January 13, 2015 – After leaving Playa Santispac on schedule and before you knew it we had arrived in Loreto without incident after one of my favourite drives from Bahia Concepcion to California’s original capital. After we got settled we went on a short excursion around town, the bank and picked up a few groceries. Later some folks went out to dinner, Orlando’s is one of our favourites. Tomorrow we are off for San Javier then our Fiesta Night Dinner at the Giggling Dolphin, this is always a hi-light if the tour.

We have been on the road now few days now since my last Blog from Punta Banda, and on Day 2 our drive to Fidel’s El Pabellon Palapas Alvinos at KM 60 south of Lazaro Cardenas was unusually quiet, really not much traffic, which was good. The road was firm as it hadn’t rained for some time, as we know it can be muddy and a real mess. Everyone found just the right spot for themselves and spent time exploring the beach. Fidel provided some great firewood and the hot dog roast was a success, this has become a good icebreaker for the group. Mike was able to try out his drone without having to worry about trees and that kept Jitterbug calm hiding in the trailer, maybe we should get one? Met a number of other BC Snowbirds also heading south at Fidel’s, including Greg and Debbie who we have met several times before, some we will see again at Santa Ines and Malarrmo in Guerrero Negro.

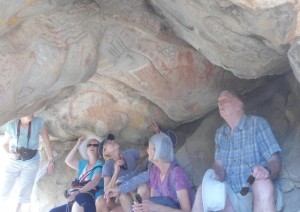

The next day we were off to Catavina, again the roads had much less traffic on them then we had anticipated, perhaps the high cost of fuel is keeping the locals off the highway, not sure. Before getting to the Onyx Café where Luis & Lisa are raising their kids, we encountered a bad accident, sadly a fatality, someone passing around a corner on a hill. Fortunately a 2 Km side unpaved road was available and the police were redirecting all the traffic onto it. It was much better than most of the lateral construction roads we have been on lately. We pulled into Santa Ines around lunch time and were off to our Cave Painting excursion after lunch. Including us I counted 13 RVers and tent campers at the campground, the numbers of folks on Baja do seem to be up this January. A quiet night at Catavina except for some serenading coyotes in the early hours.

Day 4 and we off to Guerrero Negro and Baja Sur, again thankfully traffic was light, this time we did not encounter any road accidents. We set up at Malarrimo Hotel, Restaurant and Trailer Park then off to Tony’s Tacos (El Muelle), arguably the best on Baja just 3 blocks down the main drag. Another short walk and we were at the Grocery Store picking up a few items for the beach Pot Luck in a couple of days. Dinner at Malarrimo’s was Fabuloso, many had the Seafood platter. I had a New York steak and Lisa had Yellowtail, no disappointment in either. The next morning at 8:00 AM most of the gang headed out to see the Grey Whales, well over a hundred in Scammon’s Lagoon with 20-30 arriving each day now to birth and breed. They had a delayed start because of the fog but eventually departed and had a wonderful encounter with the Eschrichtius robustus (Grey Whales).

On the group’s return we packed up and headed off to San Ignacio, a date palm oasis located between Guerrero Negro and Santa Rosalia with a modest population of about 4,000. The village was originally home to a Cochimi settlement of Kadakaaman with a Jesuit Mission San Ignacio founded in 1728 by Juan Bautista Luyando. After set up at Rice & Beans Hotel and RV Park we headed into town see the San Ignacio Mission, fully restored in 1976, the lagoon and beautiful Zocolo lined with 300 year old Fig trees from India brought by the Dominican missionary’s. Most joined us for dinner back at the park and many tasted the famous Margaritas, arguably the best on Baja. Ricardo always does a good job with dinner, most had the Mexican plate, Lisa had a chicken enchilada, myself Carne Asada, all simply delicious.

Our departure was scheduled for 8:00 am however the group was keen to depart so we headed off a few minutes early to Playa Santispac south of Mulege. Our drive to Santa Rosalia went very smoothly, again little traffic. The view of the Sea of Cortez from the plateau before our decent on the Cuesta del Inferno to Santa Rosalia is always stunning, as we got closer we could see the ocean was clam. On this tour we stopped at the PEMEX on the way into town for our fuel up and they had no problems making change. We arrived at the beach about 11:30 am to calm seas which remained so for our entire stay. On the day we arrived we hit 30C in the shade and almost the same the 2nd day, with no wind until the afternoon of day 2 on the beach. It was great to see our friends Gary & Linda, Gord & Kathy, George and of course Bruce & Marian. Almost everyone took the opportunity to try the paddle board or kayak and we had many dolphins in the bay, a real treat for sure. Bruce & Marian provided the firewood for our potluck dinner and took me out earlier in the day for a boat tour of some of the local beaches, something I had never done before. We saw many Dolphins out on the water, one jumped clear out of the water beside the boat, later we came across a large Stellar Sea Lion basking in the sun on his back, and we were able to get quite close for some good photos. Daniel & Lise moved their Van to block the wind for our Potluck dinner and we had a real variety of wonderful dishes for what turned out to be a real feast. Afterwards we put that firewood to good use to warm everyone up, the wind faded and this was another Baja experience that folks will remember for years to come.

Did you know?

The Institutional Revolutionary Party (Spanish: Partido Revolucionario Institucional, PRI) is a Mexican political party that held power in the country for 71 years, first as the National Revolutionary Party, then as the Party of the Mexican Revolution. The PRI is a centrist party member of the Socialist International. However, the PRI is not considered a social democratic party in the traditional sense; its modern policies of neo-liberalism and privatization have been characterized as centrist or even as liberal. Its membership in the Socialist International dates from the Mexican Revolution (1910) and the founding of the party by Plutarco Elías Calles (1929), when the party had a clearer social democratic orientation. Along with their rival, the left-wing PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution), they make Mexico one of the few nations with two major, competing parties part of the same international grouping. The PRI is the largest political party in Mexico, according to numerical observation. The adherents of the PRI party are known in Mexico as priísta and the party is nicknamed el tricolor because of its use of the colors green, white and red.

In terms of power, it was second only to the president, who also serves as the party’s effective chief. Until the early 1980s, the PRI’s position in the Mexican political system was hegemonic, with opposition parties posing little or no threat to its power base or it’s near monopoly of public office. This situation changed during the mid-1980s, as opposition parties of the left and right began to seriously challenge PRI candidates for local, state, and national-level offices. As the National Revolutionary Party (Partido Nacional Revolucionario–PNR), this was a loose confederation of local political bosses and military strongmen grouped together with labor unions, peasant organizations, and regional political parties. In its early years, it served primarily as a means of organizing and containing the political competition among the leaders of the various revolutionary factions. Calles, operating through the party organization, was able to undermine much of the strength of peasant and labor organizations that affiliated with the party and to weaken the regional military commanders who had operated with great autonomy throughout the 1920s. By 1934 Calles was in control of Mexican politics and government, even after he left the presidency, largely through his manipulation of the PNR.

Between 1934 and 1940, an intense struggle for political control developed between Calles and the new president, Lazaro Cárdenas. At the time, Calles represented the conservative elements of the revolutionary coalition, while Cárdenas drew his support from the more radical political elements. To strengthen his hand against Calles, Cárdenas reunited the labor and peasant organizations that Calles had earlier fragmented and formed two national federations, the National Peasant Confederation (Confederación Nacional Campesina–CNC) and the Confederation of Mexican Workers (Confederación de Trabajadores Mexicanos–CTM). Using these organizations as the bases of his support, Cárdenas then reorganized the PNR in 1938, renaming it the Party of the Mexican Revolution (Partido de la Revolución Mexicana–PRM), incorporating the CTM and the CNC and giving the PRM an organization by sectors: labor, agrarian, popular, and military. The creation of these groups and their integration into the party marked the legitimation of the existing interest group organizations and the transformation of the political system from an elite to a mass-based system. Within a year, the PRM claimed some 4.3 million members: 2.5 million peasants, 1.3 million workers, and 500,000 in the popular sector. In 1946 President Manuel Ávila Camacho abolished the military sector, shifted its members into the popular sector, and renamed the party the PRI.

Beginning with the Cárdenas administration in the late 1930s, the PRI and its predecessors engineered an unprecedented political peace. The overt political intervention by the military that had characterized the country’s politics throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries largely disappeared when Ávila Camacho, the last president who came from a military background, left office in 1946. For nearly five decades, there were few episodes of large-scale organized violence and no revolutionary movements that enjoyed widespread support, despite considerable economic strains between 1968 and 1975 and a difficult period of economic austerity beginning in 1982.

For the middle class, whose members typically had led rebellions in the past, the PRI provided upward mobility either through politics (the rule of no re-election opened frequent opportunities for public office) or through business during the high-growth period of “stabilizing development” that lasted from the early 1950s until the late 1960s. The PRI also integrated workers and peasants into the political system by claiming to be the only vehicle able to realize their demands for labor union rights and land reform. The party operated much like an urban political machine in the United States. It weakened attempts to form horizontal class- or interest-based political alliances within the lower class by dispensing services to individuals in exchange for their votes. The PRI emphasized personal relationships between individuals of the lower class and party and government officials. It distributed political patronage from the top down to members of organized labor, the agrarian movement, and the popular sector in accordance with each group’s relative strength in a given area. Finally, it used electoral fraud, corruption, bribery, and repression when necessary to maintain control over individuals and groups.

From 1929 to 1982, the PRI won every presidential election by well over 70 percent of the vote—unfortunately these margins were usually obtained by massive electoral fraud. Toward the end of his term, the incumbent president in consultation with party leaders, selected the PRI’s candidate in the next election in a procedure known as “the tap of the finger” (Spanish: el dedazo). In essence, given the PRI’s overwhelming dominance, the president chose his successor. The PRI’s dominance was near-absolute at all other levels as well. It held an overwhelming majority in the Chamber of Deputies, as well as every seat in the Senate and every state governorship.

Sadly after several decades in power the PRI had become a symbol of corruption and electoral fraud. Consequently, its left wing went on to form its own party the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) in 1989. The conservative National Action Party (PAN) became a stronger party after 1976 when it obtained the support from businessmen after recurring economic crises. The growth of these two parties culminated in the loss of the presidency in 2000, won by the PAN and again in 2006 (won this time by the PAN with a small margin over the PRD.) Many prominent members of the PAN (Manuel Clouthier, Addy Joaquín Coldwell and Demetrio Sodi), most of the PRD (most notably all three Mexico City mayors Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and Marcelo Ebrard), the PVEM (Jorge González Torres) and New Alliance (Roberto Campa) were once members of the PRI, including many presidential candidates from the opposition (Clouthier, López Obrador, Cárdenas, González Torres, Campa and Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, among many others).

Historically the PRI has been criticized for using the colors of the national flag in its logo, something considered not unreasonable in many countries, but frowned upon in Mexico, while there is no law that forbids this act. Critics claim electoral fraud, with voter suppression and violence, was used when the political machine did not work and elections were just a ritual to simulate the appearance of a democracy. Ironically now, the three major parties now make the same claim against each other (PRD against Vicente Fox’s PAN and PAN vs. López Obrador’s PRD, and the PRI against the PAN at the local level and local elections such as the Yucatán state election, 2007). Two other PRI presidents Miguel de la Madrid and Carlos Salinas de Gortari privatized many outmoded industries, including banks and businesses, entered the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and also negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement. Greater economic stability since the last major economic crisis in Mexico (the 1995 peso crisis) was achieved in great part through economic reforms begun under Ernesto Zedillo, who was the last successive PRI-nominated president to serve since the Mexican Revolution, and whose tenure commenced just as the peso crisis was coming to a head. Subsequent administrations maintained stability with continued assistance from PRI members such as Secretary of Finance Francisco Gil Diaz and Bank of Mexico Governor Guillermo Ortiz.

In 2012 with Enrique Peña Nieto and after ruling for most of the past century in Mexico, the PRI returned to the presidency as it had brought hopes to those who gave the PRI another chance and fear to those who worry about the old PRI tactics of making deals with the cartels in exchange for relative peace. According to an article published by The Economist on June 23, 2012, part of the reason why Peña Nieto and the PRI were voted back to the presidency after a 12-year struggle lies in the disappointment of the ruling of the PAN. Buffeted by China’s economic growth and the economic recession in the United States, the annual growth of Mexico’s economy between 2000 and 2012 was 1.8%. Poverty exacerbated, and without a ruling majority in Congress, the PAN presidents were unable to pass structural reforms, leaving monopolies and Mexico’s educational system unchanged. In 2006, Felipe Calderón chose to make the battle against organized crime the centerpiece of his presidency. Nonetheless, with over 60,000 dead, many Mexican citizens are tired of a fight they had first supported. The Economist alleges that these signs are “not as bad as they look,” since Mexico is more democratic, it enjoys a competitive export market, has a well-run economy despite the crisis, and there are tentative signs that the violence in the country may be plummeting. But if voters want the PRI back, it is because “the alternatives [were] weak”. The newspaper also alleges that Mexico’s preferences should have gone left-wing, but the candidate that represented that movement – Andrés Manuel López Obrador – was seen with “disgraceful behaviour”. The conservative candidate, Josefina Vázquez Mota, was deemed worthy but was considered by The Economist to have carried out a “shambolic campaign”. Thus, Peña Nieto wins by default and was considered by the newspaper as the “least bad choice” for reform in Mexico.

The return of the PRI, however, is not welcomed by everyone. When it was tossed from the presidency in the year 2000, few expected that the “perfect dictatorship”, a description coined by Mario Vargas Llosa, would return again in only 12 years. According to the Statesman Journal, “history books will tell you” that for more than seven decades, the PRI ran Mexico under an “autocratic, endemically corrupt, crony-ridden government”. The elites of the PRI allegedly ruled the police and the judicial system, and justice was only available if purchased with bribes. During its time in power, the PRI became a symbol of corruption, repression, economic mismanagement, and electoral frauds, and many educated Mexicans and urban dwellers worry that its return may signify a return to Mexico’s past. People are also afraid that democracy will no longer exist when the PRI comes to power. Associated Press published an article on July 2012 noting that many immigrants living in the United States are worried about the PRI’s return to power and that it may dissuade many from returning to their homeland. The vast majority of the 400,000 voters outside of Mexico voted against Peña Nieto, and said they were “shocked” that the PRI – which largely convinced them to leave Mexico – has returned. Voters that favor Peña Nieto, however, believed that the PRI “has changed” and that more jobs will be created under the new regime. Moreover, some U.S. officials are concerned that Peña Nieto’s security strategy meant the return to the old and corrupt practices of the PRI regime, where the government made deals and turned a blind eye on the cartels in exchange for peace. After all, they worried that Mexico’s drug war, which has cost over 60,000 lives, would make Mexicans question on why they should “pay the price for a US drug habit”. Peña Nieto denies, however, that his party would tolerate corruption and stated he would not make deals with the cartels.

The abduction and murder of 43 students recently in the state of Guerrero that involved both the local Police and Drug Cartel associates has become a “Trigger” for Mexicans of walks of life to bring an end to this insane human carnage and brought tremendous political pressure on the current President. It will be interesting to see how this all plays out in our beloved Mexico particularly in the context of world oil prices plummeting as PEMEX prices at the pump continue to rise.