April 10, 2016 – We are now sitting in Pendleton, Oregon at the Walmart on the last leg of our journey home. We will arrive in West Kelowna late this afternoon to see our granddaughter Sophie Grace for the first time, wow this has taken a long time.

Final days of our tour

Saturday, March 26 we headed to Chapala in the morning where there were lots of activities planned, markets and shops open everywhere. We had a good walkabout and left about noon which was good as there was much more traffic. We had a Pot Luck for dinner and played Mexican Train, Janice the novice was the winner, sometimes it happens that way. Our last day on Easter Sunday brunch hosted by Roland & Janice, which was tasty for sure. Later the gang hit the pool later, no more excursions planned. By the afternoon lots of Mexican families have left and the campground was nearly deserted of locals.

Next up was our 542 km (almost 400 miles) drive to Mazatlan, Sinaloa. Mike & Kelly were in lead and yes we had a couple of glitches early on. First the entrance to northbound Periferico was closed which caused just a little delay as we need to find a returno, then the last 80 km of 15D Cuota closed by police, which was annoying because we had just paid a hefty toll to be on it and this made the last bit of our long day, longer. We landed at the Punta Cerritos RV Park late in the afternoon, at first they only had two spots available, the after the others got parked another spot (#5) became available, waterfront near the pool. That worked out well. We had planned for dinner at 6pm with Eric & Sandra (Surrey friends who winter at a nearby Condo) at Roy’s Restaurant in the plaza next to the RV Park. Eric recommended Los Cerritos campground as the meeting place was next door. Dinner was good and we all had fun catching up on our respective time in Mexico. The next day Lisa and I walked down to the beachfront condo Eric & Sandra were staying at. Great view, nice beach, wonderful pool and a very nice apartment. Eric goes boogey boarding daily and a swim in the pool, what a great way to sit out January, February and March in Surrey each year. After our visit we all walked up the beach back to the RV Park. Spent the remainder of the day poolside and had a surprise visit from Paul Beddows, my Caravans de Mexico buddy. He was with some members of his group and scheduled to be out of Mexico on April 1. Later the gang all went for dinner at the “Bruja” Restaurant, a short walk around the corner and down the street on the ocean. The Musician was pretty good, the clown kinda creepy, the food was ok.

Day Next morning off to El Fuerte and our Copper Canyon adventure. The drive was uneventful and we arrived at our destination in the afternoon at the Bugamville Motel & Campground. Our Guide, Gabriel and his gal, Fran arrived shortly afterwards. We had a “Happy Hour” did introductions, then off to bed, our 7:30 am start would come early. The next day we also learned how many no-seeim bites we all had from the grass at the campground, itchy itchy. Out local transport arrived and we were off to meet the train at the station under sunny skies.

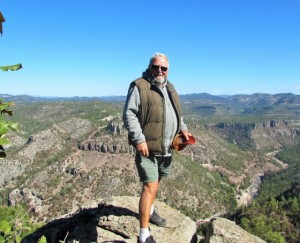

The Copper Canyon is one of Mexico’s most spectacular adventures! The preferred way to enjoy this scenic wonderland is via the Copper Canyon Train, completed in 1961, which departs Los Mochis twice a day headed for Chihuahua, we had 1st class seats. The canyon is the result of more than 60 million years of erosion, and covers an area four times as large as the Grand Canyon in the United States. The train ride includes 39 bridges and 87 tunnels (one of which is over a mile long!), and at its peak reaches an altitude of 8,056 feet above the Sea of Cortez. Actual canyon elevations run as high as 9,500 feet above sea level, while the surrounding mountains rise to over 12,000 feet! The other fun facts; the Copper Canyon (Spanish: Barrancas del Cobre) is a group of canyons consisting of six distinct canyons in the Sierra Madre Occidental in the southwestern part of the state of Chihuahua in northwestern Mexico. The overall canyon system is larger and portions are deeper than the Grand Canyon in Arizona. The canyons were formed by six rivers that drain the western side of the Sierra Tarahumara (a part of the Sierra Madre Occidental). All six rivers merge into the Rio Fuerte and empty into the Gulf of California. The walls of the canyon are a copper/green color, which is where the name originates.

The train ride was nothing less than spectacular as we ascended from 100m (300’) to almost 2800m (8000’). Unfortunately, our train ride was cut short as the local farmers erected a blockade on the tracks and we disembarked at Diversadero, 40 or so km (25 miles) before our destination at Creel. We jumped on a local bus arranged by the railway for the rest of the journey. Very different looking country because of the firs and pines, no surprise logging is the main industry in these parts. On arrival and checking into our Hotel, Gabriel & Fran hosted a “Happy Hour”, then we had dinner with entertainment, this was lots of fun. The next day we toured many Tarahumara communities. The Copper Canyon traditional inhabitants are the Tarahumara or Rarámuri. The Rarámuri or Tarahumara are a Native American people of northwestern Mexico who are renowned for their long-distance running ability. Living in the canyons, they travel great vertical distances, which they often do by running nonstop for hours. Originally inhabitants of much of the state of Chihuahua, the Rarámuri retreated to the high sierras and canyons such as the Copper Canyon in the Sierra Madre Occidental on the arrival of Spanish explorers in the 16th century. The area of the Sierra Madre Occidental which they now inhabit is often called the Sierra Tarahumara because of their presence.

Current estimates put the population of the Rarámuri in 2006 at between 50,000 and 70,000 people. Most still practice a traditional lifestyle, inhabiting natural shelters such as caves or cliff overhangs, as well as small cabins of wood or stone. Staple crops are corn and beans; however, many of the Rarámuri still practice transhumance, raising cattle, sheep, and goats. Almost all Rarámuri migrate in some form or another in the course of the year. Many Rarámuri reside in the cooler, mountainous regions during the hot summer months and migrate deeper into the canyons in the cooler winter months, where the climate is more temperate. Their survival strategies have been to occupy areas that are too remote for city people, way off-the-beaten-path, to remain isolated and independent, so as to avoid losing their culture. Tourism is a growing industry for Copper Canyon, but the acceptance of it is debated in the local communities. Some communities accept government funding for building roads, restaurants and lodging to make the area attractive for tourists. Many other groups of Rarámuri maintain their independence by living in areas that are as far away from city life as possible. Their way of life is protected by the mountainous landscape. The Tarahumara language belongs to the Uto-Aztecan family. Although it is in decline under pressure from Spanish, it is still widely spoken.

Creel has a very different feel and look than most Mexican towns, a combination of altitude, industry and the Tarahumara I suspect. Our final day in Creel was mostly about experiencing different viewpoints of the canyon. This include a Cable Car ride that was breathtaking in all aspects. Some of the group had seen the Zip Line and were keen to try it. All that ended when we witnessed a participant not make it to the end of the line because of high winds, they stopped short and had to be rescued, which of course did add some extra excitement. We learned in the morning that the blockade was over and the trains were running, good news as we were not looking forward to a 16-hour bus ride back to El Fuerte. We were returned to Diversadero as scheduled to catch the train which arrived on schedule. Later that evening our local transport picked us up at the Train Station and returned us to our RVs at about 8:00 pm. The next morning, we said our goodbyes to Gabriel & Fran and headed off to Guaymas, Sonora.

We arrived in the early afternoon to the Cortez Hotel on beach, kinda reminded me of Hotel Serenidad only older. We hit the pool and later had dinner in the Hotel Restaurant and reminisced about our Mexican Adventure. Day 89 and the next day we said our goodbyes. The Kansans were headed to the Nogales crossing, Lisa and I to Santa Ana. We had breakfast and left about an hour after the others. Our destination was an RV Park called Punta Vista, owned and operated by Edgar and Anna. We first met Mike, a New Yorker who has been travelling in Mexico for years. He was so impressed with all our stickers he donated a bag full that he had been collecting for some time. Next we met Edgar, a Mexican married to an American, Anna. He sure had an interesting life story, unfortunately Anna was not feeling that good and did not come out of the house.

Next day before 7:00 am we were off to Lukeville, AZ but first a stop at Pitiquito to turn in the Vehicle Import Stickers and our $400 USD Cash deposit, we arrived at 8:00 am, we think they just opened, 20 minutes and we were on our way, Jose! At the Lukeville crossing only 3 cars in front of us. The Border Officer very friendly asked some simple straight forward questions, “have a safe trip home”, no AG inspection which is routine at Tecate crossing. On we headed for Quartzsite, AZ and the Holiday Palms RV Park after arriving we made a few calls including to our friends from Modesto, CA Terry & Lee. As it turned out they were headed to Vegas so we agreed to meet them there. They had traveled to Southeast Asia at the same time as we did our Mexican tour, so we thought it would be a good time to catch up and swap stories. After leaving Las Vegas we headed for Wells, NV and on a body break who showed up but Darryl & Jan who had been on our February 2013 Baja tour, it was good to see them for sure. When we arrived in Wells we met Chris & Jeannie, our friends from Mulege at the gas pumps, what a small world.

Did you know?

The Mexican peso (sign: $; code: MXN) is the currency of Mexico. Modern peso and dollar currencies have a common origin in the 15th–19th century Spanish dollar, most continuing to use its sign, “$”. The Mexican peso is the 8th most traded currency in the world, the third most traded currency originating from the Americas (after the United States dollar and Canadian dollar), and the most traded currency originating from Latin America. The current ISO 4217 code for the peso is MXN; prior to the 1993 revaluation (see below), the code MXP was used. The peso is subdivided into 100 centavos, represented by “¢”. As of February 25, 2016, the peso’s exchange rate was $20.04 per Euro and $18.13 per U.S. dollar.

Etymology

The name was originally used in reference to pesos oro (gold weights) or pesos plata (silver weights). The literal English translation of the Spanish word peso is weight.

History – First Peso

The peso was originally the name of the eight-real coins issued in Mexico by Spain. These were the so-called Spanish dollars or pieces of eight in wide circulation in the Americas and Asia from the height of the Spanish Empire until the early 19th century (the United States in fact accepted the Spanish dollar as legal tender until the Coinage Act of 1857). In 1863, the first issue was made of coins denominated in centavos, worth one hundredth of the peso. This was followed in 1866 by coins denominated “one peso”. Coins denominated in reales continued to be issued until 1897. In 1905, the gold content of the peso was reduced by 49.3% but the silver content of the peso remained initially unchanged (subsidiary coins were debased). However, from 1918 onward, the weight and fineness of all the silver coins declined, until 1977, when the last silver 100-peso coins were minted.

Second Peso

Throughout most of the 20th century, the Mexican peso remained one of the more stable currencies in Latin America, since the economy did not experience periods of hyperinflation common to other countries in the region. However, after the Oil Crisis of the late 1970s, Mexico defaulted on its external debt in 1982, and as a result the country suffered a severe case of capital flight, followed by several years of inflation and devaluation, until a government economic strategy called the “Stability and Economic Growth Pact” (Pacto de estabilidad y crecimiento económico, PECE) was adopted under President Carlos Salinas. On January 1, 1993 the Bank of Mexico introduced a new currency, the nuevo peso (“new peso”, or MXN), written “N$” followed by the numerical amount. One new peso, or N$1.00, was equal to 1000 of the obsolete MXP pesos. On January 1, 1996, the modifier nuevo was dropped from the name and new coins and banknotes – identical in every respect to the 1993 issue, with the exception of the now absent word “nuevo” – were put into circulation. The ISO 4217 code, however, remained unchanged as MXN.

Thanks to the stability of the Mexican economy and the growth in foreign investment, the Mexican peso is now among the 15 most traded currency units in recent years. Since the late 1990s the peso has traded at about 9 to 15 pesos per U.S. dollar.

Use outside Mexico

The Spanish dollar or Mexican peso was widely used in the early United States. By a decree of July 6, 1785, the value of the United States dollar was set to approximately match the Spanish dollar, both of which were based on the weight of silver in the coins. The first U.S. dollar coins were not issued until April 2, 1792, and the peso continued to be officially recognized and used, along with other foreign coins, until February 21, 1857. In Canada, it remained legal tender, along with other foreign silver coins, until 1854 and continued to circulate beyond that date. The Mexican peso also served as the model for the Straits dollar (now the Singapore/Brunei Dollar), the Hong Kong dollar, the Japanese yen and the Chinese yuan. The term Chinese yuan refers to the round Spanish dollars, Mexican pesos and other 8 reales silver coins which saw use in China during the 19th and 20th century. The Mexican peso was also briefly legal tender in 19th century Siam, when government mints were unable to accommodate a sudden influx of foreign traders, and was exchanged at a rate of three pesos to one Thai baht.

Coins – 19th century

The first coins of the peso currency were 1 centavo pieces minted in 1863. Emperor Maximilian, ruler of the Second Mexican Empire from 1864–1867, minted the first coins with the legend “peso” on them. His portrait was on the obverse, with the legend “Maximiliano Emperador;” the reverse shows the imperial arms and the legends “Imperio Mexicano” and “1 Peso” and the date. They were struck from 1866 to 1867. The New Mexican republic continued to strike the 8 reales piece, but also began minting coins denominated in centavos and pesos. In addition to copper 1 centavo coins, silver (.903 fineness) coins of 5, 10, 25 and 50 centavos and 1 peso were introduced between 1867 and 1869. Gold 1, 2½, 5, 10 and 20-peso coins were introduced in 1870. The obverses featured the Mexican ‘eagle’ and the legend “Republica Mexicana.” The reverses of the larger coins showed a pair of scales; those of the smaller coins, the denomination. One-peso coins were made from 1865 to 1873, when 8 reales coins resumed production. In 1882, cupro-nickel 1, 2 and 5 centavos coins were issued but they were only minted for two years. The 1 peso was reintroduced in 1898, with the Phrygian cap, or liberty cap design being carried over from the 8 reales.

20th century

In 1905 a monetary reform was carried out in which the gold content of the peso was reduced by 49.36% and the silver coins were (with the exception of the 1 peso) reduced to token issues. Bronze 1 and 2 centavos, nickel 5 centavos, silver 10, 20 and 50 centavos and gold 5 and 10 pesos were issued. In 1910, a new peso coin was issued, the famous Caballito, considered one of the most beautiful of Mexican coins. The obverse had the Mexican official coat of arms (an eagle with a snake in its beak, standing on a cactus plant) and the legends “Estados Unidos Mexicanos” and “Un Peso.” The reverse showed a woman riding a horse, her hand lifted high in exhortation, and the date. These were minted in .903 silver from 1910 to 1914. Between 1917 and 1919, the gold coinage was expanded to include 2, 2½ and 20-peso coins. However, circulation issues of gold ceased in 1921. In 1918, the peso coin was debased, bringing it into line with new silver 10, 20 and 50 centavos coins. All were minted in .800 fineness to a standard of 14.5 g to the peso. The liberty cap design, already on the other silver coins, was applied to the peso. Another debasement in 1920 reduced the fineness to .720 with 12 g of silver to the peso. Bronze 10 and 20 centavos coins were introduced in 1919 and 1920, but coins of those denominations were also minted in silver until 1935 and 1943, respectively.

In 1947, a new issue of silver coins was struck, with the 50 centavos and 1 peso in .500 fineness and a new 5-peso coin in .900 fineness. A portrait of José María Morelos appeared on the 1 peso and this was to remain a feature of the 1-peso coin until its demise. The silver content of this series was 5.4 g to the peso. This was reduced to 4 g in 1950, when .300 fineness 25 and 50-centavo and 1-peso coins were minted alongside .720 fineness 5 pesos. A new portrait of Morelos appeared on the 1 peso, with Cuauhtemoc on the 50 centavos and Miguel Hidalgo on the 5 pesos. No reference was made to the silver content except on the 5 pesos. During this period 5 peso, and to a lesser extent, 10 peso, coins were also used as vehicles for occasional commemorative strikings. In 1955, bronze 50 centavos were introduced, along with smaller 5-peso coins and a new 10-peso coin. In 1957, new 1-peso coins were issued in .100 silver. This series contained 1.6 g of silver per peso. A special 1 peso was minted in 1957 to commemorate Benito Juárez and the constitution of 1857. These were the last silver pesos. The 5-peso coin now weighed 18 grams and was still 0.720 silver; the 10-peso coin weighed 28 grams and was in 0.900 silver. Between 1960 and 1971, a new coinage was introduced, consisting of brass 1 and 5 centavos, cupro-nickel 10, 25 and 50 centavos, 1, 5 and 10 pesos and silver 25 pesos (only issued 1972). In 1977, silver 100 pesos were issued for circulation. In 1980, smaller 5-peso coins were introduced alongside 20 pesos and (from 1982) 50 pesos in cupro-nickel. Between 1978 and 1982, the sizes of the coins for 20 centavos and above were reduced. Base metal 100, 200, 500, 1000 and 5000-peso coins were introduced between 1984 and 1988.

Nuevo Peso

As noted above, the nuevo peso (new peso) was the result of hyperinflation in Mexico. In 1993, President Carlos Salinas de Gortari stripped three zeros from the peso, creating a parity of $1 New Peso for $1000 of the old ones. The transition was done both by having the people trade in their old notes, and by removing the old notes from circulation at the banks, over a period of three years from January 1, 1993 to January 1, 1996. At that time, the word “nuevo” was removed from all new currency being printed and the “nuevo” notes were retired from circulation, thus returning the currency and the notes to be denominated just “peso” again. Confusion was avoided by making the “nuevo peso” currency almost identical to the old “peso”. Both of them circulated at the same time, while all currency that only said “peso” was removed from circulation. The Banco de México (Bank of Mexico) then issued new currency with new graphics, also under the “nuevo peso”. These were followed in due course by the current, almost identical, “peso” currency without the word “nuevo”.

In 1993, coins of the new currency (dated 1992) were issued in denominations of 5, 10, 20 and 50 centavos, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 nuevos pesos. The 5 and 10 centavos were minted in stainless steel and the 20 and 50 centavos in aluminum bronze. The nuevo peso denominations were bimetallic, with the 1, 2 and 5 nuevos pesos having aluminum bronze centers and stainless steel rings, and the 10, 20 and 50 nuevos pesos having .925 silver centers and aluminum bronze rings. In 1996, the word nuevo(s) was removed from the coins. New 10 pesos were introduced with base metal replacing the silver center. The 20, 50, and 100-peso coins are the only currently circulating coinage in the world to contain any silver.

In 2003 the Banco de Mexico began the gradual launch of a new series of bimetallic $100 coins. These number 32 – one for each of the nation’s 31 states, plus the Federal District. While the obverse of these coins bears the traditional coat of arms of Mexico, their reverses show the individual coats of arms of the component states. The first states to be celebrated in this fashion were Zacatecas, Yucatán, Veracruz, and Tlaxcala. In circulation they are extraordinarily rare, but their novelty value offsets the unease most users feel at having such a large amount of money in a single coin. Although the Bank has tried to encourage users to collect full sets of these coins, issuing special display folders for the purpose, the high cost involved has worked against them. Bullion versions of these coins are also available, with the outer ring made of gold, instead of aluminum bronze.

The coins commonly encountered in circulation have face values of 50¢, $1, $2, $5, and $10. The 5¢, 10¢ and 20¢ coins are uncommon due to their small value. Small commodities are priced in multiples of 10¢, but stores may choose to round the total prices to 50¢. There is also a trend for supermarkets to ask customers to round up the total to the nearest 50¢ or 1 peso to automatically donate the difference to charities. The $20, $50 and $100 coins are rarely seen in circulation due to the wide use of the lighter banknotes of the same denominations.

History – First peso

The first banknotes issued by the Mexican state were produced in 1823 by Emperor Iturbide in denominations of 1, 2 and 10 pesos. Similar issues were made by the republican government later the same year. Ten-peso notes were also issued by Emperor Maximilian in 1866 but, until the 1920s, banknote production lay entirely in the hands of private banks and local authorities. In 1920, the Monetary Commission (Comisión Monetaria) issued 50-centavo and 1-peso note whilst the Bank of Mexico issued 2-peso notes. From 1925, the Bank issued notes for 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos, with 500 and 1000 pesos following in 1931. From 1935, the Bank also issued 1-peso notes and, from 1943, 10,000 pesos. Production of 1-peso notes ceased in 1970, followed by 5 pesos in 1972, 10 and 20 pesos in 1977, 50 pesos in 1984, 100 pesos in 1985, 500 pesos in 1987 and 1,000 pesos in 1988. 5,000-peso notes were introduced in 1981, followed by 2,000 pesos in 1983, 20,000 pesos in 1985, 50,000 pesos in 1986 and 100,000 pesos in 1988.

Series A

| · Value | · Obverse | · Reverse |

| · $ 2000 | · Justo Sierra | · Universidad Siglo XIX |

| · $ 5000 | · Niños Héroes | · Castillo de Chapultepec |

| · $ 10000 | · Lázaro Cárdenas | · Hallazgos del Templo Mayor |

| · 20.000 pesos | · Andrés Quintana Roo | · Mural de Bonampak |

| · $ 50,000 | · Cuauhtémoc | |

| · 100.000 pesos | · Plutarco Elías Calles | |

Series B

In 1993, notes were introduced in the new currency for 10, 20, 50, and 100 nuevos pesos. These notes are designated series B by the Bank. (It is important to note that this series designation is not the 1 or 2 letter series label printed on the banknotes themselves.) All were printed with the date July 31, 1992. The designs were carried over from the corresponding notes of the old peso.

Series C and D

In October 1994, Series C was issued with brand new designs. The word “nuevos” remained and 500 nuevos pesos were added. All were printed with the date December 10, 1993. The next series of banknotes, designated series D, was introduced in 1996. It is a modified version of series C with the word “nuevos” dropped, the bank title changed from “El Banco de México” to “Banco de México” and the clause “pagará a la vista al portador” removed. There are several printed dates for each denomination. In 2000, a commemorative series was issued which was like series D except for the additional text “75 aniversario 1925-2000” under the bank title. It refers to the 75th anniversary of the Bank. While series D includes the $10 note and is still legal tender, they are no longer printed, seldom seen, and the coin is more common $10 notes are rarely found in circulation.

Starting from 2001, each denomination in the series was upgraded gradually. On October 15, 2001, in an effort to combat counterfeiting, Series D notes of 50 pesos and above were further modified with the addition of an iridescent strip. On notes of 100 pesos and above, the denomination is printed in color-shifting ink in the top right corner. On September 30, 2002 a new $20 note was introduced. The new $20 is printed on longer-lasting polymer plastic rather than paper. A new $1000 note was issued on November 15, 2004. The Bank of Mexico refers to the $20, $50, and $1000 notes during this wave of change as “series D1”. On April 5, 2004 the Chamber of Deputies approved a measure to demand that the Banco de México produce by January 1, 2006 notes and coins that are identifiable by the blind population (estimated at more than 750,000 visually impaired citizens, including 250,000 that are completely blind). On December 19, 2005, $100, $200, and $500 MXN banknotes include raised, tactile patterns (like Braille), meant to make them distinguishable for people with vision incapacities. This system has been questioned and many demand that it be replaced by actual Braille so it can be used by foreigners not used to these symbols. The Banco de México, however, says they will continue issuing the symbol bills.

The raised, tactile patterns are as follows:

| Value | Bill | Description of pattern |

| $100 | Five diagonal lines side by side, with a negative slope, each broken up into three segments. | |

| $200 | Small broken-up square pattern. | |

| $500 | Four horizontal lines under each other, each broken up into three segments. |

Series F

In September 2006, it was announced that a new family of banknotes would be launched gradually. The 50-peso denomination in polymer was launched in November 2006. The 20-peso note was launched in August 2007. The 1,000-peso note was launched in March 2008. The $200 was issued in 2008, and the $100 and $500 notes were released in August 2010. This family is the F Series. A revised $50 note, with improved security features was released on May 6, 2013. This note is part of the F Series family of banknotes issued by the Banco de Mexico (as Type F1).

Commemorative Bills

On September 29, 2009, The Bank of Mexico unveiled its Commemorative Banknotes. The 100-peso denomination bill commemorates the centennial of the Beginning of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). The 200-peso denomination bill commemorates the bicentennial of the start of the Mexican War for Independence which began in 1810.

- 100 Peso Banknote: Printed on polymer with the dimensions of 66 mm in length, and 134 mm in width. The front of the banknote depicts a locomotive, which was used to transport revolutionary troops, this symbolizes the armed movement that began in 1910. In the reverse side of the banknote there is a segment a mural titled “Del Porfirismo a la Revolución” (From the Dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz to the Revolution), also known as, “La Revolución contra la dictadura Porfiriana” (The Revolution against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz), which was painted by artist David Alfaro Siqueiros. The Bank of Mexico printed 50 million 100-peso banknotes.

There was a printing error in these banknotes, in the small letters (almost unnoticeable, as they are very small and the same color as the waving lines), near the top right corner, just above the transparent corn, from the side of the “La Revolución contra la dictadura Porfiriana”, it is written: “Sufragio electivo y no reelección” (Elective suffrage and no reelection), this supposed to be a quote to Francisco I. Madero’s famous phrase, but he said “Sufragio efectivo no reelección” (Valid Suffrage, No Reelection). The President Felipe Calderón made a newspaper announcement in which he apologized for this, and said that the notes were going to continue in circulation, and that they would retain their value.

200 Peso Banknote: The 200-peso denomination bill commemorates the bicentennial of the Beginning of the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821). This paper banknote is printed in a vertical orientation with dimensions of 66 mm in length and 141 mm in width. The obverse of the banknote depicts the Mexican Leader of Independence, Don Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, carrying his banner that was later used by the independence fighters. The reverse depicts the iconic monument the “Ángel de la Independencia” which is located in Mexico City on the Paseo de la Reforma.

International use

Some establishments in border areas of the United States accept pesos as currency, such as certain border Walmart stores, certain border gas stations such as Circle K, the La Bodega supermarkets in San Ysidro on the Tijuana border. In 2007, Pizza Patrón, a chain of pizza restaurants in the southwestern part of the U.S., started to accept the currency which has been a controversial topic in the United States. Other than in U.S., Guatemalan, and Belizean border towns, pesos are generally not accepted as currency outside Mexico.