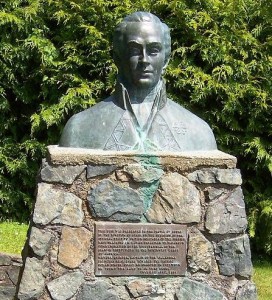

August 22, 2012 – Spanish claims to the west coast of North America date to the papal bull of 1493, and the Treaty of Tordesillas. In 1513, this claim was reinforced by Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the first European to sight the Pacific Ocean, when he claimed all lands adjoining this ocean for the Spanish Crown. Spain only started to colonize the claimed territory north of present day Mexico in the 18th century, after first settling Los Californias, first Baja then Alta California. The Spanish sent several explorers over the next 200 years that included Sub-Lt Don Manuel Quimper of the Spanish Navy.

Quimper and 6 other young naval lieutenants were transferred from Europe to bolster Spain’s Pacific strength. In 1790 Manuel Quimper, with officers López de Haro and Juan Carrasco, sailed the Princesa Real (a captured British vessel Princess Royal) into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, following up on voyage of Narváez the previous year. Quimper sailed to the eastern end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, discovering the San Juan Islands and many straits and inlets, he subsequently claimed the territory for Carlos IV. In June 1790 Manuel Quimper set sail from Nootka, then a temporary settlement on Vancouver Island, with orders to explore the newly discovered Strait of Juan de Fuca. Quimper was ordered to explore and trade in Juan de Fuca Strait. Quimper visited Chief WICKANANISHat Clayoquot Sound and then explored harbours and bays around present-day Victoria. Later he crossed the strait to explore Puerto Nunez Gaona (Neah Bay), which became the second Spanish post on the Northwest Coast. Having limited time he returned to Nootka without fully exploring the promising straits and inlets. Contrary winds made it impossible to sail the small vessel to Nootka, so Quimper went south to San Blas instead. In 1791 Quimper sailed the Princess Royal to Hawaii and the Philippines to return the vessel to its British owners.

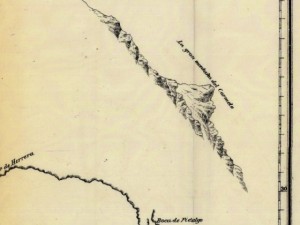

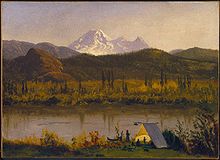

Accompanying Quimper was first-pilot Gonzalo Lopez de Haro, who drew detailed charts during the six-week expedition. Although Quimper’s journal of the voyage does not refer to the mountain, one of Haro’s manuscript charts includes a sketch of Mount Baker. The Spanish named the snowy volcano “La Gran Montana del Carmelo”, as it reminded them of the white-clad monks of the Carmelite Monastery. Indigenous people have known the mountain for thousands of years as Koma Kulshan or simply Kulshan. At 10,781 ft (3,286 m), it is the third-highest mountain in Washington State and the fifth-highest in the Cascade Range.

The British explorer George Vancouver left England a year later and his mission was to survey the northwest coast of America. Vancouver and his crew reached the Pacific Northwest coast in 1792. While anchored in Dungeness Bay on the south shore of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, third lieutenant Joseph Baker made an observation of what we now know as Mount Baker. The explorer George Vancouver renamed the mountain for 3rd Lieutenant Joseph Baker of HMS Discovery, who saw it on April 30, 1792.

This is an active glaciated andesitic stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc and the North Cascades of Washington State in the United States. Mount Baker has the second-most thermally active crater in the Cascade Range after Mount Saint Helens. About 31 miles (50 km) due east of the city of Bellingham, Whatcom County, Mount Baker is the youngest volcano in the Mount Baker volcanic field. While volcanism has persisted here for some 1.5 million years, the current glaciated cone is likely no more than 140,000 years old, and possibly no older than 80-90,000 years. Older volcanic edifices have mostly eroded away due to glaciation.

The present-day cone of Mount Baker is relatively young; it is perhaps less than 100,000 years old. The volcano sits atop a similar older volcanic cone called Black Buttes, which was active between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago. Much of Mount Baker’s earlier geological record eroded away during the last ice age (which culminated 15,000–20,000 years ago), by thick ice sheets that filled the valleys and surrounded the volcano. In the last 14,000 years, the area around the mountain has been largely ice-free, but the mountain itself remains heavily covered with snow and ice.

Baker has experienced several eruptions during the 19th century witnessed from the Bellingham area. A possible eruption was seen in June 1792 during the Spanish expedition of Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and Cayetano Valdés. In 1843, explorers reported a widespread layer of newly fallen rock fragments “like a snowfall” and that the forest was “on fire for miles around”. Geologists say it is highly unlikely that these fires were caused by ashfall, however, as charred material is not found with deposits of this fine-grained volcanic ash, which was almost certainly cooled in the atmosphere before falling. Rivers south of the volcano were reportedly clogged with ash, and Native Americans reported that many salmon perished. In early March 1975, a dramatic increase in fumarolic activity and snow melt in the Sherman Crater area of the mountain raised concern that an eruption might be imminent. Heat flow increased more than tenfold and additional monitoring equipment was installed and several geophysical surveys were conducted to try to detect the movement of magma. The increased thermal activity prompted public officials and Puget Power to temporarily close public access to the popular Baker Lake recreation area and to lower the reservoir’s water level by 10 meters. Activity gradually declined over the next two years but stabilized at a higher level than before 1975. The increased level of fumarolic activity has continued at Mount Baker since 1975, but no other changes suggest that magma movement is involved.

Glaciers and hydrology

There are ten main glaciers on the mountain. The Coleman Glacier is the largest; it has a surface area of 5.2 square kilometres (1,280 acres). The other large glaciers—which have areas greater than 2.5 square kilometres (620 acres)—are Roosevelt Glacier, Mazama Glacier, Park Glacier, Boulder Glacier, Easton Glacier and Deming Glacier. They all retreated during the first half of the century, advanced from 1950–1975 and have been retreating increasingly rapidly since 1980 (can you say climate change?). Mount Baker is drained on the north by streams that flow into the North Fork Nooksack River, on the west by the Middle Fork Nooksack River, and on the southeast and east by tributaries of the Baker River. Lake Shannon and Baker Lake are the largest nearby bodies of water, formed by two dams on the Baker River.