February 21, 2016 – It has been over a week since I blogged about our journey, unfortunately we have not had access to the internet at the campgrounds we have been staying at. Communication issues are remedied somewhat now that we have arrived in San Cristobal, also located in Chiapas, led again by Rafael & Eileen. We had been scheduled to stay at a Hotel parking lot which did not work out so good as it was really not big enough. Luckily the PEMEX Station 5661 was able to accommodate us at $40 pesos per day, no WiFi or showers though. It was the end to quite a drive from Agua Azul to San Cristobal, turns and topes, ups and downs, climbing to 7000 feet over 2000 meters and spectacular scenery all the way! Unfortunately I picked up a screw in a rear truck tire to boot. Fortunately Roland had air and a generator and I had the stuff from a can to seal the leak until a repair. After we got set up in the PEMEX we headed off to find a repair shop and mission accomplished.

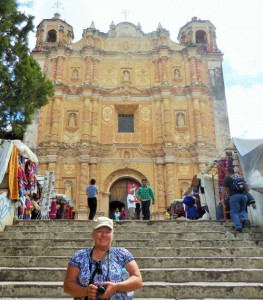

Today we headed into San Cristobal Centro and the city lived up to the hype, what a beautiful place. We were able to find parking near the Zocalo for our explorations and headed out to see what the town had to offer. We made our way up to a small church on a low rise for a better view of the city, very impressive church inside as well. Did lots of poking around in many shops and bought some more calcomanies (bumper stickers). Later we had lunch with many of the gang on a roof top restaurant on the main square, there was a celebration going on so lots of fireworks banging about. After lunch the group met at the van and we headed back to the RVs for a siesta and then at 5:30 pm out for some groceries, tomorrow another day in San Cristobal.

It seems ages ago (Feb. 11, 12,13,14) we were in in a campground just north of Chetumal, called Yax-Ha right on the water. Very quiet with well-kept grounds, many coconut palms and grass. The showers and washrooms were clean, the onsite restaurant inexpensive and the Wi-Fi excellent. During our stay we took the Kayak off the roof and put it in the ocean lagoon, it was a bit windy but myself and Rafael made the best of it as it was nice to get on the water. The first full day at the park we just kicked back and hung out, no excursions. Mike installed the new motor he received in Cancun for his slide and we did had our first Potluck Dinner which was fantastic. Saturday we headed into Chetumal in search of the local Mercado.

Our day trip to Chetumal was a real treat with a drive on an Oceanside road. I found the town very relaxed, with wide roads and few crazy drivers, I have to say this is a real departure from many of the larger cities. We found the local Mercado, next to a Museo about Mayans and nearby many small eateries. We enjoyed our tour of the market, purchased a few items, and Mike & Kelly joined us for lunch at a taco stop on the sidewalk. After we collected up the gang I decide to drive to the Belize border to see what that was all about. We discovered that Mexico and Belize had set up a Free Zone, where you could cross with valid passports and shop duty free. Most did not have their passports so we decided to visit the next day. Later that evening Rafael and I met with Jorge, Fina and Tio Ricardo Jimenez who had dropped by to meet me. Bety (Antonio & Bety from Bahia de Los Angeles) had contacted us and told us her Brother and Sister in Law lived in Chetumal, gave us his number and suggested we contact him. As it turns out her Uncle Ricardo was visiting from the US and came along as well. I really enjoyed meeting everyone particularly from Bety’s family, great folks for sure.

Valentine’s Day and we off to the Belize Free Zone with Passports in hand and then a scheduled swim at Bacalar Lagoon, Laguna de los Siete Colores (Lagoon of the seven Colours). The name comes from the fact that the shallow lake has a very light-coloured bottom and as the day moves along the colour of the water changes as with this reflecting sky. When we got to the border we parked and went directly to the Mexican Immigration Station at the entrance to the Belize free zone. Now we were asked for our Mexican Tourist Cards, not just our Passport as earlier informed. Some folks had them, others were not willing to give them up. Suddenly we had option B, as the Mexican immigration officer asked for $50 pesos each to venture across into Belize. The group quickly decided this was a way to sketchy a process and we had gone nowhere. What was it going to be like when we had to re-enter Mexico after visiting the free zone we asked ourselves? Us in Belize and our RVs in Mexico? I do not think so!

All righty then, we were off to our swimming appointment in Bacalar. When we arrived we found a nice spot, very inexpensive, $10 to park, $10 entry fee that included a swimming dock, restaurant, tables and chairs, change rooms, washrooms, even some shopping. Most had a good swim, very refreshing, had a bite to eat, and headed back to the RV Park in the early afternoon. Time to pack up the Kayak and other items then prepare for our group Valentine’s dinner organized by Marian and Anita down the street. Prior to our departure Roland had a Valentine for all the gals, definitely a nice touch. We sat on the patio outside on the water side and it was seafood all around. I had a shrimp dish that was very tasty and inexpensive, it was a memorable Valentine’s dinner.

Next day we all had to fill up with water and dump before departure, all organized by Rafael. It took a while but by 10: am we were off to Escarcega led by Mike & Kelly and eventually Palenque, Chiapas. The roads were good with only a couple of potholes to dodge, excellent payment and plenty wide. We stayed at Rancho Casado which was a large field set up for dry camping, with some water and electrical access, rudimentary showers and toilets. We were greeted by Howler monkeys on our arrival and after we set up Kelly brought out a game not dissimilar to Apples to Apples but for Adults. This was fun and we had lots of laughs, to add to the laughs Bruce demonstrated an acrobatic move rarely seen when his $5 special chair collapsed, fortunately he was uninjured.

8:30 am sharp we were off to Palenque. Drive was good, always slow when we encounter villages travelling from the state of Quintana Roo thru Tabasico into Chiapas. Quite the greeting when entering Chiapas, no “Welcome to Chiapas”, instead we drove into a massive security facility and submitted passports, Vehicle Registration, Import Permits and VIN Numbers checked. Interesting to say the least. We arrived in Palenque the town and decided to return for groceries. Got to the MayaBell Campground which has beautiful surroundings, right in the heart of the jungle, clean washrooms, showers, pool and nice restaurant. Set up and went for a swim, then into town for some supplies.

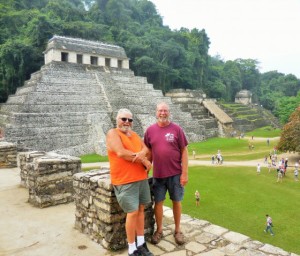

The next morning we were off to the Palenque Archeological site, led by the Steinfort’s, which is exceptional to see in this jungle setting. No big crowds and mostly European tourists, the site itself is massive. To date only 5% of the existing structures have been uncovered sitting on approximately 1 square mile. Over 1500 structures remain beneath the jungle on the mountain side into the valley. The weather was changing and the rain was upon us. Lisa and I went swimming in the pool back at MayaBell during one of these downpours, what a fabulous experience. It rained heavily off and on the rest of the afternoon and overnight however we were greeted with lots of blue sky in the morning. At 10:00 am the group headed out in the Baja Amigos Collectivo to Misal Ha, a very popular waterfall and possible swimming location not far away from Palenque. Some terrific scenery on our short drive as we climbed for 200’ (75m) to almost 1000’ (300m) into the jungle.

We arrived at the sign and were greeted by some folks collecting $10 pesos per person for entry, Ejido members. Travelling another 2 or 3 km we came across another collection, this time $20 pesos per person. Apparently the road to the falls crosses two (2) different Ejido lands, hence the two different collection points. $30 pesos is just more than $2 Canadian or $1.50 USD, certainly not much. The falls were worth every penny or in this case peso. Impressive as they thundered down, at least 100’, probably more than 30m. There was a walkway behind them that was deafening and you walk up the other side from below however with e the recent heavy rain these stairs were also a waterfall, it looked a bit sketchy. Swimming was possible but the walk to the pools was very slippery and the water very turbid, also likely from the heavy rains. Kelly found some great bumper stickers at a little shop on site. We returned back to Palenque as some folks needed an ATM and a couple of supplies. Later Mike offered to take his truck down the road for some agua purificado refills, I went along. The rest of the day was taken up mostly by a siesta until the Howler monkeys arrived poolside and circled up close and personal in the trees, very cool, lots of howling as well. Lulu was curious but also frightened.

The next morning, February 19, we headed off to Agua Azul, another must see location popular tourist stop, this time led by Rafael & Eileen. Although the drive was relatively short, less than 70 km or 45 miles, it took us almost 2 hours to reach our destination. It reminded me of the drive to Pender Harbour on the Sunshine Coast from Halfmoon Bay onwards, lots of winding road posted at 60 km (40 miles) and hour. Add some villages with topes and small children selling local produce then a road block, only a thin rope across the road, again with small children, very persistent in collecting 20 pesos for produce or just collecting. Aside from the delays the scenery was spectacular, mountainous and jungle all the way. The falls at Aguq Azul were equally spectacular as they made their way down the mountain slope 10 or 20 feet (3-6 m) at a time. Many shops selling locally produced goods and lots of choices to eat as well. After lunch the gals went shopping and most of the guys relaxed, soaking up the sun and enjoying a cold beverage. A local Victor stopped by and we had a good chat with him, I thought maybe he was 18 or 19, turns out he is 30 with 2 sons and has been married for 13 years. We met another couple from Canada, Fran & Doug who arrived later in the afternoon and are heading to Central America. They joined us for dinner at a local restaurant Victor recommended. Most had the fresh fish specialty, I had the breaded chicken, and dinner was delicious.

Did you know these basic facts?

The total population of Mexicans worldwide was 155 million, which includes 132 million Mexican citizens and 23 million of Mexican ancestry.

| Regions with significant populations in 2014 | |

| Mexico 119,530,753 | |

| United States | 35,320,579 |

| Canada | 97,055 |

| Spain | 21,107 |

| Guatemala | 14,481 |

| Germany | 14,156 |

| Colombia | 12,286 |

| Bolivia | 9,377 |

| Italy | 6,798 |

| Brazil | 6,625 |

| Argentina | 6,042 |

| United Kingdom | 5,297 |

| France | 4,601 |

| Paraguay | 4,187 |

| Costa Rica | 4,000 |

| Netherlands | 3,758 |

| Australia | 3,500 |

| Cuba | 2,757 |

| Belize | 2,351 |

Languages

Mexicans speak primarily Spanish although English is a common 2nd language. Mexicans also speak 62 indigenous linguistic languages.

Religion

Mexicans are primarily Roman Catholic, 82.7 %, 9.7 % are Protestants, 2.9 % follow Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and 4.7 % are non-religious.

Overview & Detail

Mexicans (Spanish: Mexicanos) are the people of the United Mexican States, a multiethnic country in North America, and those who identify with the Mexican cultural and/or national identity. The Mexica founded Mexico-Tenochtitlan in 1325 as an altepetl (city-state) located on an island in Lake Texcoco, in the Valley of Mexico. It became the capital of the expanding Mexica Empire in the 15th century, until captured by the Spanish in 1521. At its peak, it was the largest city in the Pre-Columbian Americas. It subsequently became a cabecera of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Today the ruins of Tenochtitlan are located in the central part of Mexico City.

The modern nation of Mexico achieved independence from the Spanish Empire; this began the process of forging a national identity that fused the cultural traits of indigenous pre-Columbian origin with those of European, particularly Iberian, ancestry. This led to what has been termed “a peculiar form of multi-ethnic nationalism.” The most spoken language by Mexicans is Mexican Spanish, but some may also speak languages from 62 different indigenous linguistic groups and other languages brought to Mexico by recent immigration or learned by Mexican immigrants residing in other nations. There are about 12 million Mexican nationals residing outside of Mexico, with about 11.7 million living in the United States. The larger Mexican diaspora can also include individuals that trace ancestry to Mexico and self-identify as Mexican.

History

The Mexican people have varied origins and an identity that has evolved with the succession of conquests among Amerindian groups and later by Europeans. The area that is now modern-day Mexico has cradled many predecessor civilizations, going back as far as the Olmec which influenced the latter civilizations of Teotihuacan (200 B.C. to 700 A.D.) and the much debated Toltec people who flourished around the 10th and 12th centuries A.D., and ending with the last great indigenous civilization before the Spanish Conquest, the Aztecs (March 13, 1325 to August 13, 1521). The Nahuatl language was a common tongue in the region of modern Central Mexico during the Aztec Empire, but after the arrival of Europeans the common language of the region became Spanish.

After the conquest of the Aztec empire, the Spanish re-administered the land and expanded their own empire beyond the former boundaries of the Aztec, adding more territory to the Mexican sphere of influence which remained under the Spanish Crown for 300 years. Cultural diffusion and intermixing among the Amerindian populations with the European created the modern Mexican identity which is a mixture of regional indigenous and European cultures that evolved into a national culture during the Spanish period. This new identity was defined as “Mexican“ shortly after the Mexican War of Independence and was more invigorated and developed after the Mexican Revolution when the Constitution of 1917 officially established Mexico as an indivisible pluri-cultural nation founded on its indigenous roots.

Definitions

Mexicano (Mexican) is derived from the word Mexico itself. In the principal model to create demonyms in Spanish, the suffix -ano is added to the name of the place of origin. It has been suggested that the name of the country is derived from Mextli or Mēxihtli, a secret name for the god of war and patron of the Mexicas, Huitzilopochtli, in which case Mēxihco means “Place where Huitzilopochtli lives”. Another hypothesis suggests that Mēxihco derives from a portmanteau of the Nahuatl words for “Moon” (Mētztli) and navel (xīctli). This meaning (“Place at the Center of the Moon”) might then refer to Tenochtitlan’s position in the middle of Lake Texcoco. The system of interconnected lakes, of which Texcoco formed the center, had the form of a rabbit, which the Mesoamericans pareidolically associated with the Moon. Still another hypothesis suggests that it is derived from Mēctli, the goddess of maguey.

The term Mexicano as a word to describe the different peoples of the region of Mexico as a single group emerged in the 16th century. In that time the term did not apply to a nationality nor to the geographical limits of the modern Mexican Republic. The term was used for the first time in the first document printed in Barcelona in 1566 which documented the expedition which launched from the port in Acapulco to find the best route which would favor a return journey from the Spanish East Indies to New Spain. The document stated: “el venturoso descubrimiento que los Mexicanos han hecho” (the venturous discovery that the Mexicans have made). That discovery led to the Manila galleon trade route and those “Mexicans” referred to Criollos, Mestizos and Amerindians alluding to a plurality of persons who participated for a common end: the conquest of the Philippines in 1565.

Ethnic groups

Mestizo Mexicans

President Porfirio Diaz was of Mestizo descent.

A large majority of Mexicans have been classified as “Mestizos”, meaning in modern Mexican usage that they identify fully neither with any indigenous culture nor with a particular European heritage, but rather identify as having cultural traits and heritage incorporating elements from indigenous and European traditions. By the deliberate efforts of post-revolutionary governments the “Mestizo identity” was constructed as the base of the modern Mexican national identity, through a process of cultural synthesis referred to as mestizaje [mestiˈsahe]. Mexican politicians and reformers such as José Vasconcelos and Manuel Gamio were instrumental in building a Mexican national identity on the concept of mestizaje.

Cultural policies in early post-revolutionary Mexico were paternalistic towards the indigenous people, with efforts designed to “help” indigenous peoples achieve the same level of progress as the rest of society, eventually assimilating indigenous peoples completely to Mestizo Mexican culture, working toward the goal of eventually solving the “Indian problem” by transforming indigenous communities into mestizo communities.

Since the mestizo identity promoted by the government is more of a cultural identity than a biological one it has achieved a strong influence in the country, with a good number of biologically white people identifying with it, leading to being considered mestizos in Mexico’s demographic investigations and censuses due the ethnic criteria having its base on cultural traits rather than biological ones. A similar situation occurs regarding the distinctions between indigenous peoples and mestizos: while the term mestizo is sometimes used in English with the meaning of a person with mixed indigenous and European blood, this usage does not conform to the Mexican social reality where a person of pure indigenous genetic heritage would be considered Mestizo either by rejecting his indigenous culture or by not speaking an indigenous language, and a person with a very low percentage of indigenous genetic heritage would be considered fully indigenous either by speaking an indigenous language or by identifying with a particular indigenous cultural heritage.

The term “Mestizo” is not in wide use in Mexican society today and has been dropped as a category in population censuses; it is, however, still used in social and cultural studies when referring to the non-indigenous part of the Mexican population. The word has somewhat pejorative connotations and most of the Mexican citizens who would be defined as mestizos in the sociological literature would probably self-identify primarily as Mexicans. In the Yucatán peninsula the word Mestizo is even used about Maya-speaking populations living in traditional communities, because during the caste war of the late 19th century those Maya who did not join the rebellion were classified as mestizos. In Chiapas the word “Ladino” is used instead of mestizo.

European Mexicans

White Mexicans are Mexican citizens of full European descent. Although Mexico does not have a racial census, some international organizations believe that Mexican people of Spanish or predominantly European descent make up approximately one-sixth (16.5%) of the country’s population. Another group in Mexico, the “mestizos”, also include people with varying amounts of European ancestry, with some having a European admixture superior to 90%. Because of this, the line between whites and mestizos has become rather blur, and the Mexican government decided to abandon racial classifications. Despite that extra-official sources estimate the modern white population of Mexico to be only 9-16%, in genetic studies Mexico consistently shows a European admixture comparable to countries that report white populations of 52% – 77% (in the case of Chile and Costa Rica, who average 51% & 60% European admixture respectively, while studies in the general Mexican population have found European ancestry ranging from 56% going to 60%, 64% and up to 78%). The differences between genetic ancestry and reported numbers could be attributed to the influence of the concept known as “mestizaje”, which was promoted by the post-revolutionary government in an effort to create a united Mexican cultural identity with no racial distinctions.

Europeans began arriving to Mexico with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, with the descendants of the conquistadors, along with new arrivals from Spain formed an elite but never a majority of the population. Intermixing would produce a mestizo group which would become the majority by the time of Independence, but power remained firmly in the hands of the elite, called “criollo.” While most of European or Caucasian migration into Mexico was Spanish during the Spanish period, in the 19th and 20th centuries European and European derived populations from North and South America did immigrate to the country. However, at its height, the total immigrant population in Mexico never exceeded twenty percent of the total. Many of these immigrants came with money to invest and/or ties to allow them to become prominent in business and other aspects of Mexican society. However, due to government restrictions many of them left the country in the early 20th century.

Mexico’s northern regions have the greatest European population and admixture. In the northwest, the majority of the relatively small indigenous communities remain isolated from the rest of the population, and as for the northeast, the indigenous population was eliminated by early European settlers, becoming the region with the highest proportion of whites during the Spanish period. However, recent immigrants from southern Mexico have been changing, to some degree, its demographic trends. The White population of central Mexico, despite not being as numerous as in the north due to higher mixing, is ethnically more diverse, as there are large numbers of other European and Middle Eastern ethnic groups, aside from Spaniards. This also results in non-Iberian surnames (mostly French, German, Italian and Arab) being more common in central Mexico, especially in the country’s capital and in the state of Jalisco.

Indigenous Mexicans

Benito Juárez was the first President of Indigenous descent in Mexico.

The Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Languages recognizes 62 indigenous languages as “national languages” which have the same validity as Spanish in all territories in which they are spoken. According to the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Data Processing (INEGI), approximately 5.4% of the population speaks an indigenous language – that is, approximately half of those identified as indigenous. The recognition of indigenous languages and the protection of indigenous cultures is granted not only to the ethnic groups indigenous to modern-day Mexican territory, but also to other North American indigenous groups that migrated to Mexico from the United States in the nineteenth century and those who immigrated from Guatemala in the 1980s.

According to the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, or CDI in Spanish) and the INEGI (official census institute), there are 15.7 million indigenous people in Mexico, of many different ethnic groups, which constitute 14.9% of the population in the country. The number of indigenous Mexicans is judged using the political criteria found in the 2nd article of the Mexican constitution. The Mexican census does not report racial-ethnicity but only the cultural-ethnicity of indigenous communities that preserve their indigenous languages, traditions, beliefs, and cultures. In 2011 a large scale mitochondrial sequencing in Mexican Americans revealed 85 to 90% of mtDNA lineages of Native American origin, with the remainder having European (5-7%) or African ancestry (3-5%). Thus the observed frequency of Native American mtDNA in Mexican/Mexican Americans is higher than was expected on the basis of autosomal estimates of Native American admixture for these populations i.e. ~ 30-46%

The absolute indigenous population is growing, but at a slower rate than the rest of the population so that the percentage of indigenous peoples is nonetheless falling. The majority of the indigenous population is concentrated in the central and southern states, which are generally the least developed, and the majority of the indigenous population live in rural areas. Some indigenous communities have a degree of autonomy under the legislation of “usos y costumbres”, which allows them to regulate some internal issues under customary law.

According to the CDI, the states with the greatest percentage of indigenous population are: Yucatán, with 62.7%, Quintana Roo with 33.8% and Campeche with 32% of the population being indigenous, most of them Maya; Oaxaca with 58% of the population, the most numerous groups being the Mixtec and Zapotec peoples; Chiapas has 32.7%, the majority being Tzeltal and Tzotzil Maya; Hidalgo with 30.1%, the majority being Otomi; Puebla with 25.2%, and Guerrero with 22.6%, mostly Nahua people and the states of San Luis Potosí and Veracruz both home to a population of 19% indigenous people, mostly from the Totonac, Nahua and Teenek (Huastec) groups. The majority of the indigenous population is concentrated in the central and southern states.

According to the CDI, the states with the greatest percentage of indigenous population are:

- Yucatán, 62.7%

- Oaxaca, 58%

- Quintana Roo, 33.8%

- Chiapas, 32.7%

- Campeche, 32%

- Hidalgo, 30.1%

- Puebla, 25.2%

- Guerrero, 22.6%

- San Luis Potosí, 19.9%

- Veracruz, 19.2%

The category of “indigena” (indigenous) can be defined narrowly according to linguistic criteria including only persons that speak one of Mexico’s 62 indigenous languages, this is the categorization used by the National Mexican Institute of Statistics. It can also be defined broadly to include all persons who self identify as having an indigenous cultural background, whether or not they speak the language of the indigenous group they identify with. This means that the percentage of the Mexican population defined as “indigenous” varies according to the definition applied, cultural activists have referred to the usage of the narrow definition of the term for census purposes as “statistical genocide”.

Arab Mexicans

Carlos Slim is of Lebanese descent.

An Arab Mexican is a Mexican citizen of Arabic-speaking origin who can be of various ancestral origins. The vast majority of Mexico’s 1.1 million Arabs are from either Lebanese, Syrian, Iraqi, or Palestinian background. The interethnic marriage in the Arab community, regardless of religious affiliation, is very high; most community members have only one parent who has Arab ethnicity. As a result of this, the Arab community in Mexico shows marked language shift away from Arabic. Only a few speak any Arabic, and such knowledge is often limited to a few basic words. Instead the majority, especially those of younger generations, speak Spanish as a first language. Today, the most common Arabic surnames in Mexico include Nader, Hayek, Ali, Haddad, Nasser, Malik, Abed, Mansoor, Harb and Elias.

Arab immigration to Mexico started in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Roughly 100,000 Arabic-speakers settled in Mexico during this time period. They came mostly from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq and settled in significant numbers in Nayarit, Puebla, Mexico City and the Northern part of the country (mainly in the states of Baja California, Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Durango, as well as the city of Tampico and Guadalajara. The term “Arab Mexican” may include ethnic groups that do not in fact identify as Arab. During the Israel-Lebanon war in 1948 and during the Six-Day War, thousands of Lebanese left Lebanon and went to Mexico. They first arrived in Veracruz. Although Arabs made up less than 5% of the total immigrant population in Mexico during the 1930s, they constituted half of the immigrant economic activity.

Immigration of Arabs in Mexico has influenced Mexican culture, in particular food, where they have introduced Kibbeh, Tabbouleh and even created recipes such as Tacos Árabes. By 1765, Dates, which originated from the Middle East, were introduced into Mexico by the Spaniards. The fusion between Arab and Mexican food has highly influenced the Yucatecan cuisine. Another concentration of Arab-Mexicans is in Baja California facing the U.S.-Mexican border, esp. in cities of Mexicali in the Imperial Valley U.S./Mexico, and Tijuana across from San Diego with a large Arab American community (about 280,000), some of whose families have relatives in Mexico. 45% of Arab Mexicans are of Lebanese descent. The majority of Arab-Mexicans are Christians who belong to the Maronite Church, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Rite Catholic Churches. A scant number are Muslims and Jews of Middle Eastern origins.

Afro-Mexicans

Vincente Guerrero was an Afro-Mexican.

Afro-Mexicans are an ethnic group that predominate in certain areas of Mexico. Such as the Costa Chica of Oaxaca and the Costa Chica of Guerrero, Veracruz (e.g. Yanga) and in some towns in northern Mexico. The existence of blacks in Mexico is unknown, denied or diminished in both Mexico and abroad for a number of reasons: their small numbers, heavy intermarriage with other ethnic groups and Mexico’s tradition of defining itself as a “mestizaje” or mixing of European and indigenous. Mexico did have an active slave trade since the early Spanish period but from the beginning, intermarriage and mixed race offspring created an elaborate caste system. This system broke down in the very late Spanish period and after Independence the legal notion of race was eliminated. The creation of a national Mexican identity, especially after the Mexican Revolution, emphasized Mexico’s indigenous and European past actively or passively eliminating its African one from popular consciousness.

The majority of Mexico’s native Afro-descendants are Afromestizos, i.e. “mixed-race”. Individuals with significantly high amounts of African ancestry make up a very low percentage of the total Mexican population, the majority being recent black immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean and elsewhere in the Americas. As Mexico does not ask for race in its census, there is no exact number of Afro-descendants, with the most widely accepted number being 450,000 individuals of significant African descent. There has been a push by advocate groups for the government to include the question of whether an individual considers themselves to be black. This is seen as a stepping stone for the eventual goal of attaining constitutional recognition for the ethnic group. In 2015, as part of a national housing and population survey of 6.1 million households, a broad snapshot of the country in between the main censuses, the question has now been asked. The sample will allow for an official estimate of the total black population in Mexico and the results will be used to formulate the 2020 census (including what Afro-descendants prefer to be called, be it afromexicanos, negros, afrodescendientes etc.).

Asian Mexicans

Asian Mexicans make up less than 1% of the total population of modern Mexico, nonetheless they are a notable minority. Due to the historical and contemporary perception in Mexican society of what constitutes Asian culture (associated with the Far East rather than the Near East), Asian Mexicans are of East, South and Southeast Asian descent and Mexicans of West Asian descent are not considered to be part of the group.

Asian immigration began with the arrival of Filipinos to Mexico during the Spanish period. For two and a half centuries, between 1565 and 1815, many Filipinos and Mexicans sailed to and from Mexico and the Philippines as sailors, crews, slaves, prisoners, adventurers and soldiers in the Manila-Acapulco Galleon assisting Spain in its trade between Asia and the Americas. Also on these voyages, thousands of Asian individuals (mostly males) were brought to Mexico as slaves and were called “Chino”, which meant Chinese. Although in reality they were of diverse origins, including Japanese, Koreans, Malays, Filipinos, Javanese, Cambodians, Timorese, and people from Bengal, India, Ceylon, Makassar, Tidore, Terenate, and China. A notable example is the story of Catarina de San Juan (Mirra), an Indian girl captured by the Portuguese and sold into slavery in Manila. She arrived in New Spain and eventually she gave rise to the “China Poblana”.

These early individuals are not very apparent in modern Mexico for two main reasons: the widespread mestizaje of Mexico during the Spanish period and the common practice of Chino slaves to “pass” as Indios (the indigenous people of Mexico) in order to attain freedom. As had occurred with a large portion of Mexico’s black population, over generations the Asian populace was absorbed into the general Mestizo population. Facilitating this miscegenation was the assimilation of Asians into the indigenous population. The indigenous people were legally protected from chattel slavery, and by being recognized as part of this group, Asian slaves could claim they were wrongly enslaved. Asians, predominantly Chinese, became Mexico’s fastest-growing immigrant group from the 1880s to the 1920s, exploding from about 1,500 in 1895 to more than 20,000 in 1910.

1921 Census

The Mexican Government asked Mexicans about their perception of their own racial heritage. In the 1921 census, residents of the Mexican Republic were asked if they fell into one of the following categories:

- “Indígena pura” (of pure indigenous heritage)

- “Indígena mezclada con blanca” (of mixed indigenous and white heritage, the term mestizo itself wasn’t used by the government in this census)

- “Blanca” (of White or Spanish heritage)

- “Extranjeros sin distinción de razas” (Foreigners without racial distinction)

- “Cualquiera otra o que se ignora la raza” (Either other or chose to ignore the race)

- Pure indigenous heritage: 4,179,440 {29%}

- Mixed indigenous and white: 8,504,561 {60%}

- White or Spanish heritage: 1,404,718 (10%)

At the time the total population was 14,334,780. This was the last Mexican Census which asked individuals to self-identify themselves with a heritage other than Amerindian. However, the census had the particularity that, unlike racial/ethnic census in other countries, it was focused in the perception of cultural heritage rather than in a racial perception, leading to a good number of white people to identify with “Mixed heritage” due cultural influence.

| Federative Units | Mestizo Population (%) | Amerindian Population (%) | White Population (%) |

| Mexico | 60% | 29% | 10% |

| Aguascalientes | 66% | 16% | 17% |

| Baja California | 64% | 7% | 28% |

| Campeche | 41% | 43% | 15% |

| Coahuila | 79% | 10% | 11% |

| Colima | 68% | 26% | 6% |

| Chiapas | 36% | 47% | 16% |

| Chihuahua | 50% | 12% | 37% |

| Federal District | 55% | 18% | 26% |

| Durango | 79% | 10% | 11% |

| Guanajuato | 66% | 3% | 30% |

| Guerrero | 54% | 44% | 2% |

| Hidalgo | 51% | 39% | 9% |

| Jalisco | 56% | 16% | 27% |

| State of Mexico | 47% | 42% | 10% |

| Michoacan | 70% | 20% | 9% |

| Morelos | 61% | 35% | 4% |

| Nayarit | 66% | 18% | 15% |

| Nuevo Leon | 65% | 5% | 29% |

| Oaxaca | 28% | 69% | 2% |

| Puebla | 39% | 54% | 6% |

| Querétaro | 70% | 19% | 11% |

| Quintana Roo | 77% | 13% | 10% |

| San Luis Potosí | 62% | 30% | 7% |

| Sinaloa | 88% | 1% | 10% |

| Sonora | 40% | 13% | 46% |

| Tabasco | 70% | 15% | 15% |

| Tamaulipas | 69% | 13% | 17% |

| Tlaxcala | 42% | 54% | 3% |

| Veracruz | 47% | 35% | 17% |

| Yucatán | 44% | 43% | 13% |

| Zacatecas | 86% | 8% | 5% |

Today

| Racial and ethnic composition in Mexico – (Encyclopædia Britannica) | ||||

| Race | Percent of population | |||

| Mestizo | 65.0% | |||

| Amerindian | 17.5% | |||

| White | 16.5% | |||

| Other | 1.0% | |||

| Total | 100% | |||

Nowadays people of different ethnicities coexist under the same Mexican national identity, although discrimination due to skin color still exists. Ethnic relations in modern Mexico have grown out of the historical context of the arrival of Europeans, the subsequent Spanish period of cultural and genetic miscegenation within the frame work of the castas system, the revolutionary periods focus on incorporating all ethnic and racial group into a common Mexican national identity and the indigenous revival of the late 20th century. The resulting picture has been called “a peculiar form of multi-ethnic nationalism”. Very generally speaking ethnic relations can be arranged on an axis between the two extremes of European and Amerindian cultural heritage, this is a remnant of the Spanish caste system which categorized individuals according to their perceived level of biological mixture between the two groups. Additionally the presence of considerable portions of the population with partly African and Asian heritage further complicates the situation. Even though it still arranges persons along the line between indigenous and European, in practice the classificatory system is no longer biologically based, but rather mixes socio-cultural traits with phenotypical traits, and classification is largely fluid, allowing individuals to move between categories and define their ethnic and racial identities situationally.

Population genetics

The Mexican mestizo population is the most diverse of all the mestizo groups of Hispanic America, with its mestizos being either largely European or Amerindian rather than having a uniform admixture. In the 21st century, studies in Mexico by national Mexican institutes of Mexican genetic admixture have established that a high proportion of the Mexican population has predominately European ancestry. In some studies the population is shown to be majority European, comparable to South American countries in which a higher proportion of the population has traditionally been classified as European or ‘white.’ There is genetic asymmetry, with the direct paternal line predominately European and the maternal line predominately Amerindian. For instance, a 2006 study conducted by Mexico’s National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), which genotyped 104 samples, reported that mestizo Mexicans are 58.96% European, 35.05% “Asian” (primarily Amerindian), and 5.03% Other. According to a 2009 report by the Mexican Genome Project, which sampled 300 mestizos from six Mexican states and one indigenous group, the gene pool of the Mexican mestizo population was calculated to be 55.2% percent indigenous, 41.8% European, 1.0% African, and 1.2% Asian.

A 2012 study published by the Journal of Human Genetics Y chromosomes found the deep paternal ancestry of the Mexican mestizo population to be predominately European (64.9%), followed by Amerindian (30.8%) and Asian(1.2%). The European Y chromosome was more prevalent in the north and west (66.7-95%) and Native American ancestry increased in the center and southeast (37-50%), the African ancestry was low and relatively homogeneous (0-8.8%). The states that participated in this study where Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Durango, Guerrero, Jalisco, Oaxaca, Sinaloa, Veracruz and Yucatán. The largest amount of chromosomes found were identified as belonging to the haplo-groups from Western Europe, East Europe and Euroasia, Siberia and the Americas and Northern Europe with relatively smaller traces of haplogroups from Central Asia, South-east Asia, South-central Asia, Western Asia, The Caucasus, North Africa, Near East, East Asia, North-east Asia, South-west Asia and the Middle East. Also a study published in 2011 on Mexican Mitochondrial DNA found that maternal ancestry was predominately Native American (85-90%), with a minority having European (5-7%) or African (3-5%) mtDNA. Additional studies suggests a tendency relating a higher European admixture with a higher socioeconomic status and a higher Amerindian ancestry with a lower socioeconomic status: a study made exclusively on low income Mestizos residing in Mexico City found the mean admixture to be 0.590, 0.348, and 0.062 for Amerindian, European and African respectively whereas the European admixture increased to an average of around 70% on mestizos belonging to a higher socio-economical level.

Languages

Mexico is home to some of the world’s oldest writing systems such as Mayan Script. Maya writing uses logograms complemented by a set of alphabetical or syllabic glyphs and characters, similar in function to modern Japanese writing. Mexicans are linguistically diverse, with many speaking European languages as well as various Indigenous Mexican Languages. Spanish is spoken by approximately 92.17% of Mexicans as their first language making them the largest Spanish speaking group in the world followed by Colombia (45,273,925), Spain (41,063,259) and Argentina (40,134,425). Although the great majority speak Spanish de facto the second most populous language among Mexicans is English due to the regional proximity of the United States which calls for a bilingual relationship in order to conduct business and trade as well as the migration of Mexicans into that country who adopt it as a second language. Mexican Spanish is distinct in dialect, tone and syntax to the Peninsular Spanish spoken in Spain. It contains a large amount of loan words from indigenous languages, mostly from the Nahuatl language such as: “chocolate”, “tomate”, “mezquite”, “chile”, and “coyote”.

Mexico has no official de jure language, but as of 2003 it recognizes 62 indigenous Amerindian languages as “national languages” along with Spanish which are protected under Mexican National law giving indigenous peoples the entitlement to request public services and documents in their native languages. The law also includes other Amerindian languages regardless of origin, that is, it includes the Amerindian languages of other ethnic groups that are non-native to the Mexican national territory. As such, Mexico’s National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples recognizes the language of the Kickapoo who immigrated from the United States, and recognizes the languages of Guatemalan Amerindian refugees. The most numerous indigenous language spoken by Mexicans is Nahuatl which is spoken by 1.7% of the population in Mexico over the age of 5. Approximately 6,044,547 Mexicans (5.4%) speak an indigenous language according to the 2000 Census in Mexico. There are also Mexicans living abroad which speak indigenous languages mostly in the United States but their number is unknown.

Chipilo Venetian or Chipileño is a diaspora language currently spoken by the descendants of some five hundred 19th century Venetian immigrants to Mexico. The Venetians settled in the State of Puebla, founding the city of Chipilo. This Venetian variety is also spoken in other communities in Veracruz and Querétaro, places where the chipileños settled as well. Although the city of Puebla has grown so far as to almost absorb it, the town of Chipilo remained isolated for much of the 20th century. Thus, the Cipiłàn/chipileños, unlike other European immigrants that came to Mexico, did not blend into the Mexican culture and retained most of their traditions and their language. To this day, most of the people in Chipilo speak the Venetan or Venetian of their great-grandparents. The variant of the Venetan language spoken by the Cipiłàni/chipileñi is the northern Traixàn-Fheltrìn-Bełumàt. Surprisingly, it has been barely altered by Spanish, as compared to how the dialect of the northern Veneto has been altered by Italian. Given the number of speakers of Venetan, and even though the state government has not done so, the Venetan language has to be considered a minority language in the State of Puebla.

Culture

Mexican culture reflects the complexity of the country’s history through the blending of indigenous cultures and the culture of Spain, imparted during Spain’s 300-year colonization of Mexico. Exogenous cultural elements mainly from the United States have been incorporated into Mexican culture. The Porfirian era (el Porfiriato), in the last quarter of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century, was marked by economic progress and peace. After four decades of civil unrest and war, Mexico saw the development of philosophy and the arts, promoted by President Díaz himself. Since that time, as accentuated during the Mexican Revolution, cultural identity has had its foundation in the mestizaje, of which the indigenous (i.e. Amerindian) element is the core. In light of the various ethnicities that formed the Mexican people, José Vasconcelos in his publication La Raza Cósmica (The Cosmic Race) (1925) defined Mexico to be the melting pot of all races (thus extending the definition of the mestizo) not only biologically but culturally as well. This exalting of mestizaje was a revolutionary idea that sharply contrasted with the idea of a superior pure race prevalent in Europe at the time.

Literature

The literature of Mexico has its antecedents in the literatures of the indigenous settlements of Mesoamerica. The most well-known pre-hispanic poet is Nezahualcoyotl. Modern Mexican literature was influenced by the concepts of the Spanish colonialization of Mesoamerica. Outstanding writers and poets from the Spanish period include Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Bernardo de Balbuena and Juana Inés de la Cruz. In light of the various ethnicities that formed the Mexican people, José Vasconcelos in his publication La Raza Cósmica (The Cosmic Race) (1925) defined Mexico to be the melting pot of all races, biologically as well as culturally. Other writers include Alfonso Reyes, José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, Ignacio Manuel Altamirano, Carlos Fuentes, Octavio Paz (Nobel Laureate), Renato Leduc, Carlos Monsiváis, Elena Poniatowska, José Emilio Pacheco, Mariano Azuela (“Los de abajo”) and Juan Rulfo (“Pedro Páramo”). Bruno Traven wrote “Canasta de cuentos mexicanos”, “El tesoro de la Sierra Madre.”

Science

The National Autonomous University of Mexico was officially established in 1910, and the university become one of the most important institutes of higher learning in Mexico. UNAM provides world class education in science, medicine, and engineering. Many scientific institutes and new institutes of higher learning, such as National Polytechnic Institute (founded in 1936), were established during the first half of the 20th century. Most of the new research institutes were created within UNAM. Twelve institutes were integrated into UNAM from 1929 to 1973. In 1959, the Mexican Academy of Sciences was created to coordinate scientific efforts between academics.

In 1995 the Mexican chemist Mario J. Molina shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Paul J. Crutzen and F. Sherwood Rowland for their work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone. Molina, an alumnus of UNAM, became the first Mexican citizen to win the Nobel Prize in science. In recent years, the largest scientific project being developed in Mexico was the construction of the Large Millimeter Telescope (Gran Telescopio Milimétrico, GMT), the world’s largest and most sensitive single-aperture telescope in its frequency range. It was designed to observe regions of space obscured by stellar dust. The electronics industry of Mexico has grown enormously within the last decade. In 2007 Mexico surpassed South Korea as the second largest manufacturer of televisions, and in 2008 Mexico surpassed China, South Korea and Taiwan to become the largest producer of smartphones in the world. There are almost half a million (451,000) students enrolled in electronics engineering programs.

Well known Mexican Scientists include:

- Andrés Manuel del Río discovered the element vanadium

- José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez

- Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora

- Manuel Mondragón

- George Rosenkranz

- Mario Molina

- Alexander Balankin

- Rodolfo Neri

- Nora Volkow

Music

Mexican society enjoys a vast array of music genres, showing the diversity of Mexican culture. Traditional music includes Mariachi, Banda, Norteño, Ranchera and Corridos; on an everyday basis most Mexicans listen to contemporary music such as pop, rock, etc. in both English and Spanish. Mexico has the largest media industry in Hispanic America, producing Mexican artists who are famous in Central and South America and parts of Europe, especially Spain. Some well-known Mexican singers are Thalía, Luis Miguel, Fher Olvera, Alejandro Fernández, Julieta Venegas, Juan Gabriel, Marco Antonio Solís and Paulina Rubio. Mexican singers of traditional music are: Lila Downs, Susana Harp, Jaramar, GEO Meneses, Agustín Lara, Vicente Fernández and Alejandra Robles. Popular groups are Café Tacuba, Molotov and Maná, among others. Early well known singers and musicians were Cenobio Paniagua, Aniceto Ortega, Ángela Peralta, Silvestre Revueltas and Pedro Vargas. Since the early years of the 2000s (decade), Mexican rock has seen widespread growth both domestically and internationally. Mexico’s most famous rock star would be of Carlos Santana.

Cinema

Mexican films from the Golden Age in the 1940s and 1950s are the greatest examples of Hispanic American cinema, with a huge industry comparable to the Hollywood of those years. Mexican films were exported and exhibited in all of Hispanic America and Europe. Maria Candelaria (1944) by Emilio Fernández, was one of the first films awarded a Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1946, the first time the event was held after World War II. The famous Spanish-born director Luis Buñuel realized in Mexico, between 1947 to 1965 some of his master pieces like Los Olvidados (1949), Viridiana (1961) and El angel exterminador (1963). Famous actors and actresses from this period include María Félix, Pedro Infante, Dolores del Río, Jorge Negrete and the comedian Cantinflas. More recently, films such as Como agua para chocolate (1992), Cronos (1993), Y tu mamá también (2001), and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) have been successful in creating universal stories about contemporary subjects, and were internationally recognised, as in the prestigious Cannes Film Festival. Mexican directors Alejandro González Iñárritu (Amores perros, Babel, Birdman), Alfonso Cuarón (Children of Men, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Gravity), Guillermo del Toro (Pacific Rim), Carlos Carrera (The Crime of Father Amaro), and screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga are some of the most known present-day film makers. Other famous Mexican actors, actresses and filmmakers include:

- Salvador Toscano

- Emma Padilla

- Ramon Novarro

- Gilbert Roland

- Lupe Vélez

- Ricardo Montalban

- Anthony Quinn

- Guillermo del Toro

- Salma Hayek

Visual arts

Post-revolutionary art in Mexico had its expression in the works of renowned artists such as Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Rufino Tamayo, Federico Cantú Garza, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Juan O’Gorman. Diego Rivera, the most well-known figure of Mexican muralism, painted the Man at the Crossroads at the Rockefeller Center in New York City, a huge mural that was destroyed the next year because of the inclusion of a portrait of Russian communist leader Lenin. Some of Rivera’s murals are displayed at the Mexican National Palace and the Palace of Fine Arts. Others famous Mexican artists include:

- Miguel Cabrera

- Claudio Linati

- Casimiro Castro

- Agustín Arrieta

- Juan Cordero

- José María Velasco Gómez

- Guillermo Kahlo

- Manuel Felguérez

Architecture

For the artistic relevance of many of Mexico’s architectural structures, including entire sections of pre-hispanic and colonial cities, have been designated World Heritage. The country has the first place in number of sites declared World Heritage Site by UNESCO in the Americas. Many of Mexico’s well known Architects include:

- Ruth Rivera Marín

- Juan O’Gorman

- Pedro Ramírez Vázquez

- Luis Barragán

- Abraham Zabludovsky

- Fernando González Gortázar

- Fernando Romero

Notable Mexicans and Historical Figures

- Moctezuma II

- Miguel Hidalgo

- Ignacio Allende

- José María Morelos

- Agustín de Iturbide

- Vicente Guerrero

- Guadalupe Victoria

- Santa Anna

- Benito Juárez

- Porfirio Diaz

- Francisco I. Madero

- Emiliano Zapata

- Pancho Villa

- Álvaro Obregón

- Venustiano Carranza

- Plutarco Elías Calles

- Lázaro Cárdenas

Well known Mexican Sport Figures

- Kid Azteca

- Pedro Rodríguez

- Javier Aguirre

- Ana Guevara

- Fernando Valenzuela

- Hugo Sánchez

- Adrián Fernández

- Julio César Chávez

- Cuauhtémoc Blanco

- Guillermo Gracida, Jr.

- Rafael Márquez

- Lorena Ochoa

- Javier Hernández

- Sergio Pérez

Notable Mexican Business Leaders

- Carlos Slim

- Ricardo Salinas Pliego

- María Asunción Aramburuzabala

- Alberto Baillères

- Alfredo Harp Helú

- Angélica Fuentes

Religion

Religion in Mexico (2010)

- Catholic Church (82.7%)

- Other Christians (9.7%)

- Other religions (2.9%)

- Non-religious (4.7%)

Mexico has no official religion, and the Constitution of 1917 imposed limitations on the church and sometimes codified state intrusion into church matters. The government does not provide financial contributions to the church, nor does the church participate in public education. However, Christmas is a national holiday and every year during Easter and Christmas all schools in Mexico, public and private, send their students on vacation. In 1992, Mexico lifted almost all restrictions on the religions, including granting all religious groups legal status, conceding them limited property, and lifting restrictions on the number of priests in the country. Until recently, priests did not have the right to vote, and even now they cannot be elected to public office. The Catholic Church is the dominant religion in Mexico, with about 82.7% of the population as of 2010. In recent decades the number of Catholics has been declining, due to the growth of other Christian denominations (especially various Protestant churches and Mormonism), which now constitute 9.7% of the population, and non-Christian religions. Despite this, conversion to non-Catholic denominations has been considerably slower than in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. An estimated 2 to 5 million Mexicans (~2% to ~4.5%) adhere to the Santa Muerte Religion, though most of them continue to declare themselves as members of the Catholic Church. Movements of return and revival of the indigenous Mesoamerican religions (Mexicayotl, Toltecayotl) have also appeared in recent decades. Islam and Buddhism have both made limited inroads, through immigration and conversion.