November 3, 2016 – Hard to believe we have been doing this for 7 years and counting, now starting season 8. 36 tours, almost 400 Rvers and approximately 150,000 km driving on Baja. Lisa and I have lead 23 tours, almost 100,000 km on Baja, no wonder we are tired at the end of each Baja season. This season we had made some major and minor changes to our tour, some by choice, others not. We will no longer stay at the Baja Fiesta Restaurant (dinner yes) or Palapa 206. We will now be stopping in Los Barriles, not Los Cabos, as the last RV Park “Villa Serena” closed effective October 1st, 2016. Other big changes for us this season is the loss of my best Mexican friend Antonio Residendiz who passed away suddenly on Easter Sunday this year when we were traveling on the Mexico mainland. On the brighter side we added our friends Mike & Kelly from Kansas as Wagon Masters this season. We did say goodbye to Dom & Dianne after 3 seasons, thank you for your service to Baja Amigos, you were wonderful.

November 3, 2016 – Hard to believe we have been doing this for 7 years and counting, now starting season 8. 36 tours, almost 400 Rvers and approximately 150,000 km driving on Baja. Lisa and I have lead 23 tours, almost 100,000 km on Baja, no wonder we are tired at the end of each Baja season. This season we had made some major and minor changes to our tour, some by choice, others not. We will no longer stay at the Baja Fiesta Restaurant (dinner yes) or Palapa 206. We will now be stopping in Los Barriles, not Los Cabos, as the last RV Park “Villa Serena” closed effective October 1st, 2016. Other big changes for us this season is the loss of my best Mexican friend Antonio Residendiz who passed away suddenly on Easter Sunday this year when we were traveling on the Mexico mainland. On the brighter side we added our friends Mike & Kelly from Kansas as Wagon Masters this season. We did say goodbye to Dom & Dianne after 3 seasons, thank you for your service to Baja Amigos, you were wonderful.

We had a very busy wine & beer tour season with South Fraser Shuttles and tour, over 45 Wine Tours from April 15 to September 30. We purchased a 12 seater bus which allowed us to meet the growing demand for our service. We have kept that vehicle insured and continue to operate the company in our absence, the requests for tours keep rolling in. I am confident next season will be busier then ever. Who ever thought this “fill in work” in our off season from Baja would ever grow to this. Many thanks to our friends Terry & Lee from Modesto who took us on our first Wine Tour in 2010 in California when we stopped to see them. They planted the seed for sure. This year we left home on Tuesday, October 11, after Thanksgiving, the skies were blue with sunshine forecast for our trip south. As always we are anxious to depart after a long summer and look forward to meeting with old Baja friends on the way down. Our first, the Walmart in Woodburn, our the second stop, the Friendly RV Park in Weed, CA, where for some reason everyone is always happy and the take-out restaurants busy as beavers.

We had a very busy wine & beer tour season with South Fraser Shuttles and tour, over 45 Wine Tours from April 15 to September 30. We purchased a 12 seater bus which allowed us to meet the growing demand for our service. We have kept that vehicle insured and continue to operate the company in our absence, the requests for tours keep rolling in. I am confident next season will be busier then ever. Who ever thought this “fill in work” in our off season from Baja would ever grow to this. Many thanks to our friends Terry & Lee from Modesto who took us on our first Wine Tour in 2010 in California when we stopped to see them. They planted the seed for sure. This year we left home on Tuesday, October 11, after Thanksgiving, the skies were blue with sunshine forecast for our trip south. As always we are anxious to depart after a long summer and look forward to meeting with old Baja friends on the way down. Our first, the Walmart in Woodburn, our the second stop, the Friendly RV Park in Weed, CA, where for some reason everyone is always happy and the take-out restaurants busy as beavers.

Day 3 and we were headed to Placerville, CA to visit Steve & Dale that we met years ago on Playa Requeson, one of many beaches in the Bay of Concepcion. The trip was going very smoothly except for a molar that decided to abscess the day we crossed the US Border. Thankfully Dale made arrangements for a dentist appointment the day after we arrived. For those that do not know, I loath the dentist, as I had a really crappy dentist in Burnaby when I was young, Dr McAllister as I recall. After X Rays, an examine and consult it was decided a root canal and crown were not possible, the tooth had to be yanked. Oh good! 3 hours later and a small piece of the route broken off and left in my jaw I was released with a pain medication and assorted meds prescribed. After a great stay with Steve & Dale, which included a dinner with the neighbours, a tour of Placerville Old Town, a lengthy drive and stay by Steve to the dentist we headed off to Terry & Lee’s house in Modesto, my dental problems not healing as quickly as expected. Thank you Dale & Steve for being such great hosts, we are envious of your manufactured home which we see in our future one day in the Okanagan.

Day 3 and we were headed to Placerville, CA to visit Steve & Dale that we met years ago on Playa Requeson, one of many beaches in the Bay of Concepcion. The trip was going very smoothly except for a molar that decided to abscess the day we crossed the US Border. Thankfully Dale made arrangements for a dentist appointment the day after we arrived. For those that do not know, I loath the dentist, as I had a really crappy dentist in Burnaby when I was young, Dr McAllister as I recall. After X Rays, an examine and consult it was decided a root canal and crown were not possible, the tooth had to be yanked. Oh good! 3 hours later and a small piece of the route broken off and left in my jaw I was released with a pain medication and assorted meds prescribed. After a great stay with Steve & Dale, which included a dinner with the neighbours, a tour of Placerville Old Town, a lengthy drive and stay by Steve to the dentist we headed off to Terry & Lee’s house in Modesto, my dental problems not healing as quickly as expected. Thank you Dale & Steve for being such great hosts, we are envious of your manufactured home which we see in our future one day in the Okanagan.

We arrived in Modesto to great weather and a continuing sore tooth. After a couple of days we all headed off to Hemet and the Golden Village Palms RV Resort for a week, a great deal at $149 for the week. This park has all the bells and whistles including 3 pools, 3 hot tubs, 6 pool tables, a fantastic exercise room, a remarkable laundry and so much more. Of course, I went to see a dentist the day after we arrived, yes now I had what is referred to as dry socket. Oh good! Our time in Hemet went fast, lots of fun with Lee & Terry, in the pools, playing pool, Mexican Train and more. Went to see the dentist again the day before we departed, green light all was good!

Next we booked into the Rancho Jurupa County Park and Campground near Riverside, CA. This was not the Golden Village Palms in Hemet, we went from the Penthouse to the Outhouse, as they say. The Park it self was very nice, as was the premium RV Park “Cottonwood Campground”, unfortunately this was booked up. We were relegated to the “Lakeview Campground”, which was rather dumpy, and appeared to be laid out by someone who excelled in random thinking. No particular rhyme or reason where and how the sites were placed; just locating our site was an adventure all to itself. Next to flair up was my gout in my right foot, this lasted about 4 days and was very painful. Having said that we made the best of our stay and time with Terry & Lee. Lots of looking around Riverside and the local area, caught a softball game with one of their grandkids, London, who plays for CBU (California Baptist University). We also watched some World Series baseball, movies played a round of mini-golf and as always, did some shopping. Despite Terry & Lee’s efforts we had yet to find a Paddleboard Leash before we headed south to Oak Creek where we start in earnest to prepare for our 38 Day fall Baja tour. Thank you Terry & Lee for your company and hospitality over the past couple of weeks. We look forward to seeing you again sooner than later.

We arrived at Oak Creek safe and sound and was able to get in some hot tub and pool time. We caught the World Series Game 7 on the big screen TV last night, well past my bed time, great game. Lisa & I have a meeting scheduled with Geoff from Baja Bound this morning and so the Baja Amigos season begins.

Did you know?

Did you know?

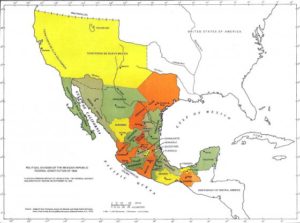

Alta California (aka Upper California), founded in 1769 by Gaspar de Portolá, was a polity of New Spain and after the Mexican War of Independence in 1822, a territory of Mexico. The region included all of the modern states of California, Nevada, and Utah, and parts of Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico.

Neither Spain nor Mexico ever colonized the area beyond the southern and central coastal area of present-day California, so they never exerted any effective control beyond Sonoma in the north or the California Coast Ranges in the west. Most of interior areas such as the Central Valley and the deserts of California remained in de facto possession of indigenous peoples until later in the Mexican era when more inland land grants were made, and especially after 1841 when overland immigrants from the United States began to settle inland areas. Large areas east of the Sierra Nevada and San Gabriel Mountains were claimed to be part of Alta California, but were never colonized. To the southeast, beyond the deserts and the Colorado River, lay the Spanish settlements in Arizona.

Alta California ceased to exist as an administrative division separate from Baja California in 1836, when the Siete Leyes constitutional reforms in Mexico re-established Las Californias as a unified department. The areas formerly comprising Alta California were ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War in 1848. Two years later, California joined the union as the 31st state. Other parts of Alta California became all or part of the later U.S. states of Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming.

The Spanish originally explored the coastal area of Alta California by sea beginning in the 16th century and considered the area a domain of the Spanish monarchy. During the following two centuries there were various plans to settle the area, none of which were effectively carried out. These included: (a) Sebastián Vizcaíno’s expedition in 1602–03 preparatory to colonization planned for 1606–07 which was cancelled in 1608; (b) plans promoted by Father Eusebio Kino who missionized the Pimería Alta from 1687 until his death in 1711, (c) plans by Juan Manuel de Oliván Rebolledo in 1715 resulting in a decree in 1716 for extension of the conquest (of Baja California) which came to nothing; (d) Juan Bautista de Anssa’s proposed expedition from Sonora in 1737; (e) a plan by the Council of the Indies in 1744; (f) and the one by Don Fernando Sánchez Salvador, who researched the earlier proposals and suggested the area of the Gila and Colorado Rivers as the locale for forts or presidios preventing the French or the English from “occupying Monterey and invading the neighboring coasts of California which are at the mouth of the Carmel River.”

Unfortunately for the Spanish Alta California was not easily accessible from New Spain: land routes were cut off by deserts and often hostile Native populations and sea routes ran counter to the southerly currents of the distant northeastern Pacific. Ultimately, New Spain did not have the economic resources nor population to settle such a far northern outpost. Spanish interest in colonizing Alta California was revived under the visita of José de Gálvez as part of his plans to completely reorganize the governance of the Interior Provinces and push Spanish settlement further north. In subsequent decades, news of Russian colonization and maritime fur trading in Alaska, and the 1768 naval expedition of Pyotr Krenitsyn and Mikhail Levashev, in particular, alarmed the Spanish government and served to justify Gálvez’s vision. To ascertain the Russian threat a number of Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest were launched. In preparation for settlement of Alta California, the northern, mainland region of Las Californias was granted to Franciscan missionaries to convert the Native population to Catholicism, following a model that had been used for over a century in Baja California. The Spanish Crown funded the construction and subsidized the operation of the missions, with the goal that the relocation, conversion and enforced labor of Native people would bolster Spanish rule.

The first Alta California mission and presidio were established by the Franciscan friar Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolá in San Diego in 1769. The following year, 1770, the second mission and presidio were founded in Monterey. In 1773 a boundary between the Baja California missions (whose control had been passed to the Dominicans) and the Franciscan missions of Alta California was set by Francisco Palóu. The missionary effort coincided with the construction of presidios and pueblos, which were to be manned and populated by Hispanic people. The first pueblo founded was San José in 1777, followed by Los Ángeles in 1781. (Branciforte, founded in 1797, failed to maintain enough settlers to be granted pueblo status.)

Spanish rule

By law, mission land and property were to pass to the indigenous population after a period of about ten years, when the natives would become Spanish subjects. In the interim period, the Franciscans were to act as mission administrators who held the land in trust for the Native residents. The Franciscans, however, prolonged their control over the missions even after control of Alta California passed from Spain to independent Mexico, and continued to run the missions until they were secularized, beginning in 1833. The transfer of property never occurred under the Franciscans.

As the number of Spanish settlers grew in Alta California, the boundaries and natural resources of the mission properties became disputed. Conflicts between the Crown and the Church and between Natives and settlers arose. State and ecclesiastical bureaucrats debated over authority of the missions. The Franciscan priests of Mission Santa Clara de Asís sent a petition to the governor in 1782 which stated that the Mission Indians owned both the land and cattle and represented the Ohlone against the Spanish settlers in nearby San José. The priests reported that Indians’ crops were being damaged by the pueblo settlers’ livestock and that the settlers’ livestock was also “getting mixed up with the livestock belonging to the Indians from the mission” causing losses. They advocated that the Natives owned property and had the right to defend it.

In 1804, due to the growth of the Spanish population in new northern settlements, the province of Las Californias was divided just south of San Diego, following mission president Francisco Palóu’s division between the Dominican and Franciscan jurisdictions. Governor Diego de Borica is credited with defining Alta (upper) and Baja (lower) California’s official borders. The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, between the United States and Spain, established the northern limit of Alta California at latitude 42°N, which remains the boundary between the states of California, Nevada and Utah (to the south) and Oregon and Idaho (to the north) to this day. Mexico won independence in 1822, and Alta California became a territory of Mexico.

Ranchos of California

The Spanish and later Mexican governments rewarded retired soldados de cuera with large land grants, known as ranchos, for the raising of cattle and sheep. Hides and tallow from the livestock were the primary exports of California until the mid-19th century. The construction, ranching and domestic work on these vast estates was primarily done by Native Americans, who had learned to speak Spanish and ride horses. Unfortunately, a large percentage of the population of Native Californians died from European diseases. Under Spanish and Mexican rule the ranchos prospered and grew. Rancheros (cattle ranchers) and pobladores (townspeople) evolved into the unique Californio culture.

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821 upon conclusion of the decade-long Mexican War of Independence. As the successor state to the Viceroyalty of New Spain, Mexico automatically included the provinces of Alta California and Baja California as territories. With the establishment of a republican government in 1823, Alta California Territory, like many northern territories, was not recognized as one of the constituent States of Mexico because of its small population. The 1824 Constitution of Mexico refers to Alta California as a “territory”. In 1836, Mexico repealed the 1824 federalist constitution and adopted a more centralist political organization (under the Siete Leyes) that reunited Alta and Baja California in a single California Department (Departamento de las Californias). The change, however, had little practical effect in far-off Alta California. The capital of Alta California Territory remained Monterey, as it had been since the 1769 Portola expedition first established an Alta California government, and the local political structures were unchanged. The 1824 constitution was restored in 1846.

A more important development was increasing resentment of appointed governors sent from distant Mexico City, who came with little knowledge of local conditions and concerns. Also, laws imposed by the central government without much consideration of local conditions, such as the Mexican secularization act of 1833, caused friction between governors and the people. The friction came to a head in 1836, when Monterey-born Juan Bautista Alvarado led a revolt and seized the governorship from Nicolás Gutiérrez. Alvarado’s actions began a period of de facto home rule, in which the weak and fractious central government was forced to allow more autonomy in its most distant department. Other Californio governors followed, including Carlos Antonio Carrillo, Alvarado himself for a second time, and Pío Pico. The last non-Californian governor, Manuel Micheltorena, was driven out after another rebellion in 1845. Micheltorena was replaced by Pío Pico, last Mexican governor of California, who served until 1846.

Mexican–American War

In the final decades of Mexican rule, American and European immigrants arrived and settled in Alta California. Those in Southern California mainly settled in and around the established coastal settlements and tended to intermarry with the Californios. In Northern California, they mainly formed new settlements further inland, especially in the Sacramento Valley, and these immigrants focused on fur-trapping and farming and kept apart from the Californios.

In 1846, following reports of the annexation of Texas to the United States, American settlers in inland Northern California formed an army, captured the Mexican garrison town of Sonoma, and declared independence there as the California Republic. At the same time, the United States and Mexico had gone to war, and forces of the United States Army and Navy entered into Alta California and overpowered the Mexican garrison and Californio militia units. The forces of the California Republic abandoned their independence and assisted the United States forces after their arrival. The California Republic was never recognized by any nation, and existed for less than one month, but its flag (the “Bear Flag”) survives as the flag of the State of California.

In southern California, the Californios formed defensive units, which were victorious in the Siege of Los Angeles, the Battle of San Pasqual and the Battle of Domínguez Rancho. But subsequent encounters, the battles of Río San Gabriel and La Mesa, were indecisive. The southern Californios formally surrendered with the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847. After twenty-seven years in independent Mexico, California was ceded to the United States in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The United States paid Mexico fifteen million dollars for the total lands ceded.