especially Plains groups, to control the Indian problem.” Well into the 20th century, deliberate infection attacks continued as Brazilian settlers and miners transported infections intentionally to the native groups whose lands they coveted.”

Vaccination

After Edward Jenner’s 1796 demonstration that the smallpox vaccination worked, the technique became better known and smallpox became less deadly in the United States and elsewhere. Many colonists and natives were vaccinated, although, in some cases, officials tried to vaccinate natives only to discover that the disease was too widespread to stop. At other times, trade demands led to broken quarantines. In other cases, natives refused vaccination because of suspicion of whites. The first international healthcare expedition in history was the Balmis expedition which had the aim of vaccinating indigenous peoples against smallpox all along the Spanish Empire in 1803. In 1831, government officials vaccinated the Yankton Sioux at Sioux Agency. The Santee Sioux refused vaccination, and many died.

While epidemic disease was a leading factor of the population decline of the American indigenous peoples after 1492, there were other contributing factors, all of them related to European contact and colonization. One of these factors was warfare. According to demographer Russell Thornton, although many lives were lost in wars over the centuries, and war sometimes contributed to the near extinction of certain tribes, warfare and death by other violent means was a comparatively minor cause of overall native population decline. From the U.S. Bureau of the Census in 1894: “The Indian wars under the government of the United States have been more than 40 in number. They have cost the lives of about 19,000 white men, women and children, including those killed in individual combats, and the lives of about 30,000 Indians. The actual number of killed and wounded Indians must be very much higher than the given… Fifty percent additional would be a safe estimate…”

There is some disagreement among scholars about how widespread warfare was in pre-Columbian America, but there is general agreement that war became deadlier after the arrival of the Europeans and their firearms. The South or Central American infrastructure allowed for thousands of European conquistadors and tens of thousands of their Indian auxiliaries to attack the dominant indigenous civilization. Empires such as the Incas depended on a highly centralized administration for the distribution of resources. Disruption caused by the war and the colonization hampered the traditional economy, and possibly led to shortages of food and materials. The Arauco War, Chichimeca War, Red Cloud’s War, Seminole Wars, War of 1812, Pontiac’s Rebellion, Beaver Wars, French-Indian War, American Civil War, American Revolution, Modoc War, Oka Crisis, Battle of Cut Knife, all represented either pyrrhic victories by colonial forces, outright defeat, military stalemates, or further alliance-politics. Across the western hemisphere, war with various Native American civilizations constituted alliances based out of both necessity or economic prosperity and, resulted in mass-scale intertribal warfare. European colonization in the North American continent also contributed to a number of wars between Native Americans, who fought over which of them should have first access to new technology and weaponry—like in the Beaver Wars.

Exploitation

Some Spaniards objected to the encomienda system, notably Bartolomé de las Casas, who insisted that the Indians were humans with souls and rights. Due to many revolts and military encounters, Emperor Charles V helped relieve the strain on both the Indian laborers and the Spanish vanguards probing the Caribana for military and diplomatic purposes. Later on, New Laws were promulgated in Spain in 1542 to protect isolated natives, but the abuses in the Americas were never entirely or permanently abolished. The Spanish also employed the pre-Columbian draft system called the mita and treated their subjects as something between slaves and serfs. Serfs stayed to work the land; slaves were exported to the mines, where large numbers of them died. In other areas the Spaniards replaced the ruling Aztecs and Incas and divided the conquered lands among themselves ruling as the new feudal lords with often, but unsuccessful lobbying to the viceroys of the Spanish crown to pay Tlaxcalan war demnities. The infamous Bandeirantes from São Paulo, adventurers mostly of mixed Portuguese and native ancestry, penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves. Serfdom existed as such in parts of Latin America well into the 19th century, past independence.

Pre-Columbian Americas – Now this is really interesting!

Pre-Columbian Americas – Now this is really interesting!

Genetic diversity and population structure in the American land mass using DNA micro-satellite markers (genotype) sampled from North, Central, and South America have been analyzed against similar data available from other indigenous populations worldwide. The Amerindian populations show a lower genetic diversity than populations from other continental regions. Observed is both a decreasing genetic diversity as geographic distance from the Bering Strait occurs and a decreasing genetic similarity to Siberian populations from Alaska (genetic entry point). Also observed is evidence of a higher level of diversity and lower level of population structure in western South America compared to eastern South America. A relative lack of differentiation between Mesoamerican and Andean populations is a scenario that implies coastal routes were easier than inland routes for migrating peoples (Paleo-Indians) to traverse. The overall pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were recently colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70-250), and then they grew by a factor of 10 over 800 – 1000 years. The data also show that there have been genetic exchanges between Asia, the Arctic and Greenland since the initial peopling of the Americas 15,000 to 30,000 years ago. What ever the number was a new study in early 2018 suggests that the effective population size of the original founding population of Native Americans was about 250 people. And what’s also very interesting is it took them only a thousand years to after crossing the Bering Strait to arrive at the southern tip of South America. Turns out after a couple of DNA tests (Heritage.com & Ancestary.ca) I myself am 3% to 8% Native American.