November 27, 2015 – Season 7, 30 Tours for Baja Amigos, 25 for Dan & Lisa and here we sit in La Paz off schedule waiting out Hurricane (now Tropical Storm Sandra) to make landfall at the near the south end of the Baja peninsula. I will talk more about that later.

Our time in Loreto was excellent. The weather was warm, RV Park quite (except for the roosters & dogs), as only a couple of other campers arrived there during our 3 day stay in the birthplace of the Californias. Our excursion to San Javier is always interesting, some maintenance and repair was on going, a little more damage in a couple of more sections. Oddly San Javier closed, Mission and compound locked up tighter than a prison (not one Chapo stays in). The Baja Fiesta Dinner at Marvin & Shel’s a hit Roy & Angela, Jeff & Paul, joined the party and dinner, always good to see them again. Martin & Miguel were excellent as always and played for over an hour. Later the gang went to see Jeff & Paul’s place and 2015 Air Stream the purchased, turns out Jeff and Ken grew up close together in the US. As they say it is a small world indeed. On the last day we went for dinner at Ubaldo’s Giggling Dolphin, and introduced Jim & Deb, Wagon-Masters in training.

The journey continued to Palapa 206 with another Stunning drive on the Sea of Cortez and over the mountain range. Only Bertha at Motel, Mike & Nigel at race in Ensenada, Paclo with uncle. However we did have another 3 RVs join us for the night. It was hot and humid for the Happy Hour and I was alerted to Tropical Storm Rick out in the Pacific. We were next headed to the beach and did not want any surprises.

Playa Tecolote was very quiet on arrival, warm 32c for a Sunday, some folks did arrive however they were all gone by sunset. The forecast for showers in afternoon, and rain on Monday, did not happen, Tropical Storm Rick was very late in season, 600 km in Pacific off Baja was confounding weather people. Jim. Deb, Ken and Kathie went out to swim with sea lions, all reports, $650 pesos per person, all reports were everyone had a wonderful time. The group scheduled the the pot luck dinner for the 3rd night to cap off our 3 days on the beach. Lots of swimming, unfortunately not much else as seas were not calm. Of course when we departed south on Wednesday am, calm seas almost like glass.

Playa Tecolote was very quiet on arrival, warm 32c for a Sunday, some folks did arrive however they were all gone by sunset. The forecast for showers in afternoon, and rain on Monday, did not happen, Tropical Storm Rick was very late in season, 600 km in Pacific off Baja was confounding weather people. Jim. Deb, Ken and Kathie went out to swim with sea lions, all reports, $650 pesos per person, all reports were everyone had a wonderful time. The group scheduled the the pot luck dinner for the 3rd night to cap off our 3 days on the beach. Lots of swimming, unfortunately not much else as seas were not calm. Of course when we departed south on Wednesday am, calm seas almost like glass.

Next stop Rancho Verde RV Haven at KM 142 on Hwy 1. Having only 4 RVs the drive was quick arriving at our El Triunfo brunch stop before 10:30 am. There was an Ad being shot in front of El Triunfo Café, lots of pretty girls and good food to enjoy. Headed to Rancho Verde at 1pm and shortly after arrival learned about Hurricane Sandra from Armenia who manages the property.

The general forecast was Sandra was to diminish significantly, lots of rain, wind and some lightning with stronger effects in Cabo than northerly locations. A couple of interesting facts:

- Sandra is the strongest hurricane so late in the season. Only three other eastern Pacific storms have formed later in the calendar than Sandra in records dating to 1949.

- Hurricane Sandra became the second latest forming hurricane on record, behind Hurricane Winnie in 1983.

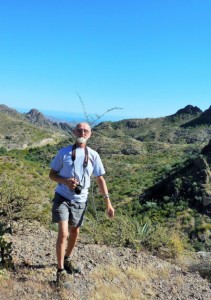

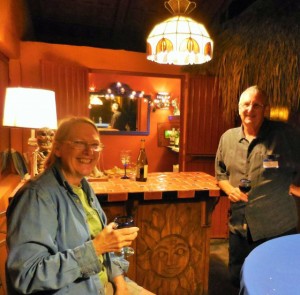

I was on the web late into the evening checking various weather sites and again at 5:30 am the next day prior to our departure south to Cabo San Lucas. Everything I read consistently showed that the effects of Sandra would be half or less in La Paz than Cabo San Lucas. Lisa and I decided to head back to La Paz and sit out Sandra at Campestra Maranatha. We had planned to drop off Allan & Debbie at Los Barilles heading to Cabo. As we were now heading north we invited them to join us in La Paz. They declined and we said our goodbyes, they had a 25 minute drive ahead of them and were anxious to get settled in. At one point Sandra grew to a Category 4 Hurricane and the at 2PM MST yesterday, Thursday, November 26, the Government of Mexico issued a Tropical Storm Watch for the southern portion of the Baja California peninsula from Todos Santos to Los Barriles for approaching Hurricane Sandra. A Tropical Storm Watch means that tropical storm conditions are possible within the watch area, in this case within 36 hours. Not sure how this will turn out, lots of rain and wind for sure. Today we did get to Ibarra’s Pottery and saw Vicki and her Mom, ventured to my favourite La Paz overlook, also sent some time downtown. Later we went to celebrate the US Thanksgiving at a Restaurant in El Centenario.

By Sunday we are forecast to see sunny skies as we continue our trek southbound.

Did you know?

The Log from the Sea of Cortez is an English-language book written by American author John Steinbeck and published in 1951. It details a six-week (March 11 – April 20) marine specimen-collecting boat expedition he made in 1940 at various sites in the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortez), with his friend, the marine biologist Ed Ricketts. It is regarded as one of Steinbeck’s most important works of non-fiction chiefly because of the involvement of Ricketts, who shaped Steinbeck’s thinking and provided the prototype for many of the pivotal characters in his fiction, and the insights it gives into the philosophies of the two men.

The Log from the Sea of Cortez is the narrative portion of an unsuccessful earlier work, Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research, which was published by Steinbeck and Ricketts shortly after their return from the Gulf of California, and combined the journals of the collecting expedition, reworked by Steinbeck, with Ricketts’ species catalogue. After Ricketts’ death in 1948, Steinbeck dropped the species catalogue from the earlier work and republished it with a eulogy to his friend added as a foreword.

History

Steinbeck met Ricketts in 1930 through a shared interest in marine biology. Ricketts made a modest living as a professional biologist by preparing and selling specimens of intertidal fauna to laboratories and universities from his small lab in Cannery Row, and Steinbeck spent many hours at the lab in Ricketts’ company. Ricketts was the inspiration for the boozy, good-hearted character of “Doc”, who appeared in the novels Steinbeck set in and around Monterey, and elements of his personality are mirrored by many other important characters in Steinbeck’s novels.

Both Steinbeck and Ricketts had achieved some measure of security and recognition in their professions by 1939: Steinbeck had capitalized on his first successful novel, Tortilla Flat, with the publication of The Grapes of Wrath, and Ricketts had published Between Pacific Tides, which became the definitive handbook for the study of the intertidal fauna of the Pacific Coast of the coterminous United States. Steinbeck was exhausted and looking for a new start; Ricketts was looking for a new challenge. The two men had long thought of producing a book together and, in a change of pace for both of them, they began work on a handbook of the common intertidal species of the San Francisco Bay Area. The book came to nothing, but it spurred them into making a trip to the Sea of Cortez. Initially they planned a motoring trip to Mexico City as a break from their work on the handbook, but as time went on they became more interested in a collecting trip around the Gulf of California. Ricketts noted in his journal:

Jon said, “If you have an objective, like collecting specimens, it puts so much more direction onto a trip, makes it more interesting.”…Then he said, “We’ll do a book about it that’ll more than pay the expenses of the trip.”

A specimen-collecting expedition along the Pacific Coast and down into Mexico provided them with a chance to relax, and, for Steinbeck, a chance for a brief escape from the controversy mounting around The Grapes of Wrath. Ricketts, suffering as a result of the breakup of his long-term relationship with a married woman in Monterey, was glad to get away too. They planned to collect specimens from the rock and tide pools and the shore line uncovered between tides which would allow them build up a picture of the macro level ecosystem in the Gulf. The preserved specimens of the fauna they collected could be identified and catalogued or sold on their return.

Early in 1940, Steinbeck and Ricketts hired a Monterey Bay sardine fishing boat, the Western Flyer, with a four-man crew, and spent six weeks travelling the coast of the Gulf of California collecting biological specimens. Along with Ricketts and the four crew members mentioned in the book, Steinbeck was accompanied by his wife, Carol. Steinbeck hoped that the trip would help rescue their failing marriage, but it seems to have had the opposite effect: the marriage ended soon after they returned. Steinbeck’s lawyer and friend, Toby Street, was also on board as far as San Diego.

The expedition

The Western Flyer was a 75-foot (23 m) purse seiner, crewed by Tony Berry, the captain; “Tex” Travis, the engineer; and two able seamen, “Sparky” Enea and “Tiny” Colletto. Stocked with supplies, collecting equipment and a small library, the boat put out to sea on the afternoon of March 11, 1940. They started in a leisurely fashion down the Pacific coast, fishing as they went. They refueled at San Diego and on March 17 passed Point San Lazaro and made their way down the Pacific side of the Baja California peninsula. They put in at Cabo San Lucas, on the tip of the peninsula, where they were greeted by Mexican officials and began collecting specimens. The collecting team was initially planned to consist of Steinbeck and Ricketts alone, but Carol and eventually Enea and Colletto joined them, allowing for a much more efficient collection at each stop.

The battles with their outboard motor, referred to pseudonymously as the “Hansen Sea-Cow”, which would feature as a humorous thread throughout the journal, began immediately and continued the next day when they moved further round the coast to El Pulmo Reef. Making for Isla Espiritu Santo they faced strong winds and, rather than attempting to land at the island, they anchored at Pescadero on the mainland. On March 20 they returned to the island and spent the day collecting. A visit from some natives of La Paz that evening, coupled with the exhaustion of their supplies of beer, encouraged them to make for the town the next morning. They spent three days collecting with the assistance of the locals, and enjoyed the hospitality of La Paz. In writing about the town, Steinbeck briefly recounts the story that he would later rewrite as The Pearl.

On March 23, they moved on to San José Island, where the “Sea-Cow” again let them down: they wanted it to bring the boat close to Cayo islet, but they ended up rowing the boat, with the outboard still attached, after it failed to start. The next day, Easter Sunday, they continued on to Marcial Reef. After collecting specimens there, they sailed to Puerto Escondido where they met some holidaying Mexicans who invited them on a hunting trip. They accepted, wanting to see the interior of the peninsula, and enjoyed two days in the company of the Mexicans, eating, drinking and listening to unintelligible dirty jokes in Spanish. Due to the relaxed attitudes of their hosts, no actual hunting took place, which pleased Steinbeck.

On March 23, they moved on to San José Island, where the “Sea-Cow” again let them down: they wanted it to bring the boat close to Cayo islet, but they ended up rowing the boat, with the outboard still attached, after it failed to start. The next day, Easter Sunday, they continued on to Marcial Reef. After collecting specimens there, they sailed to Puerto Escondido where they met some holidaying Mexicans who invited them on a hunting trip. They accepted, wanting to see the interior of the peninsula, and enjoyed two days in the company of the Mexicans, eating, drinking and listening to unintelligible dirty jokes in Spanish. Due to the relaxed attitudes of their hosts, no actual hunting took place, which pleased Steinbeck.

Puerto Escondido proved to be a rich collecting ground, and after nine days in the Gulf, they had to scale back their collecting ambitions owing to lack of space for the specimens. It had already become clear that there were certain species that were ubiquitous in the region: some species of crabs, sea anemones, limpets, barnacles and sea cucumbers were found at every stop, and the sun star, Heliaster kubiniji, the sea urchin, Arbacia incisa, and bristleworms of the Eurythoe genus were common.

Leaving Puerto Escondido, they continued up the coast to Loreto, where they restocked their supplies. They then visited the Coronado Islands, Concepcíon Bay and San Lucas Cove, collecting specimens at each stop. The work was exhausting; Steinbeck wrote in his letters that he had little time for sleep because the collecting and preparation took so long. In the cramped quarters of the boat, all the equipment had to be set up and stowed each time the boat moved to a new anchorage, which made the work of cataloguing and processing the specimens doubly arduous. Making their way to San Carlos Bay, they bypassed the town of Santa Rosalía, and entered the sparsely populated upper Gulf, stopping at San Francisquito Bay. On April 1, they made for Bahía de los Ángeles, which was to be the last stop on the peninsula before they crossed to the mainland coast. On April 2 they rounded Isla Ángel de la Guarda, and anchored in Puerto Refugio for the night. The next morning they made for Tiburón Island, on the eastern side of the Gulf. They collected specimens at Red Point Bluff, keeping an eye out for the Seri, a local tribe who they had heard were rumored to be cannibals.

Although the crew were eager to get to Guaymas as soon as possible, it was too far for a single day’s journey, so the next day they put in at Puerto San Carlos, where they collected. Early the next morning they made the short run to Guaymas. They left Guaymas on the morning of April 8 and, only an hour out, encountered a Japanese fishing fleet dredging the bottom. Although initially wary, the crew of one of the boats welcomed Steinbeck and Ricketts on board and allowed them to select some specimens from the catch, though to the annoyance of the crew of the Western Flyer, Ricketts and Steinbeck forgot to get any fish to eat. Taking leave of the fleet, they made for the Estero de la Luna, a huge estuary where Ricketts and Steinbeck became lost in fog while out on a collecting expedition, after the “Sea-Cow” once again refused to run. Although spooked by the episode, they were able to navigate back to the Western Flyer once the fog cleared.

Continuing down to Agiabampo lagoon, they stopped to collect along the shores, and then recrossed the Gulf by night, putting in at San Gabriel Bay for a last collection before making for home. On the afternoon of April 12 they secured all the equipment and laid in a course for San Diego. The collecting trip had been very successful: they catalogued over 500 species of the fauna of the shores of the Gulf; recorded a species of brittle star, Ophiophragmus marginatus, last recorded nearly 100 years earlier; and discovered about 50 new species. Three species of sea anemone they discovered were named for them by Dr. Oscar Calgren at the Lund University’s Department of Zoology in Sweden: Palythoa rickettsii, Isometridium rickettsi, and Phialoba steinbecki.

The Book -Sea of Cortez

The year after their return from the trip Steinbeck and Ricketts published Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research, in which Steinbeck combined the daily journals of the trip with Ricketts’ annotated specimen list. The title “Sea of Cortez” was preferred to the “Gulf of California” as a better-sounding and a more exciting name. It was assumed by many that Steinbeck had kept a journal during the trip and that the book was merely an amalgamation of his log and Ricketts’ taxonomic list; but the two authors revealed that the journal was Ricketts’. Although Steinbeck had added to it during the journey, he had done the real work of editing it after they returned. The log was based on what Ricketts called the Verbatim Transcript, an account of the trip he had compiled from the various notes he kept during the trip. Much of the final narrative was little changed from Ricketts’ notes; Steinbeck shifted from the first person singular to the first person plural and gave some of Ricketts’ drier prose a poetic twist, but many of the scenes remained almost unchanged from the daily journal. The suggestion by Steinbeck’s editor, Pascal Covici, that the title page should state that Steinbeck was the author and add that the appendices were by Ricketts met with blunt opposition from Steinbeck: “I not only disapprove of your plan — I forbid it”. Steinbeck also drew upon the journal of Tony Berry, mostly to confirm dates and times.

The book is a travelogue and biological record, but also reveals the two men’s philosophies: it dwells on the place of humans in the environment, the interconnection between single organisms and the larger ecosystem, and the themes of leaving and returning home. A number of ecological concerns, rare in 1940, are voiced, such as an imagined but horrific vision of the long term damage that the Japanese bottom fishing trawlers are doing to the sea bed. Although written as if it were the journal kept by Steinbeck during the voyage, the book is to some extent a work of fiction: the journals are not Steinbeck’s, and his wife, who had accompanied him on the trip, is not mentioned (though at one point Steinbeck slips and mentions the matter of food for seven people). Since returning home is a theme throughout the narrative, the inclusion of his wife, a symbol of home, would have dissipated the effect. Steinbeck and Ricketts are never mentioned by name but are amalgamated into the first person “we” who narrate the log.

Sea of Cortez-Reboot

Ricketts was killed in 1948 when a train collided with his car while he was crossing the rail tracks. Ricketts’ death severely hurt Steinbeck: “he was part of my brain for 18 years”. Although Steinbeck had moved to New York shortly after the journey and the two men had not seen as much of each other in the following years, they had corresponded by mail and had been planning a further expedition, this time northwards to the Aleutian Islands. In 1951 Steinbeck republished the narrative portion of Sea of Cortez as The Log from the Sea of Cortez, dropping Ricketts’ species list and adding a preface entitled “About Ed Ricketts”, a biography of his friend.

Pascal Covici had always regarded Ricketts as a hanger-on and had been keen to deny his authorship of the original book. He pushed Steinbeck to get Ricketts’ son, Ed Jr., to sign over the copyright to the narrative portion of the book, so that the reissued version could credit Steinbeck alone. Covici suggested a 15–20% share of the royalties as a recompense; but Ed Jr., knowing that the narrative was largely Ricketts’ own, insisted on 25%. With the copyright secured, Ricketts’ name was dropped from the cover, though the title page acknowledged that the book was “the narrative portion of the Sea of Cortez by John Steinbeck and E.F. Ricketts”, and throughout his life, Steinbeck insisted on referring to the work as a collaboration. The republished narrative is unchanged from the original published in Sea of Cortez.

The republished version enjoyed greater success than the original. Although, by the time of his death in 1968, Steinbeck’s reputation was at an all-time low owing to his mediocre output during the last decades of his life and his support for American involvement in Vietnam, his books have slowly regained their popularity. The Log from the Sea of Cortez became an important work within his oeuvre, not only as an interesting travelogue and work of non-fiction, but for its first-hand account of Ed Ricketts, the man whose thinking had so much influence on the course of Steinbeck’s writing and on whom he had based so many of his pivotal characters. Whereas earlier critics mostly assumed that “Mr. Ricketts contributed some of the biology, and Mr. Steinbeck all of the prose”, the publication of Ricketts’ rediscovered original notes in 2003 has revealed how closely Steinbeck followed Ricketts’ journal. This has forced a re-evaluation of how far it is fair to attribute authorship of the narrative portion of Sea of Cortez to Steinbeck, and has caused critics to view the removal of Ricketts’ name from the cover as reflecting badly on Steinbeck.

Travels With Charley: In Search of America, another non-fiction travelogue which Steinbeck wrote in 1962, is seen as a more rounded view of the author late in life, but The Log from the Sea of Cortez is regarded as showing the direct influence of Ed Ricketts and his philosophies on Steinbeck, and provides clues to the underlying rationales for some events in his novels. In particular, “About Ed Ricketts” reveals how closely he was tied to the characters in Steinbeck’s novels: parts are taken almost verbatim from descriptions of “Doc” in Cannery Row. The book is also important for seeing something of Ed Ricketts himself. It was the only example of his philosophical writings published in his lifetime. The “Essay on Non-teleological Thinking” was part of a trilogy of philosophical essays he had written before the trip, and which, with Steinbeck’s help, he continued to try to have published until his death. As a travelogue it captures a lost world. Even as they were making the trip, a new hotel was being built in La Paz. Steinbeck bemoaned the coming of tourism:

“Probably the airplanes will bring week-enders from Los Angeles before long, and the beautiful poor bedraggled old town will bloom with a Floridian ugliness,” Steinbeck said.

Today, Cabo San Lucas is home to luxury hotels and the houses of American rock stars, and many of the small villages have become suburbs of the larger towns of the Gulf, but people still visit, attempting to capture something of the spirit of the leisurely journey Steinbeck and Ricketts took around the Sea of Cortez.